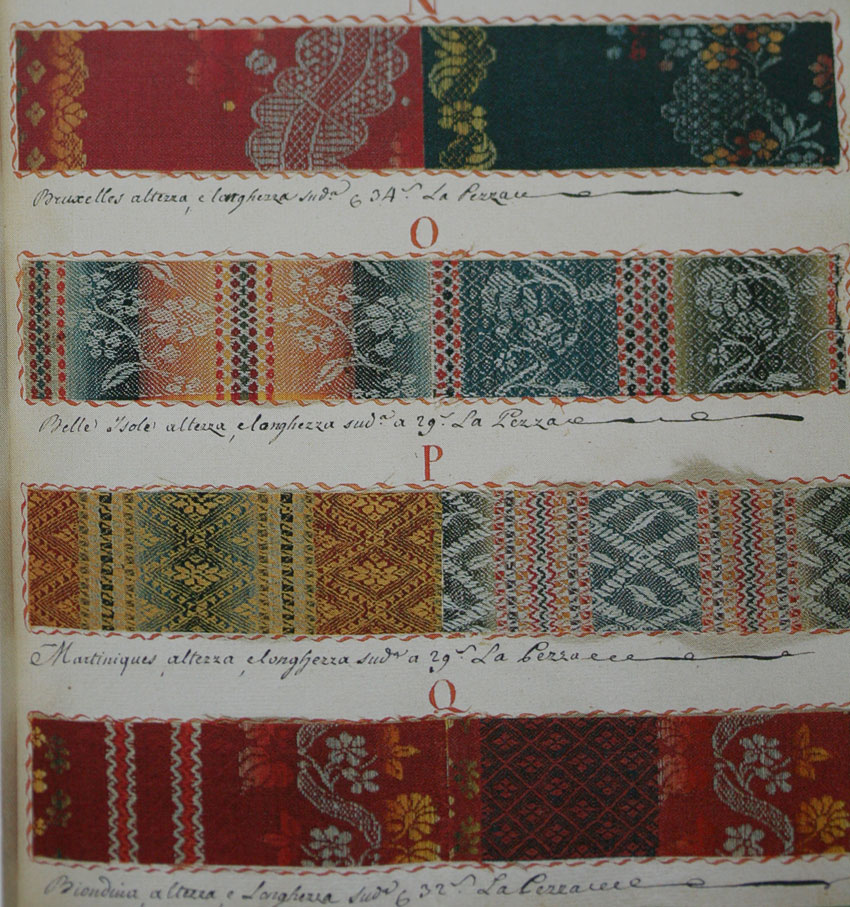

(Mid- eighteenth-century glazed Norwich worsted wools: Bruxelles, Belles Illes, Martiniques, Blondines.)

As we’ve seen throughout WOVEMBER, the way that textiles are named and sold can be misleading and difficult to understand. In a rush to make a chemical innovations integral to a brand, or to lay corporate claim to a particular spinning or weaving process, manufacturers are constantly in the business of re-naming and re-marketing the fabric they produce. While these fabric-product-names have an important function in selling textiles on to garment manufacturers, their significance seems to gradually get lost as the newly-named fabric travels down its chain of production. When it finally ends up as a finished garment, it is of course rebranded, renamed, and remarketed anew. The result of this is that the consumer has little sense of what the words on the label really mean. Did you know, for example, that lycra is the same thing as spandex or elastane or that tencel is simply a brand name of lyocel, which is itself a sub-category of rayon, which is made of wood? Really, it is no wonder that we are bewildered by what is wool and what is not.

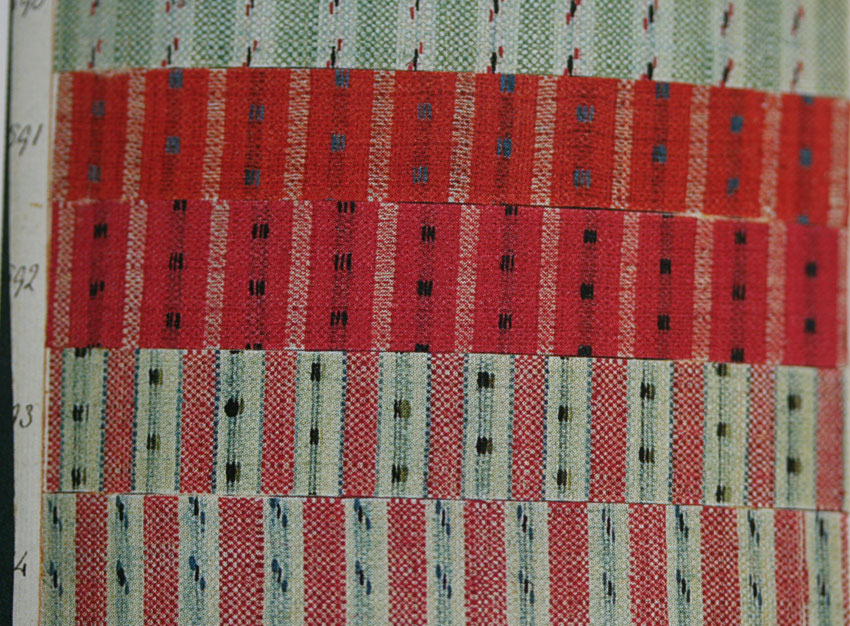

(Samples of eighteenth century tobines. These examples are glazed worsted wools, but tobines could be made of silk and cotton as well as wool)

But such confusion over the meaning of the names of commodities is really nothing new. Canny branding and re-branding, naming and re-naming is, of course, one of capitalism’s distinctive hallmarks. And, in a sense contemporary textile manufacturers are merely drawing on a marketing tradition that was already well-established in the early-modern British wool trade.

