I have been knitting pockets. I am designing something which requires a pocket of a certain kind and I spent most of yesterday testing out several. By mid-afternoon, after creating a curious sampler composed of several different kinds of mini-pocket, I had a mild eureka moment, and devised what I reckon is the the perfect pocket for the garment I have in mind. It was a pleasant sort of day – I am generally fond of figuring out a knitterly conundrum – and I particularly like combining the activities of thinking with one’s hand and brain. While I was making my pockets, I was thinking about pockets, too.

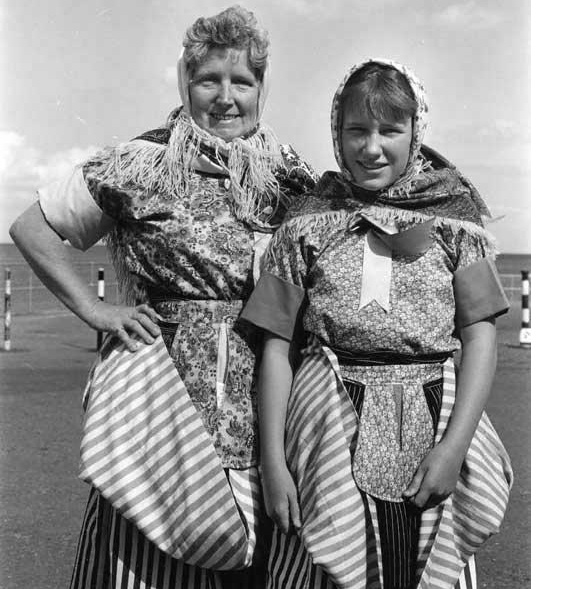

The pockets below, worn as part of the gala costume of these Musselburgh fishwives, have intrigued me since I saw them.

© East Lothian Library Services

They are very like the pockets worn by women of all classes in the Eighteenth Century. Such tie-on pockets could be highly decorative — miniature canvases upon which women of middle or upper rank might practice their needlework skills, such as this beautiful example from around 1720, by talented needlewoman, Hannah Haines.

© V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum

. . .or they could be plain workaday accessories, like this wonderful well-worn pocket, which turned up at the National Museum of Scotland with intact contents of a thread box, pincushion, pair of scissors and fleerish (firelighter).

© National Museums of Scotland

Pockets might be pieced . . .

© Royal School of Needlework

. . . appliquéd . . .

© Worthing Museum and Art Gallery

. . . made of woollen cloth . . .

© National Museum of Wales

. . . or even knitted.

© Leeds Museums and Art Galleries

(this interesting example is knitted from cotton in a durable basket stitch).

Worn, as they were, beneath the skirts — the repositories of letters, trinkets, secrets — pockets became a simple metaphor for a woman’s privacy and virtue. Haughty Meg, seen here in this illustration of Burns’ Song, is keeping hold of her pocket despite Duncan’s entreaties (you can see it beneath her white gown).

David Wilkie, The Refusal (1814) © Victoria and Albert Museum

And in Gillray’s cartoon, the picking of the Bank of England’s pocket makes Pitt’s plundering of Britain’s gold reserves deeply sinister and suggestive.

James Gillray, Political Ravishment, or, The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street in Danger (1797)

Like other working women, who needed quick access to cash or tools, eighteenth-century fishwives wore their pockets on the outside. . .

Mackerel seller from Paul Sandby’s Cries of London, 1760. © Guildhall Library.

. . . where they were vulnerable to theft. Old Bailey trials are full of fishwives whose pockets were pinched. But who would dare pick the pockets of Rowlandson’s formidable cod-carriers?

Thomas Rowlandson, Procession of the Cod Company from St Giles to Billingsgate (1810)

The differences in representation between the fishwives of Billingsgate and those of Newhaven interest me greatly. London fishwives are almost always stereotypically loud, rambunctious, filthy. But those of Newhaven and the Forth are represented as formidable in quite a different way — their physical strength is bound up with their virtue, and a beauty that seems exotic and Amazonian. . . or even Spartan. Perhaps Sir Walter Scott is to blame. He usually is. I think that this is my favourite of all the Hill and Adamson callotypes of the women of Newhaven.

