Those who’ve read it might remember that the plot of Jane Austen’s Persuasion turns on Mrs Smith: Anne Elliot’s former schoolmate who, widowed after an unfortunate marriage, has fallen on hard times. Mrs Smith’s difficulties are compounded by physical pain: Austen describes her as an “invalid,” who is clearly suffering from what today we’d call arthritis. When Anne visits her friend, she finds her living “in a noisy parlour, and a dark bedroom behind…in a very humble way, unable even to afford herself the comfort of a servant, and of course almost excluded from society.” That “of course” says so much about the position of a nineteenth-century woman like Mrs Smith: her situation means a particular kind of social exile is inevitable. The difficulties of penniless widowhood are compounded by disability, and while her polite education might have fitted her for marriage, it has excluded her from the kind of paid employment a woman of labouring rank might seek.

Anne is surprised to find Mrs Smith both cheery and resilient. After a period of observation, she attributes her friend’s attitude to an “elasticity of mind, that disposition to be comforted, that power of turning readily from evil to good, and of finding employment which carried her out of herself.” The employment that carries Mrs Smith “out of herself” is making, and being paid for the things that she has made. She is able to sell sewn and knitted items through an intermediary, a nurse who, Mrs Smith tells Anne, is “an invaluable acquaintance. As soon as I could use my hands she taught me to knit, which has been a great amusement; and she put me in the way of making these little thread-cases, pincushions and card-racks, which you always find me so busy about.”

Women like Mrs Smith abound in nineteenth-century fiction. Because they are of a certain class, they are excluded from the division of labour, and their only means of any sort of financial independence is through the sale of their own plain or fancy work: an acceptably feminine employment in which all women of virtue might apparently participate (for the grim fate of those whose domestic virtues are questionable, see Lily in Wharton’s House of Mirth). In nineteenth-century novels (and indeed, in nineteenth century reality) these women retain the respectability of their rank by not undertaking the grubby business of buying and selling themselves: remember for example, how important it is that Cranford’s Miss Matty is saved from the fate of the shop by the interposition of her long-absent brother. However dire her financial circumstances, then, a gentlewoman stays a gentlewoman by not being seen to sell stuff for money. Mrs Smith happily has the nurse to do the selling for her, and other women might preserve their anonymity though the mediating actions of charitable institutions like The Royal Edinburgh Repository and Self Aid Society, which still exists today.

Founded in 1882, the Royal Edinburgh Repository and Self-Aid Society was established “to assist those of limited means to achieve an independent livelihood by promoting the sale of their own handiwork.” Originally managed by two New-Town sisters, the Society sold on the work of its indigent members at bazaars whose “tea cosies and Shetland wool cravats,” were satirised by a young and waspish Robert Louis Stevenson. Since 1946, the society has operated from a well-placed shop on Castle Street. Though its general social context has (thankfully) radically changed — making and selling things for money is no longer a source of shame for a woman of any class — in spirit and reality, the society remains remarkably true to its original aims and ethos.

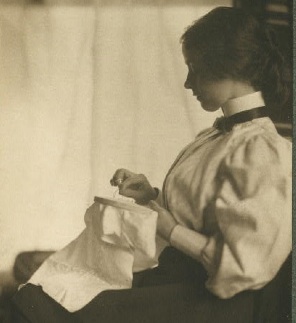

(Mrs Vanderbilt’s charity bazaar)

Today you do not have to be a gentlewoman (or even a woman) to be a society member — but you do have to be of limited means, and be able to knit (or sew, or crochet) to a certain standard (everything sold by the Repository is ‘passed’ for quality by its executive committee). The individual maker sets the price of their work themselves, and to me there is something incredibly contemporary and utopian in the Repository’s support of co-operative enterprise, its celebration of craft and making, and in ensuring that each maker is fairly recompensed.

We were completely blown away The Repository. The shop is known as “the treasure trove” — and this is indeed what it is. We found amazing Fairisle gloves, tams and sweaters: all luminous and intricate, the work of incredibly talented knitters. There are Shetland christening shawls, and wonderful aran sweaters; baby clothes and blokes cardigans; colourwork, cables and lace.

Today, it is often hard to buy hand-knitted items without worrying about the labour practices that produced them. While admirable organisations like Thistle and Broom ensure that craftswomen and men receive two-thirds of the profits of their labour, there are many other less scrupulous organisations in the UK and elsewhere who, in remunerating per finished item rather than time expended, are not only paying knitters poorly but illegally. While I personally feel that the Repository would be well within their rights to charge quite a bit more for the things that they sell, you still know that if you buy a handmade item here, that you are directly supporting the maker.