(eighteenth-century moreens, woven in Yorkshire. Moreens were furnishing-weight worsted wools, with a waved or stamped finish achieved by ‘watering’)

The swatches at the top of this post are taken from a mid-eighteenth century trade sample book. They are all dress-weight glazed worsteds, and were all woven in Norwich. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, following the successful development of long-wool sheep breeds in East Anglia; innovations in the processing of combing-wool; and a large community of Hugenot refugees (who were skilled designers and weavers); Norwich was the heart of Britain’s trade in worsted cloth (‘Worsted’ takes its name from a village North of Norwich). But as the seventeenth century progressed, Norwich found itself under competition from the burgeoning new woollen and worsted trades developing in the English North. In response, the East Anglian worsted manufacture successfully re-branded itself as the “new draperies”. But “new draperies,” needed new names, to distinguish themselves from the old, and such names also needed to appeal to the fashionable consumer’s sense of the modern, the novel, the exotic: hence Bruxelles, Belles Illes, Martiniques, Blondines in the top example. The newly-named glazed worsteds were extremely popular with the public, but some other English weavers, (in terms typically coloured by xenophobia) complained heartily about the Norwich Hugenots’ “outlandish inventions”. There was nothing new about the “new draperies” but their names, and these, the weavers complained, were mere ciphers to make the Hugenots’ textiles “more vendible”.

“In demonstration, thereof, a buffyn, a catalowne and the pearl of beauty are all one cloth; a peropus and a paragon all one; a say and pyramides all one; the same cloths bearing other names in times past. The paragon, peropus and philiselles may be affirmed to be double chambletts; the difference being only the one was doubled in the warp, the other in the weft. Buffyn, catalowne and pearl of beauty etc, may be affirmed single chambletts, differing only in their breadth. The say and pyramides may be affirmed to be that ancient cloth called a bed; the difference only consisting in the breadth and fineness.”*

For these weavers, the new draperies were little more than words, and simply illustrated the public’s propensity to be hoodwinked by fashion’s meaningless novelty.

Another impediment to understanding textile names (from a historian’s perspective, as well as a consumer’s) is that their significance is apt to change radically over time.

These rather beautiful scraps of cloth are eighteenth-century tabourets. These examples are fine Norwich worsted wools, frequently exported to colonial America, where, among fashionable circles, they achieved popularity in the manufacture of clothing. In mid-eighteenth century Philadelphia, you might well be wearing tabouret but, half a century later, during the early years of the early republic, tabourets of heavier weight were being imported from London to furnish the homes of Philadelphia’s new federalist elite. By the 1860s, and by now in exclusive use as a luxury upholstery fabric, taboratt was being manufactured in the USA, and was no longer woven from worsted wool, but from heavy cotton, or silk, or a blend of both. Apart from their names, what connects this series of quite different cloths all in popular use in North America over a century or more is their appearance: tabourets or taboratts all tend to be shaded and / or striped.

( eighteenth-century camlet. Another worsted wool cloth, camlets were also woven from silk, linen, or mohair. Camlets of different weights and finishes later became known as grograms, and groginettes, chinas and cheneys, harateens and moreens)

I have two points to make here. The first is an obvious Marxist one about the way in which finished commodities always disguise the stages of their own production. Whether it is a wool-flannel shirt sold by Urban Outfitters that is actually entirely made of cotton, or a bolt of glazed worsted pyramides that was once simply known by the homely and far less exotic name of a bed, textiles are in the business of constantly being renamed, redescribed, and rebranded in order to sell themselves. The second is that the meanings of commodities – as well as the commodities themselves — are subject to change, not just through canny marketing, but, like tamouret or tamoratt, through their contexts and the way in which they are used. To my mind there is no reason why we can’t wrest the word wool back from meaning all yarn, or all warm and fuzzy cloth (as it clearly does for some UK retailers) to its correct application to cloth spun, knitted and woven from the fleece-of-the-sheep.

And we purportedly wool-aware folk in the UK are very much at fault here as well. Among UK knitters, there is a curious and totally intractable attachment to the phrase “wool shop” (for yarn shop) and “wool” as a generic term for whatever yarn they happen to be knitting with at the time. The words yarn and yarn store are the focus of weird resistance by some British knitters, who regard these terms as a terrible Americanisation of language amounting, in their eyes, to a sort of imperialistic imposition. (Bizarre, I know, but all too true) But, dear countrymen and women, it is nothing of the sort: with the word ‘yarn’, North Americans are simply using the English language correctly, while you, who stubbornly continue to refer to all yarn as wool “because it is British” are completely incorrect. In short, British knitters, why not start saying YARN?

* See Robin D Gwynn, Hugenot Heritage: The History and Contribtion of the Hugenots in Britain (1985; reissued 2001).

I’m regularly asked if I produce wool (largely by Americans but also by Brits); no, only a sheep can do that. I produce woollen cloth, made from woollen yarn.

I’m afraid this is just symptomatic of people’s misunderstanding of manufacturing processes.