Robert Adamson and Octavius Hill, Newhaven Fishwives (1843)

While, by the end of the Nineteenth Century, fashionable women had abandoned the tie-on pocket in favour of the handbag, working women continued to wear them. Some pockets evolved to more closely resemble money belts, such as this one worn by an Arbroath fishwife in a posed studio portrait.

According to Barbara Burman and Seth Denbo (to whom this discussion is indebted) “in living memory, working women who continued to make and use the old form were often in the fish trade”, which brings me full circle to the Musselburgh lasses at the top of this post. Rather than being anachronistic (as I confess I’d originally thought) their tie-on pockets are perhaps one of the last examples of a continuously-worn functional accessory that was once an integral part of the dress of every woman.

I have come a long way from my knitted pocket sampler. l shall save it for another time. But if you want to read more about pockets I highly recommend getting lost in the marvelous archive that is the result of Burman and Denbo’s research (the source of many of the images in this post). There are also some lovely examples of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American pockets in Linda Baumgarten’s What Clothes Reveal

So I also went down a pocket rabbit hole recently as well and am planning on sewing myself a tie on pocket from a pattern I found because I adore them! Plus, sock knitting while going for a walk(keep your yarn in the pocket and voila) if you were to write a pattern for such a pocket I would totally be knitting that, just sayin

LikeLike

I was extremely pleased to find this site. I want to to thank you for your time for this particularly fantastic read!!

I definitely appreciated every little bit of it and I have

you saved to fav to look at new things in your website.

LikeLike

Another wonderful morning reading your blog. How I look forward to them.

LikeLike

What a fantastic post! I love learning about pockets.

LikeLike

Fantastic! Thankyou so much for sharing this information and in such well written accounts and pictures! I’ve been reading a book set in the mid 1700s and the women refer to “pockets” but I could never envisage how that worked with their skirts until now! :)

LikeLike

Hi,

In Jane Eyre the girls at Lowood Institution are described as wearing “little pockets of holland, (shaped something like a Highlander’s purse) tied in front of their frocks and destined to serve the purpose of a work-bag”. It goes on to say the uniform suited them ill and gave even the prettiest an air of oddity,

Jane

LikeLike

Hope you’re okay, Kate. You haven’t blogged for a little while.

LikeLike

I saw a couple of local Roma women today wearing their standard ankle-length skirts and headscarves. From what I’ve seen they don’t really go in for handbags, but both were wearing bum bags round their waists. The detachable pocket strikes again.

LikeLike

I just wanted to tell you how much I enjoy these historical posts. Very interesting theme this time—pockets.

LikeLike

Hello I’m Amy from VADS and am glad to hear this collection has proved so interesting an useful to the wider textiles and knitting community.

We have lots more art and design images online to search at http://www.vads.ac.uk, and you can browse a list online at: http://www.vads.ac.uk/collections

The website is free to access and the images are generously contributed by a number of libraries, museums, and archives, which are mainly based in arts universities and colleges, as well as several public and private collections. They are free for use in non-commercial research or education. For any other purpose please contact the collection holders. Enjoy!

LikeLike

Have you ever seen the Lindsay Anderson film on Convent Garden?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Every_Day_Except_Christmas

I thought you might be interested – it focuses on the older generation of female flower sellers and also identifies the last female porter (if I remember rightly all flower porters used to be women at some point, i.e. when Victoria was on the throne).

LikeLike

My husband and I participate in Mountain Man Rendezvous (Pre 1840s Living History) and I actually have a workaday version of that very pocket style! I may have to give a go at a knitted version!

LikeLike

Fantastic post, thank you for the trip through the virtual world of pockets.

LikeLike

I love reading your posts like this. It makes me want to sink into historical archives and lose my way around bits and pieces like this. Who knew something so simple and generic in it’s day could be so fascinating? Thanks so much for your insightful and educative writings!

LikeLike

Fascinating post, thank you.

Having needed a ‘hands free’ existence at times in my life – crutches, disabled child, etc, I see the workability of these and am fascinated – I guess I would also prefer a shiny backing so that it would slide against the body-side. Our daughter is called Lucy, and I had put the ‘pocket’ idea as being a reticule, but these pockets are much flatter, and more interesting.