(gloves made by member no. 66)

So I am now the proud owner of a pair of gloves made by member no. 66. They are beautiful. My only wish is that I might pass on my thanks to knitter 66 directly, but perhaps that anonymity which, a hundred years ago was there to protect the knitter from the taint of the shop counter, now has another function entirely: if I were knitter 66, I probably wouldn’t want to be bothered by the likes of me in full-blown rhapsodic knitting mode.

I am still musing on the fate of Austen’s Mrs Smith, and wondering how the modest financial independence she gained from making might have been rather differently inflected, or perhaps enhanced by the collective and co-operative structure which the Edinburgh Repository provided, and indeed still provides. I feel some research coming on. In the meantime, I urge everyone, whether in or near Edinburgh, or if planning a future visit, to make your way to 23A Castle Street, where you are sure to be inspired.

” I probably wouldn’t want to be bothered by the likes of me in full-blown rhapsodic knitting mode.”

I’ll try not to, but I feel you’ve outdone yourself with this particular entry. The information and cleanness of your style is always a breathe of fresh air for me. And I was just reading Persuasion, though I found myself wondering if Mrs. Smith had suffered from some acute, as opposed to chronic, auto immune illness, but that’s my personal experience coloring my reading. Thanks for so many happy times. The Definitive Craft Tour of Edinburgh sounds like a dream.

LikeLike

I’ve often thought of Mrs. Smith – I love Jane Austen, especially Persuasion – and I identify with her. I clothe, feed and manage my family on my needles (or, rather, through the work of my needles…)

It’s not easy – but it’s not bad – it’s worthwhile and I feel giddily fortunate to be able to do it. But work – in the form of knitting – is a constant in my life in ways it may not be for other knitters.

Thank you for this very considered post. I cannot wait to visit the Royal Repository on my upcoming trip to Edinburgh!

LikeLike

How lovely the things from the repository are! And equally inspiring!

I’m so glad to have found your blog–lovely, lovely!

LikeLike

I’ve been reading your blog for some time now, but I’ve yet to leave a comment. I really adore the things you knit, but I also really appreciate the way you share your professor’s mind with us. It is incredibly unique, the way you blend the two, and I am so grateful to have a place to check into where I know I will both see beautiful things and learn so much. Knitting and Learning are two of my greatest passions and you bring them together so well. Thank you!

LikeLike

http://www.womansindustrialexchange.org/

i thought this ancient institution in baltimore might interest you.

and lily’s dismissal from the hat trade — Miss Bart, if you can’t sew those sequins on any faster I’m afraid we’re going to have to let you go — is my personal nightmare.

LikeLike

Oh, i had completely forgotten about that shop – i used to go into it a lot – i remember that i bought a peg bag for a friend once. the ladies in it are lovely too. I do miss Edinburgh sometimes.

LikeLike

What a great post. Next time I’m in the northern hemisphere I’ll be back in Edinburgh. The Repository looks amazing. It’s on my list, that is if you don’t come up with “The Definitive Craft Tour of Edinburgh” to supersede it. Every city should have one!

LikeLike

It is pleasure to visit your blog. Thank you for your sharing.

LikeLike

What a lovely and informative entry. I often find myself entangled in Victorian literature and have become increasingly interested in the history of knitting (and all textile arts). You’ve added another piece to the mosaic. And yet another reason to dream of visiting Scotland.

LikeLike

A tam seems like an appropriate thing to come home with!

LikeLike

This has stirred a vague memory of a society for ‘distressed gentlewomen’ – is it the same thing?

LikeLike

Thank you for this post, and for a reminder of Mrs Smith – a brilliant character. I spent last summer rereading Austen and the Brontes (apologies for lack of accent) and being struck by the many references to knitting or needlework :) and now I have yet another reason to want to visit Edinburgh!

LikeLike

Although I am not very interested in the history of knitting, I found this post fascinating ! And I am now willing to read “Persuasion” (and to visit Edinburgh too, but it’s been a long time). I wish we had such thing like the Repository in France ! (Sorry for any mistakes, I read a lot in english but I don’t write very often…)

LikeLike

Thank you for such an interesting post. I do not wish to pry into your shopping habits, but I am curious to know how much these knitters charge for their work, particularly as you say that you feel that they could charge more. The examples you showed certainly look like they would take considerable time and skill. That aside, it is encouraging that you are able to buy handknits and know that the money goes to knitter. I, like other commenters, will have to re-read Persuasion…

LikeLike

If your craft tour of edinburgh includes craft supplies in addition to finished objects, please include the St Columba’s Kist charity shop on Leith Walk. If the Repository is where the gentlewomen of Edinburgh sell their handworks, St Columba’s Kist is where they destash. I’ve found lengths of Harris Tweed, 100% angora yarn and adorable buttons there, in addition to yarn and needles. They don’t have the resources of the larger charity shop chains, but they do such good work.