LikeLike

I’m coming late to the discussion, but my pet peeve is misuse of fabric names — right now, in the US, every slubby silk is called dupionni, when probably it’s a somewhat unrefined shantung. Duppioni specifically references a double fiber that a silk worn extrudes. It’s not common. Also, remember back in the 70s and 80s all the challis running around, wool or otherwise? Well, that ain’t what it was.

LikeLike

As a colonial I had always used the term “wool shop” despite often being disappointed by the lack of wool therein. I take your point and will assume the term “yarn shop”, or in the more unfortunate cases “acrylic shop”.

LikeLike

Very interesting! It’s nice to know why my mother insists on calling everything wool. I did initially, but after a bit of internet exposure and learning about fibre content i find it more natural to say yarn. I also get more joy out of saying ‘yarn!’ like a pirate.

LikeLike

I agree wholeheartedly with Ros. Would you argue with cottonwool? Wool (and its equivalent) is used to mean yarn in many languages.And incidentally check your OED, wool isn’t just from sheep. Interesting that it doesn’t seem to have occurred to you that whereas in the UK “worsted” means a particular type of woollen yarn or the fabric made from it, in the US it denotes a particular thickness of yarn and you don’t hear/see English knitters get all righteous about that. The word “blanket” originally pertained to a particular type of woollen fabric but can now be made of any type of fibre because the word has transferred to the purpose rather than the origins and wool as knitting yarn has made much the same transition whilst retaining other senses (eg hair of sheep, goat, or similar animal) no doubt because when knitting first became a popular hobby, before the creation of synthetic fibres, knitting yarn almost certainly was wool. And wool shop persists in the same way that older people might refer to record shops even though the local music shop in all probability hasn’t sold a record for twenty years.

LikeLike

Appreciate your point of view. You’ll see a careful excavation of the meaning of ‘wool’ in the – not always infallible – OED in my previous post, in which the word’s application to cotton and other fibres in compound form is also discussed.

LikeLike

Oh no!! I am one of those “older” people that speak of “records”, listening to “records” and going to the “record store”. I have no problem with calling a yarn store a yarn store though. I am in Canada and I have always been able to tell the difference between wool and the other stuff. Although the British use of “wool shop” sounds very nice to me. Kind of hopeful and promising, until I am greeted by shelf after shelf of novelty yarn. I am still rather woolly on the term “worsted” though…

LikeLike

I promised myself I wouldn’t comment again but it seems I can’t help it. I just can’t understand the notion of ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ meanings of a word. Words mean what they are used and understood to mean. If I say ‘wool’ meaning ‘stuff I knit with whatever it happens to be made of’ and other people understand that’s what I mean then that is a perfectly ‘correct’ usage of a word. I just don’t think you can be directive about language in the way that you would like to be. That’s not how it works.

LikeLike

Your writing and research is always so very interesting. I love all these sample cloths.

Imagine living back then and dressmaking with these beautiful fabrics, and also for the furniture.

Must have been hard for the poor to have beautiful garments, but perhaps if you had weaving skills you may have been able to have at least one best outfit.

I remember a bought brand which was of high quality here in Australia, Pringle of Scotland, beautiful and soft and beautifully finished, they were Pure wool.

Got to reclaim the word “wool,” for only true genuine woollen knits and fabrics, you know where you stand when it comes to dealing with 100% wool fabric, ie: if labelled properly with what type of wool etc you know how to launder it, and what to expect from its wearability, and how much it may stretch/grow, or shrink.

The artisans/weavers who made these cloths shown you have shown us Kate, are/ have been in their time amazing.

LikeLike

also in german the usual word for yarn is : wolle. wich means wool. so like if you say: sockenwolle = sockyarn.

i myself dye sockyarn and sell them, and i wanted to print on the etiketts sockenGARN ( garn=yarn) , some friends told me to change to sockenwolle (sockwool). as a Hungarian i didnt argue with that idea, but it is also not really familier to call yarn wool, because it is not always out of wool. right?

LikeLike

I spent two years living in the US where I Iearnt to knit and rediscovered my love of all things fibre related. I most definitely picked up my determination to distinguish between ‘wool’ and ‘yarn’ in the States. Now back in the UK, I continue to say ‘yarn shop’ rather than ‘wool shop’ despite looks of disdain, bemusement and downright hostility from family, friends and co-workers, so it will be no surprise to you that I whole heartedly agree with the sentiments of your post!

LikeLike

Hi Kate–Enjoying your commentary as ever…as a bit of a sideline (and also in relation to David Westcott’s comment above) Roslyn was telling us a great story today about all the wartime initiatives to create fibres out of new (or old) materials: I can’t remember which exact one, but there was a fibre developed by a California company in I believe the 1930s/40s that was referred to as ‘Shetland spun’–she’s trying to track down some more info about this, but raises a really interesting point about the association of particular places associated with sheep/knitting lending an aura of ‘authenticity’ (whatever that means!) to laboratory innovations…Let’s try to get together soon!

All best, Marina

LikeLike

I’ve been saying yarn since I worked for Patricia Roberts in the 1980s. She stocked so many other things apart from wool – silk, cotton, etc., that it was essential. It stuck.

Love your last couple of posts and the accompanying pictures. I feel somewhat guilty not to be paying for all this information somehow.