As an aside – having worked for a urologist, carpenter’s aprons have come to have a backing to the leather as the constant leaching of skin oils from bare leather gave the male genitalia problems – a little bit of useless information for you!

LikeLike

So this is what my Dad meant when he recited the nursery rhyme. “Lucy Locket lost her pocket, Kitty Fisher found it…” (I can’t remember the rest.)

LikeLike

Great post! Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Fascinating. Never would I have thought of a pocket as something so meaningful. Got a lot to learn! Thanks for the post. Loved the photographs of the fisherwives.

LikeLike

What a brilliant post, your blog is such a treat to read…

Love those Gillray and Rowlandson pics!

LikeLike

Do we get to see the trial pockets? And I want to make a patchwork pocket now ;-)

LikeLike

Re: the ribald connotations of the pocket and the ‘Lucy Locket’ nursery rhyme – the Kitty Fisher who found Lucy’s pocket is meant to have been Kitty Fisher the courtesan: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitty_Fisher

LikeLike

I feel incredibly silly, because I don’t think I’ve ever noticed or thought about pockets in the context of 19th century or earlier costume. How fascinating! And I absolutely love the 1843 image of the Newhaven fishwives – women I’d like to know!

LikeLike

Thank you for this utterly fascinating post. I wonder if the pockets worn on the outside might ever have been made in the same fabric as the skirt – that camouflage would make them less visible to pickpockets (a word which now seems invested with new meaning!), although I suppose it might also make them less interchangeable. Interesting stuff! And, as previous commenters have pointed out, they do look rather suggestive in shape: I can see how they must have been symbolically redolent, much more so than Germaine Greer’s ‘handbag-as-womb’ comparison – handbags are rarely shaped anything like a womb.

LikeLike

I posted some days ago, but I haven’t been able to stop thinking about pockets, and I see them everywhere! On waitresses, on builders (I mean, come on, tool belts!), on eastern european men (many of them wear little man bags with a great resemblance to pockets). And I am even toying with the idea of making my own knitting pocket so that I can easily move around without having to put my knitting down. Though I don’t really like sewing, so maybe I should talk my mother or my best friend into making me one for my birthday.

LikeLike

wonderful post, think the separate pocket should be revived. would make a wonderful book, by the response to your post there would be plenty of interest. I have a broken wrist, would be perfect for all sorts of things. can’y tie anything, velcro perhaps?. also a wonderful place to showcase ones handiwork.

LikeLike

Thank you for such a great post. My fiance’s mother is from Shetland, and has enjoyed your fishwife stories, photos and links. I have also loved the photos as my grandmother was a New Brunswick ‘sardine gal’. These pockets are fascinating. A little bit or ornament in such a functional hideaway sack!

LikeLike

How completely and utterly fascinating. The nearest I’ve ever got to one of these tie on pockets are the peg or knitting pinnies from the 30′ and 40’s. But those small ones are brilliant – I may have to look into reproducing and encouraging a trend away from too big handbags! Thank you for your always interesting and beautifully written blog posts. They are always such a treat to read.

LikeLike

what an interesting post. I come from Italy and now I’m wondering if Italian women wore the same ‘pockets’ around their waists… if only my grandma was alive for me to ask her…

She was an incredible seamstress/craftswoman… I’m sure she would have known…

Thank you.

LikeLike

I thoroughly enjoyed your post about pockets – also much thanks for providing sources to read. I’m a bit of a historical fashion fan myself, so this post was wonderful.

I’m with those who think traditional pockets would be a sensible alternative to the overloaded enormous purses and micro-pockets in most ladies’ clothes these days. My only concern is how to make them so they aren’t likely to catch on things as they’re going to dangle a bit when full (I’d want mine a fairly large size so that I could have a paperback/e-reader with me). It might make an interesting exercise in forcing ourselves to not carry so much stuff!