LikeLike

What a lovely entry. Should I ever make it to Edinburgh, I will be sure to stop by the Repository – what a marvelous horde of precious things! I think of Mrs. Smith now, and her knitting, whenever I happen to reread Persuasion. She’s not a character with as much definition as others in the book, but in some ways she’s enlarged by her similarities to the author. There’s a lot that’s said about her in the very silences.

LikeLike

What a fabulous post. I shall be sure to visit, and to have my visit enhanced by your contextualising words.

LikeLike

How fascinating that this sort of selling still occurs. I must try to visit this shop when I’m next in Edinburgh.

LikeLike

Fascinating! Characters like Lily and Mrs. Smith have stayed in my head, and are very relevant to me as a young woman college graduate trying to make a living and being passionate about crafting. I had never heard of the Repository, but I’m glad it was created and still exists– an interesting tack on “self-sufficiency” which is such a social work buzzword. Eagerly looking forward to more on this. (And I’ll be sure to avoid the shop if I’m ever in Edinburgh, as I’m sure I will want to take everything home with me.)

LikeLike

Fascinating! Thanks for a great post.

LikeLike

Thats fantastic – I had no idea (I must go and find them sometime soon). The idea of the tour sounds absolutely brilliant

LikeLike

Thank you for that post. I never knew this treasure trove existed. Next time I am in Edinburgh I will make sure I visit.

LikeLike

I’d never heard of this place…but of course will visit next time I’m in Edinburgh! Love the colours of your gloves….looking forward to more of the tour!

LikeLike

Thank you for this well written and insightful post.

I also hadn’t really thought through the situation of the “gentlewoman” needle worker in those times. I think I need to bring out my copy of persuasion and read it again…

Even today, though the stigma may be gone, not every neede worker knows how to sell their work. Hurrah to the repository for continuing to make a difference in these women’s, and perhaps their family’s, lives.

LikeLike

I’m intrigued, will hopefully pay it a visit tomorrow. I’ve only been knitting since Christmas and most of the blogs I’ve stumbled across so far have been from America.

I’m so glad I’ve finally found a brilliant blog in the UK (and in Edinburgh – meaning I can actually visit the places mentioned!) Thanks for all the interesting and inspirational posts:)

LikeLike

Similar, and not, is Miss Buncle, from Miss Buncle’s Book. And, oh, I’d like to visit the repository!

LikeLike

Really intersting to learn more about this place, I’ve never been in but always seem to be passing when it’s shut, will make an effort to go in soon!

LikeLike

I’ve been sitting here for the longest time looking at the blank comment screen trying to think of what to say. Sometimes your posts just blow me away! I’ve read “Persuasion” dozens of times and I’ve noted Mrs. Smith’s activities, but I’ve never really thought about what that meant. There are similar characters in some of Louisa May Alcott’s works (American, mid-19th century), and generally the genteel main character serves as an intermediary for the impoverished, needle-plying gentlewoman, recommending her to wealthy friends to do their dressmaking and mending. She also does note that the wealthy have an unfortunate habit of exploiting and underpaying those they employ.

A visit to the treasure trove is now on my “must do in this lifetime” list!

LikeLike

A wonderful and thought-provoking post that has me, yet again, regretting that I live half a world away. You and Ysolda both do a fine job of promoting your fair city and its many attributes.

LikeLike

That is really fascinating! I’m very interested in the history of knitting (and related crafts, but mostly knitting, as it’s what I do) as it relates historically to women’s social and economic issues. This has been a very educational post – and the knitted pieces are really beautiful! I am inspired in more ways than one. :-) I look forward to reading more of your thoughts and findings on this topic, and the craft tour sounds wonderful.

LikeLike

Ooh, I can’t wait to take “The Definitive Craft Tour of Edinburgh”!

LikeLike

What a great place and beautiful stuff. I will indeed go there when (if) I get to Edinburgh.

LikeLike

Thank you for this lovely post! I have recently found myself musing over the lucky position most of us knitters are in of knitting purely for pleasure and not out of necessity (whether economic or environmental). Certainly this has changed our relationship with knitting and yarn to one that is as much commercial as aesthetic– not necessarily, I would argue, a change for the worse. In this case, for example, combining the commercial and the aesthetic supports those who are genuinely dependent on their knitting. And what a nice impact it has on our relationship with yarn and knitting as well. Thank you again.

LikeLike