LikeLike

These descriptions of different hats from REI Outlet online are true to fiber content, but appeal to people’s sensibilities toward words associated with wool, ie: cozy and warm (and some negative connotations too)… Marketing is wonderful, isn’t it? :-(

(I still remember when received my first wool sweater without the lanolin washed out, it was and is very warm and darn near waterproof in a deluge. Still love that sweater! Warmest sweater I’ve ever owned.)

Just a few description examples of popular brands today, available not in wool, or some only in partial wool! :

•Soft acrylic insulates even when wet, but unlike wool, it doesn’t itch, and it dries quickly when damp

•Cozy acrylic keeps you warm without being itchy or uncomfortable

•Made from 100% high-bulk, low-pill acrylic yarn; it’s easily cared for and stays warm even when wet

•Soft acrylic provides the warmth of wool without the itch, and it dries quickly

•Natural and synthetic blend fabric offers exceptional warmth and is moisture wicking for all-day comfort

A look at the fiber content: 43% polyester/19% recycled wool/19% wool/17% nylon/2% other fibers

•Multipanel knit construction; fabric blend combines the natural warmth and durability of wool with the easy care and softness of acrylic

Another look at fiber content: (Top) 50% wool/50% acrylic / (band) 85% acrylic 15% wool

•Wool and acrylic blend supplies the best attributes of both: the natural warmth and durability of wool and the easy care and softness of acrylic

SO:

Wool = itchy, wet, (doesn’t dry quickly…?) ?

Acrylic / etc. = soft, dries quickly, comfortable, warm, moisture wicking, easy care…. everything one would want in a good wool hat!

LikeLike

I have always said “yarn,” and it always made me cringe when people called it “wool” when referring to something to knit with. My grade 5 teacher used to drive me crazy as a 10-year-old whenever she called it wool… what we were using had never been anywhere near a sheep!

LikeLike

Interesting as always! I’m really enjoying wovember and thinking about wool. I am definitely one of those (UK) knitters who grew up with wool shops and wool = any yarn at my grandmothers knees. One of my grandmothers was a terrific knitter – in the 1940s and 50s she would be paid to knit outfits for people – twin sets, skirts (!!!) and jackets – that sort of thing. And she could whip up an arran sweater in no time without ever referring to a pattern. But despite her enormous prowess and skill – she also used a lot of nasty acrylic yarn particularly in the 1970s and 80 when I was growing up. I remember a truly horrid jumper which she made for me one year with her knitting machine. it was peach coloured with a row of skiiers around the bottom. The skiiers were in black yarn and if that wasn’t bad enough, the floats on the back of the fabric showed through and it looked awful. I never wore it.

But just because my grandma said wool shop and only ever knitted with ‘wool’ (even if it was plastic wool) doesnt mean I have to. I have been talking about yarn and yarn shops for quite a while now. I dont think it’s ever resulted in a funny look! But, having said that most people think I’m a bit bonkers about knitting, so they have come to expect some accompanying eccentricities…

LikeLike

What incredible skill those 18th century weavers possessed! How amazing it would be to wear garments (or indeed decorate one’s house) with such fabrics.

Like others, I too have spent my life knitting with balls of wool (not skeins of yarn) bought from wool shops, not yarn stores. But I am changing my ways, mainly through daily exposure to Ravelry.

From now on I shall cast off any stray lingering thoughts of American linguistic imperialism. Instead I shall embrace terminological exactitude with a strong sense that I am doing the Right Thing :0)

LikeLike

Around here, belgium and The Netherlands we call yarn “Breiwol” (knittingwool). I suppose it is the same as everywhere else; because all the yarn used to be wool the words are still the same.

LikeLike

I grew up in a family of knitters in Australia who call everything knittable ‘wool’. It’s only in the last couple of years that I’ve discovered the world of ‘yarn’, and started to realise how daft it is to call all knitting string ‘wool’. I’m trying to re-train myself with reasonable success, except for when my brain goes into tired mode (often, gah!).

I’m really enjoying reading your posts at the moment – I love LEARNING about yarny stuff, and you’re providing the opportunity in bucketloads. Thank you!

LikeLike

It is not just your countryfolk who wear this mantle of shame! I was raised with the term ‘wool’ being used where yarn should have been – but then it was very rare for me or my family members to knit with anything other than wool (and if it wasn’t wool, it was at least a closely aligned animal fibre). And there I suppose lies the root of the terminology use. As an adult now much better versed in correct useage I invariably encouter people who use wool instead of yarn as I did and am conscious of it. On the upside it is a testament to the power of the wool ‘brand’ that all yarn follows in its wake.

As always, I am loving your posts Kate.

LikeLike

As an American, I, too, used to call what I knit with “wool,” because wool was all that was available and all I ever knit with (well, acrylic was available, but not to my liking). It has only been fairly recently that I made the switch to “yarn” simply because alpaca, silk, fine cotton, and linen are, obviously, not wool.

I’m very much enjoying your posts and Wovember!

LikeLike

I’ve been listening to Jake Thackray recently and so, to mark this, your brilliant, fifth (pip?) post of Wovember, I send you the Swaledale sheepie countings of old Molly Metcalfe (and Mr. Thackray, at his self-deprecating & wry, purple-shirted best): yan, tan, tether, mether, pip! (http://youtu.be/TiXINuf5nbI) I look forward to reading Wovember posts all the way through to jigget…

I wonder, would it be impolite to express my longing for a techno-breakthrough that would provide a tactile, onscreen equivalent of scratch-n-sniff? Such a thing would allow me to get overly familiar with those gorgeous fabric swatch ledgers, which (I must admit) I covet.