LikeLike

Until around this time last year I regularly wore a “pocket” to work. Admittedly, mine was originally a very small tweed shoulder bag (around 5″ square) and i’d shortened the strap so that it sat on my hips, but even so, my clothes had no pockets and I needed somewhere to keep my keys and mobile phone whilst walking around the building, so I wore the “pocket”. I always thought of it as a pocket in the way you describe them here, mostly because, as someone whose every day clothes contain no pockets whatsoever, i’ve always considreed them an eminently suitable alternative, and a good way to ensure that you don’t “leave your keys in the pocket of your other trousers”.

I’ve since graduated from my original tweed pocket (which sadly developed structural integrity-risking holes after three years ofconstant wear) to a leather one, which sits on my hip as the original cloth pocket did, and is resolutely NOT a bum-bag. In occasional moments I miss the inate”pocketness” of the original, even as I appreciate the practicality of my current model.

I suppose, in a way, i’m advocating pockets for today but given a modern twist. I know that several other women in the building in which I work have comented on both my versions and said how practical they were for wearing with skirts. Perhaps a revival is coming?

Melissa

LikeLike

Very interesting. I like the appliqued pocket, and the portrait of Elizabeth Johnstone (Hall), Newhaven Fishwife.

The images in the What Clothes Reveal, are so lovely, especially the embroidered buttons, and gorgeous waistcoats. I wonder what the wearers of these clothes would think of clothes today.

I think at first they’d be horrified by most of our everyday outfits.

It is curious how the artists represented the different area Fishwives; maybe it just says more about the artist..”beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Think that’s how it goes.

I must say I enjoyed your 4page article “Knitting Outdoors” with pictures, in Rowan Magazine number 47 too.

LikeLike

My mother made me a traditional folk costume from the north of Sweden and it has a pocket with strings not different from the fishwifes. The skirt is fastened with a single button with an apron over it, so it´s not that difficult to get access to the pocket as one might think.

Thanks for a very interesting post.

LikeLike

This is a fascinating post. I recently made a pair of pocket hoops, as part of the historical underwear for an 18th Century costume. Before that I hadn;t realised quite how practical elements of the outfit were :)

LikeLike

I think that the illustrations of fishwives being boisterous are probably more accurate. Most photographs back then were posed rather than candid. I can see those Newhaven fishwives getting their gab on as soon as the photographer came out from under his darkcloth.

Lovely post.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed that, Kate. Makes me think (always a good thing).

LikeLike

I love your costume history/feminism posts. This one is fascinating, and there is an obvious link between the pockets and sporrans, or a stonemason’s apron.

I was just thinking about pockets this morning, mostly how to put them in skirts that don’t have them. I like to have my hands free, and I don’t like to wreck my shoulders, so I am not a handbag woman. The original pocket looks very practical, and with a tie-on pocket it would be much harder to forget it and leave it behind!

LikeLike

Poor Scott! I love him dearly, but he has a lot to answer for!

LikeLike

Fascinating! And I’ve always wondered whether Bakhtin was blind to gender when he discussed “Billingsgate”…

LikeLike

So good to read an historical natured post, how it discusses the roles and view of women and, best of all, how knitting is involved. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing, Kate. This was a fascinating read!

LikeLike

Loved your post and would like to share it with our customers. I always find that the little things we don’t give much thought to- are often the things we never forget learning about. Thanks for sharing this!

LikeLike

I was going to bring up Lucy Locket who lost her pocket – I learnt about these sorts of pockets long ago thanks to that. Lovely!

LikeLike

Fabulous to see these wonderful pockets, Kate and hear about their history.

On a sidenote, have you ever read the book about Hannah Cullwick and her Arthur Munby? The photographs of the fishwives reminded me of it. Their relationship was very forbidden because he was a Victorian gentleman and she was a working class servant – they married in secret and had a distinctly SM relationship. Anyway, he was obsessed by working class women like the fisherwives and went around Britain taking photographs of them. He had a particular ‘thing’ for their strong arms and liked to take pictures of women doing hard, dirty work. All very taboo for the time, which no doubt was exactly why he liked it.

LikeLike

In an astonishing coincidence, I’m about half done with my own 18th-century knitted pockets! Sometimes I’m amazed at our common interests. Can’t wait to see your interpretation.