Finally, a question about glazing: is this an effect imparted to the wool fabric resulting from heat-pressing, and/or does it include an actual additional glaze (and if so, what would have been used for the glaze material)?

Thank you ~

Jane

LikeLike

Although I wouldn’t say that I have a sentimental attachment to using “wool shop” (like Maureen does), it’s still a hard habit to break! Saying “yarn shop” still feels like an affectation, even though I’ve been trying to train myself out of “wool shop” since I started knitting and learnt of the evil squeaky acrylic (which is actually what my local yarn shop seems to have most of…) It is because it strikes me as an Americanism that it feels affected – it almost feels like adopting some new cool slang to fit in with the popular kids. I really don’t know any other knitters apart from my mum (who of course, is a “wool shop” sayer), so when I say “yarn shop” to her, it draws a another distinction between her (straight needles, paper patterns, pretty old-school) and me (circulars, pdfs, loving anything new…) Not quite what is wanted…

I think that if we need to do some consciousness-raising on this ‘wool/bloomin’ well not wool’ issue, there might need to be a more positive take than I got from the last two paras. My first reaction was “But dammit, I feel guilty when I don’t buy British wool! I’m scrutinising labels to find out what’s in yarn! And it’s me that’s part of the problem?!” I certainly don’t think they’re meant to be accusatory – but now I’m off to do a bit of counter-revolutionary knitting with my merino-cashmere-possum YARN (from New Zealand).

(I really enjoyed the rest of these two articles, as I usually do. I totally agree that the lack of labelling regulations seems like a crazy oversight. If they can legally distinguish between strawberry-flavour and strawberry-flavoured yoghurts, why can’t they sort yarns and fabrics?)

LikeLike

I am English but have lived in America for a great many years. It has taken me a really long time to say “yarn” as the locals do!

I still slip sometimes. I too remember “the wool shop” where you could go and watch your Mum buy yarn (!) by the ball, while the owner kept enough for the whole project in the shop for her. Buy as you go method. Those were the days!

Anyway, wool is still my favorite yarn!

LikeLike

Never knew such a problem existed. Here in the U.S., or maybe on the East Coast, wool is wool, and acrylic is acrylic. Course, I always read tags. I think it may be deliberate mis-marketing. Wool usually commands a higher price than a acrylic/poly dress, for example.

LikeLike

Really interesting blog, thank you for sharing your knowledge. There was a mention on Radio 4 this morning about textiles and the Hugenots, facinating history. looking forward to the next installment.

anne

LikeLike

in the odham’s big book of needlework, which i got on your reccie, thank you very much, and which i was consulting the other day on the matter of invisible mending, the end of the thread one is using to darn a hole in fabric of any provenance (ie.. cotton, wool, wood, orlon) is referred to as the end of the wool. in other words, the working fiber is wool.

so much for the language we share which divides us. a good yarn!

LikeLike

These language troubles are not restricted to English. Germans usually call all knitting yarn “Wolle”, although the word “Garn” exists, too, but is more often associated with sewing or embroidery thread. Retailers and producers might use “Handstrickgarn” – hand knitting yarn – in adverts and the like, but it sounds rather posh.

But well, we also call cotton “Baumwolle” – tree wool – because we’re crazy like that.

LikeLike

‘Baumwoolle’ is fascinating though – it dates back to the early introduction of the fibre into Europe, and no-one knew where it came from. It was woolly, but not from sheep but plants so – tree-wool! Perfectly logical. I’ve seen some lovely little Medieval side-margin illustrations from manuscripts of trees bearing little lambs in pods – which look remarkably like cotton plants except for the sheep!

LikeLike

Oh yes!

I am with you Mona and Kate!

I’m from germany and if you go into a “Wollgeschäft” (wool shop) and ask for wool, they offer you acrylics or different blends.

I always have to ask for 100% sheep wool yarn. It’s the same thing with fabrics and neary impossible to get pure wool ones.

LikeLike

As far as I know ‘wool shops’ are so called only in the British Isles. I can appreciate the sentimental attachment some knitters have to the usage, but fail to understand why they resist the term ‘yarn’ which is used not just in America, but in other countries as well.

Once the shops were ‘wool shops’, but some of them deteriorated into acrylic shops.

LikeLike

I almost always learn something new after reading one of your posts, thank you for that!

When I read your previous post on the subject of wool, I was really surprised at how untruthful your clothes labelling is. Something like that would never be tolerated here (Sweden) and I think it might even be against the law. I had never seen it until your examples.

Regarding the use of yarn versus wool, I can understand the historical aspect of wool being the predominant fibre and therefore becoming the equivalent of the word yarn. The whole business about yarn being an American word is funny though, considering how old the word is and that we use the “same” word in Scandinavia and Germany (garn, Garn).

http://www.britannica.com/bps/dictionary?query=yarn

Main Entry:1yarn

Pronunciation:\ˈyärn\

Function:noun

Etymology:Middle English, from Old English gearn; akin to Old High German garn yarn

Date:before 12th century

LikeLike

I always learn something! This is a very interesting topic, and the fabrics shown here, as always, are just gorgeous. I’ve been interested in textiles, and learn so much from Kate’s writing and research, much more than when I do so on my own. Kate has a wonderful way of pulling together information that is fascinating and most always beautiful. I do love the photographs in so many of her posts.

LikeLike

Many Australian knitters still refer to all yarn types as wool mostly because that’s what you were knitting with – all thoose bloody merinos around the place! I have come to use yarn as a generic term and my mum is becoming accustomed to the difference.

I think what really broke my use of the word wool was when all those nylon, eyelash yarns were so popular. Nobody could look that in the eye and call it wool!

LikeLike

Though I have never used the term “wool” to mean “anything and everything to knit with”, and though I have heard friends from Ireland specify “wool shop” as being where they purchase their knitting materials, regardless of whether it was wool or not — albeit knowing the difference between wool and another fiber; something I also find interesting is the Anglophile attitude among many Americans who use British spelling and terminology as if to set themselves apart, such as “fibre”, “theatre”, “centre”, and so on, as well as specific words not commonly used in the US, but commonly used in Britain. Also, I have seen many uses of “Haus” as in “Coffee Haus” appropriated from German language, “Sweet Shoppe” (spelling and wording from Britain) for Candy Store, or Candy Shop, and I am sure anyone can imagine, or has witnessed all the uses of foreign language and colloquialisms from other countries in the naming of buildings, streets, businesses, coffee, beverages, food, clothing, even children’s names, etc., as a popular trend for quite some time. Marketing has everything to do with this, it seems we, in America (though certainly not all…no grand generalizations here) are blinded by the new and the novel, even if it is traditional in another country. Anything to get the attention of a shopper, a customer, is fair game for marketing and marketing departments. There is a definite Anglophile attitude amoung some Americans, and the propensity to basically copy the mannerisms of another country’s people in order to further their perceived social status is a sad commentary on some American usage of language, and need for what is an obvious attempt at noticeable upward mobility. Aligning oneself with the English, and looking down on “terrible Americanization” (we spell it with a “z” ), [these same] Americans attempt to imitate the English to whom they look up to. Again, this is not a sweeping generalization. There has always been a divide, comfortable or not, between the spoken language of the British and American people, and often, whether conscious or not, the emulation of British mannerisms is perceived (by some) as a higher class of speaking. Or… for what it is… an attempt to associate oneself with whom one admires. Of course most Americans have heard the term “ugly American”, for which many would opt to separate themselves through the genius of marketing, which appeals to the Anglophillic aspect of the American psyche. Or, simply not eat lots of Quarter Pounders with Extra Cheese :)

Regardless of this fascination of mine, of Anglophillic Americans, I remain consistent with the term “wool” meaning fiber from sheep. Having read a previous posting by another spinner, I realized that I most likely use the term “fiber” because I am also a spinner, and thus place emphasis on the many differing fibers available.

My point on “terrible Americanization” is not meant as a derisive comment toward anyone, nor is it to bring to attention to the wording, except to make the point which I have observed as true.

Language is definitely manipulated by the marketing directives of corporations hoping to capitalize on the preferences of people.

LikeLike

I was shocked when I went to the US and saw how many shops are called ‘shoppes’. Here in the UK, it’s an archaic spelling that you would only ever see on ‘Ye Olde Tea Shoppe’ or similar. So it’s a very weird way of appropriating it when you see the state-owned liquor stores in PA called ‘Wine Shoppes’.

LikeLike

That would be! Haven’t seen that particular usage, but find it funny. Now that I live in a state that has only state owned liquor stores, (as opposed to another where it isn’t regulated in such a way), I am constantly surprised that liquor is only available there. I would love to see Wine Shoppe just for the fun of it, and have seen worse, as a restaurant in a southern state named “Roadkill Restaurant” !! There is something “quaint” (?) about the spelling of “shoppe”, and that might have something to do with the use of it in the states, alluding to a imagined time when things were more, well, quaint? I’ll freely admit, an English friend of mine has the best accent that just makes me swoon when I hear his voice. And for you, he would have no accent at all! Or is that generalizing too much? Also, I am curious of the name, Wine Shoppe, as beer and wine can be bought in grocery and other stores, but not liquor, in states that have laws allowing liquor to be purchased only in state owned stores, so I wonder why the term “Wine” in “Wine Shoppe” was used as the name of a state owned liquor store. I really don’t know. Have to ask, I guess.

LikeLike

I have to admit that I’m surprised that there isn’t a truth in advertising rule about fiber content. I think there *might* be one here in the U.S.; I remember reading at one point about a fiber-content lawsuit about a yarn that purportedly contained 5% cashmere, but on analysis, sometimes contained none. Ah, here’s a blog post that provides a good summary:

http://www.girlfromauntie.com/journal/trust-no-one/

And here is the full listing of legal documents:

http://www.cascadeyarns.com/lawsuit.asp

Interesting, no?

But oh, those lovely fabric samples! How I would love to get my mitts on a length of any of those! (Am I right in thinking that those would also all be natural dyes as well? Based on your dates, they predate aniline dyes, yes?)

LikeLike

I grew up with Grannies who spoke of wool as that was the only thing they could get to knit with. The “wool shop” is a phrase stuck in my brain from them plus they also taught me how to knit. Breaking the habit of saying wool, as a catch-all, feels like I’m breaking my connection to them and since neither of them are with me anymore that feels hard to do. there’s a linguistic sentimentality attached to my use of “wool” and “the wool shop”.