LikeLike

Kate, your stories are so amusing. Love the pictures and history lesson. I would love to see your pocket sampler too. ;)

LikeLike

Pockets are the main thing that annoys me about high street clothes; how come men’s clothes generally have better pockets than women’s clothes? I’ve never really got the hang of handbags and prefer to put wallet/phone/keys in pockets.

I have made something similar to the above pockets before for nights out when wearing a skirt. Nowhere near as beautiful as the ones above though!

LikeLike

So interesting. I had never heard of these pockets before. The closest thing I knew about were the Dirndl aprons of Austria, which could conceal all manner of things. Thank you.

LikeLike

When purchasing certain articles of clothing, pockets are often a sticking point. Can’t wait to see more about your pocket experiments!

LikeLike

sexaaaaaaaaaay!

LikeLike

Dear Kate

Marvellous stuff as always – and thanks to Gretchen too for her observation about the nursery rhyme with Lucy losing her pocket…I get it now too……great photos….and so so interesting….your post today coincided with a discussion that my Robbie and I were having this morning. We were talking about how difficult it is to understand the value of particular things at the time (we were bemoaning the loss of all those Dr Who episodes)…and how much it is luck and chance that some things survive and others don’t ..my handbag is really ridiculous when I think about it..particularly as it sits in a basket…a real metaphor for how much crap I carry around !!!

LikeLike

Wonderful post, thankyou :o)

LikeLike

What an interesting post! I often wondered how those pockets worked. I totally need one of those aprons. They look infinitely more useful than what I see as an apron and certainly better than my jeans pockets. I also like the pictures of fishwives which up until reading about them in blogs have just been characters in books for me (usually with the London stereotype).

LikeLike

I do love your posts like this – insightful, and usually on unexpected subjects! I confess that I don’t generally like pockets in modern garments – they’re placed without thought to their actual usefulness, so that they ruin the line and fit (if these have been considered at all, which they’re not in a lot of mass-produced clothes).

I look forwards to seeing your knitted pockets!

LikeLike

Marvelous post!

I wonder how long such pockets persisted on our side of the pond? I imagine pretty long, particularly in areas like the Cumberland Gap, Blue Ridge Mountains and the Ozarks.

LikeLike

How interesting! I’ve never given much thought to pockets, I have to admit.

LikeLike

This is really interesting and a fantastic selection of images – I’ll be browsing the VADS site with interest. I like the idea of pockets existing on the outside as they are shown in some of the images as a practical measure – this strikes me very closely as an archaeologist who needs a variety of tools and equipment on hand at all times. Myself and many others I know take to fashion something between giant pockets and a toolbelt to wear as easy access. Obviously the practicalities of some occupations still aren’t met by changing fashions!

LikeLike

Fascinating – really enjoyed this post. I immediately went and checked out some of Frank Meadow Sutcliffe’s less-posed pictures of Whitby fishwives, and they seemed to have formed their one-sided pockets out of their caught-up aprons, though it’s not always easy to see. But there’s a lovely photograph of Mrs Longster of Staithes knitting which shows her pinny pocket quite clearly. Can’t find it online, but it’s in Frank Meadow Sutcliffe – a second selection.

LikeLike

Hi Kate

if you follow this link it will take you to the pic

http://www.sutcliffe-gallery.co.uk/photo_3197834.html

We had found a copy of it hanging in a pub here in Bridlington yesterday and followed it through on the web.

Colin The Wool Boat

LikeLike

Wonderful article and the photos are so interesting! A pocket can also be a metaphor for keeping secrets ~ like keeping something under one’s hat or in one’s pocket. Not as risque as your allusions to virtue – LOL

LikeLike

What an interesting & informative post, thanks!

LikeLike

Utterly fascinating post…isn’t it funny how rarely we give the minutiae of everyday a second thought? Who knew something as simple as a pocket could hold as much rich history as it does personal possessions!

LikeLike

Thanks a lot for a great post! I knew absolutely nothing about this “pocket-trend”, but it sure is something worth looking into …

LikeLike

VADS is such a brilliant resource but so few of the images can be shared … great that the copyright restrictions on these allow them to be used for educational purposes. Thank you for a truly informative and fascinating post.