LikeLike

I do understand this, Maureen – my downstairs neighbour (and fellow knitter) feels exactly the same way. Those phrases are in themselves important connections to our families, our knitting heritage. . . it’s tricky.

LikeLike

Your gran used wool to describe all the things she knit with because the only thing she knit with was wool. If you use the term “wool” to mean “yarn” then you’re devaluing her work. If you want a sentimental attachment to your gran and her use of wool then use wool – yarn-from-sheep – like she did. Otherwise your “sentimental attachment” is just a malapropism.

LikeLike

I can’t speak for Maureen’s gran, but my gran not only knitted with but also sold acrylic and other non-wool yarns. All of which were called wool.

LikeLike

A fascinating article, thank you Kate. I have no problems with yarn rather than wool! It is nteresting how names and their meanings change over time. I think of the shoddy textile trade in Yorkshire and how the word seeped into general useage.

LikeLike

I was surprised to read a commenter above saying that in Canada people s/he has heard people refer to yarn as “wool”. I’ve never heard that here in the West…maybe it’s region-specific (which would seem to be the case as the Newfoundlander in her example uses ‘homespun’, which is going a step further). I live on Vancouver Island and people here seem to be very fibre-aware. I was teaching someone to knit (with my own yarn) and I said “so now pick up your wool” and she said “Oh, is this wool? I thought it was acrylic.” And this is from a non-knitter. I was very pleased.

So, reading your series on re-sheeping the wool, I’ve been continually surprised at the need for it, since where I live awareness of wool and correct textile terminology/labelling is very high. Judging by the comments and your examples, though, I’m one of the lucky ones!

LikeLike

I love the phrase “resheeping the wool”. I hope it becomes widely used! I asked for “yarn” at a shop in western Ireland and got the funny looks too – and thought quickly and rephrased it to “wool”. I was actually looking for wool yarn, and that’s what I got!

LikeLike

Here in Nova Scotia, when I was growing up, everything yarny was indeed called “wool”. I believe that only with our newest knitting resurgence has the terminology changed at all. I have been intimately involved with fibre, whether weaving at art college, crocheting, crewel, “ma-crummy” or knitting & can tell you that only quite recently (maybe within last 10yrs. to 15yrs.) has the terminology correctly morphed to a distinction between wool & yarn.

As always, a fascinating article & a cause I can fully support: thanks Kate!

LikeLike

Growing up in Ontario in the 1970s, I do believe that collectively we used the word “wool” to refer to all yarn, because I recall doing the same myself into my early adulthood (without awareness that I was applying the term to mixed yarns). As a culture, we’ve probably transitioned gradually to “yarn” as our knitting has changed to incorporate more and more blends and cottons and so on. As a girl I was still carding my grandmother’s fleece so that she could spin it, so likely both my mother and grandmother were using “wool” merely because they were, indeed, knitting only with sheep’s wool.

LikeLike

Every one of the swatches in the sample books you show is a beauty. If only such fabrics were readily available today! One of my great-grandmothers is said to have come from a Huguenot family (according to relatives who offer no proof whatsoever), so now I can fondly imagine that distant ancestors may have produced these.

Two decades ago, silk clothing (thermal underwear, etc) for active outsdoorsmen and -women was marketed in the US with the slogan, “Only silk is silk”, with a description of all its uniquely valuable characteristics that could not be duplicated by synthetics. What we need now is to teach people that only wool (baa-baa, sheep!) is wool. So sad that Britons seem to have lost that understanding. I second Jen above – more power to your arm!

LikeLike

Oo yes. I am quite the cheery evangelist when it comes to wool’s awesome properties. It’s a source of quiet bemusement in the family (some of whom have sheep flocks (mixed meat and fleece)) that I am so excited the stuff. I always find it mildly exasperating that to them “sheep flock” = merino, or perhaps corriedale if you’re being unusual.

LikeLike

I think referring to finished products not made of wool-of-the-sheep as “woollen” is dishonest and bad form, but saying that we must reclaim the word “wool” to mean only the sheep’s fleece and never yarn is linguistically short-sighted–and a losing battle. It doesn’t need to be done because when we talk, we can disambiguate the word as we always have–no knitter really expects to only find woollen yarns at a wool shop, and I’ve never interacted with an English or Irish or Australian knitter who didn’t know that sometimes “wool” refers to any yarn and sometimes to the fiber of the yarn. If we’re going to say that “wool” can have one and only one meaning, why not also say that a “trunk” may only be the bole of a tree and not a storage box or the part of a car some folks call a “boot”? When I interact with a non-knitter who is confused about a reference to “wool” that seems to mean more than sheep fleece or scratchy sweaters, I am sure to explain to him what the deal is there.

On the other hand, it’s quite possible that the march of time will take us in the right direction with the narrower meaning of wool anyway. We Americans, great consumers of yarn that we are, will probably keep asking people to refer to “yarn shops” instead of “wool shops” so we can find them (in say, a pre-travel Internet search), which will lead to shop owners labeling their stores as such, and so on and so forth. I would also not be surprised to learn that the all-yarn meaning of “wool” is already on the way out, but I’d need to do some research to confirm that.

LikeLike

What bothers me the most is how gullible we are as consumers. The language they use is smoke and mirrors to get us to buy, buy, buy. Are we so dull that we cannot think for ourselves? ( I guess the answer is yes- because I like to shop as much as the next person).