LikeLike

I was going to mention the awful bumbag, but Jennifer beat me to it (except she used the American name for it!). Now I want to knit one, patch one, applique one, embroider one …… but most of all, make one from Hinnigan fabric!!

LikeLike

Bumbag! You people always have better names for things!

LikeLike

Thank you!

Today I just search 6 words and I understand everything else.

That is a very interesting subject.

LikeLike

So these are precursors to the dreaded fanny-pack!

Much more pleasing to the eye, I love them all.

LikeLike

i always feel very lucky when you share these gems of research and information with us. how fortunate we all are that you have such curiosity and generosity. thanks for letting us peek inside these pockets of history.

LikeLike

Okay, let’s push pockets into a new fashion trend! I hate lugging a purse around and a cross-the-body bag is often cumbersome because it can’t lie flat against your body once you put in your glasses, wallet, lipstick, etc. But a beautifully designed pocket would be just the ticket. Please design one, Kate. Stranded knitting? Textured knitting? Please!

LikeLike

Kate, you are such a gifted writer, and I love te way you choose the perfect pictures to illustrate your text. Thank you, it’s interesting, informative and entertaining.

I’m looking forward to you showing us the results of your knitted pocket sampling at a later date :-)

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Kate – such a wealth of information here. I have been reading Moll Flanders and now understand that a particular scene with several references to private drawers and purses is probably even more suggestive than I realised – the pockets are certainly very ‘female’, as Jan points out.

LikeLike

great post! since you know about these things, tell me; where does the term steek come from? my dutch colleague told me that it means ‘stitch’….(we were having a conversation about why she should take up knitting)

LikeLike

Fascinating. The more I knit the more interested I get in textile history and I especially love your posts about East Coast fishwives.

LikeLike

I wish you had been my history teacher. I know you would have been able to keep me awake! Thank you for the lesson & the beautiful artwork to get me thinking today. I especially love “The Refusal”….exactly why does she refuse him? Does he have bad breath? Short temper? Is it the dog? I wish I knew.

LikeLike

Thanks for a really interesting post. It’s wonderful to learn more about our textile history in the UK.

LikeLike

Wonderful stuff, I definitely need one! They are rather, umm “female” aren’t they! There must be lots of rbaldry on this subject methinks.

LikeLike

In childhood I never understood how one could lose a pocket, as in the nursery rhyme that begins “Lucy Locket lost her pocket. . .”. I had no idea that pockets were once separate items, like waist-packs, rather than the built-in pockets of modern clothes. Thanks for another look at the history and meaning of women’s clothing.

LikeLike

Fascinating post! I really enjoy this information.

LikeLike

I am a relative new reader, I stumbled onto this site again while researching knit shops in Edinburgh, and got plenty of other Edinburgh tips to boot! Anyways, I just wanted to say, that these pockets are quite universal, they were used in Sweden as well, and are still considered a decorative accessory to many traditional womens costumes. And I think I need to research it’s relationship to the sporran, which must be at least inspired by the loose pockets.

LikeLike

I realize that if I had seen the pocket(s) in a museum, I would have thought, “Oh, that’s nice, a pocket.”

You have a wonderful ability to bring the past and the present together, while creating an awareness of the resourcefulness of women, their love of beauty, and their sense of self and duty.

LikeLike

What a fascinating post. I love all the pockets and can see the use for them. Probably a lot more convenient than a handbag which seem to be getting bigger and bigger. I have downsized greatly and still carry stuff I don’t need. I wonder what was carried around in those pockets?…foreby the thread etc. Loved the knitted one, of course.

LikeLike

Well now, that is such a coincidence! I have been wanting to make something similar in which to keep my mobile phone and lip-balm, when my clothes have no pockets. By golly I think you have the perfect answer for me, thank you so much.

I will be reading further as you have suggested, since I find the history of fashion extremely interesting.

LikeLike

I dearly love your posts like this.

LikeLike

Wow, those are gorgeous! I was just looking at my cowichen sweater’s pockets as it lay drying in my bathroom the other day, and wondered how they did that, knittingwise I mean, but these pockets here on your post are a whole new treat!

LikeLike