LikeLike

I am old enough to remember the time when wool shops did actually sell ‘knitting wool’, because there wasn’t anything else, and I hate the way ‘wool’ now apparently [in the UK] means any knittable yarn.

Power to your elbow – please keep going.

LikeLike

Thanks for the great article. As a spinner and weaver I find the vocabulary frustrating and sometimes infuriating. It gets even worse when you consider that some names are used both for size, as in “worsted” weight yarn and also for type as in “worsted” yarn which is spun from combed fiber using a short draw under compression. Even the sheep names are misused. Harrisville Designs (www.Harrisville.com) uses the terms “Shetland” and “Highland” to label their two different weights of yarn, with “Shetland” being 900 yds. per 1/2 lb. cone and “Highland” being 450 yards per 1/2 lb. cone. Both are made of the same fiber which, although made from fleece, doesn’t seem to be predominantly from either Shetland sheep or Scottish Highland sheep!

LikeLike

Excellent post. I’ve personally been fighting this one for years, just because it’s so wrong to call all yarns wool. Let’s carry on with the wresting…..( and don’t get me started on the inaccuracies in textile structure descriptions ).

LikeLike

When we first moved herem a couple of years ago, I went to the posh farm shop across the road (very posh, locally sourced, hand-knit- organic-muesli type of place) and ask by the way, do you know where the local wool shops might be found. Quick think, and yes, Mrs .. in the village does wool, and would be able to order too probably. Hm. That would be the hardware store, who have a trolley that they put outside with the buckets and brooms, which contains really cruddy acrylic in all those colours that hurt your brain. I’m guessing that farm shop lady is not a knitter . . . .

LikeLike

I’m a wool sayer too. Can’t help it. My gran knitted knee high socks for us all through childhood (no chilblains for us) and I would be sent up to the local drapers to get the necessary supplies of “worsted fingering wool” (ie fingering weight, worsted spun yarn). I don’t remember that the shop stocked anything other than knitting yarns which were anything other than 100% wool so buying yarn *was* buying wool. I’m trying to re-educate myself but it isn’t coming naturally.

LikeLike

Fantastic, fascinating post! And the woollen fabrics are a revelation..

My grandmother and great-grandmother called all yarn wool, because wool yarn was all they ever bought. I imagine the same was true for others who were knitting in the early 1900s, When first taught to knit by my grandmother I made the same error but quickly learned to call ‘wool’ yarn unless it really was wool. A quick check with my family and they say I’m as likely to use a fibre name (e.g. Merino) or brand name (e.g. Ultra, Zephir) as say yarn. Just to add to the .confusion!

LikeLike

yes, yes, yes! Reminds me of when I did a guessing game with my school knitting club on what different yarns were and what animals or plants they might come from. The kids had a blast – with loads of ooos and ahhhs about silkworms and camel and seaweed and of course, sheep. (Had to disappoint one little girl who suggested lion’s mane). A couple of weeks later, a man from the guild came in and asked a similar question – they all put up their hands with their somewhat exotic answers and he said no to them all, except sheep and alpaca, leaving them very confused. Which goes to prove the difference in understanding between yarn and wool and how I wish he’d emphasised that difference to the bewildered children.

LikeLike

Extremely interesting, and you’re quite right about ‘yarn’ of course – and can I just say thanks for the beautiful images too? I love, love, love old textile sample books – sigh…

LikeLike

Guilty as charged on the wool instead of yarn front, it’s a hard habit to break. I do try to remember to make these distictions mind as in my world of spinning and feltmaking the word wool could be used (I think legitimately but creating further confusion) instead of the words fibre or fleece when describing that which is shorn from a sheep.

LikeLike

How funny, I never noticed that yarn shops are called wool shops in Britain. I guess I’ve avoided the whole issue by just calling them knitting shops – so I’ve never been accused of using Americanisms (which come naturally, seeing as I’m American).

LikeLike

I was just thinking that I tend to refer to knitting shops – mostly, I think, because there’s so much more than yarn in my local :) I try to use yarn when referring to what I’m knitting with if it isn’t wool (which it sometimes is).

LikeLike

I grew up (in Yorkshire, of all places) using ‘wool’ as the catch all term for things one would knit with, and most of it in those days was in fact hideous squeaky acrylic in unlikely colours. Now I say yarn without thinking, as it does, as you point out, make *much more sense to do so*. I have even become quite evangelical about it. However, my mother still thinks it’s a strange southern affectation…

LikeLike

As a new follower may I say how much I am enjoying your writing and the results of your research. As a felt maker I always use the word fibre rather than wool. I do work mainly with wool but also work with Alpaca, silk and at times synthetic fibres. To me wool is the natural fibre that grows from the skin of the sheep.

LikeLike

I’m a Brit who says yarn because it is correct. I don’t care about funny looks, I’m used to those ;) I like the word yarn :)

LikeLike

This reminds me of the mostly Texas propensity to refer to all soda as Coke.

‘You want a Coke?’

‘Sure, thanks.’

‘What kind? I’ve got Coke, Sprite, orange, and Dr Pepper.’

LikeLike

Yes! This phenomenon drives me nuts! It is also prevalent in other countries where Coke is the defining brand of soda.

LikeLike

This is also true in Kentucky. When my family moved here from Wisconsin when I was eight, I remember being terribly confused–we always said soda.

LikeLike

True for my Tennessee childhood as well! Every soda was called a Coke. (I just cringed typing the word “soda”.)

LikeLike

You are funny. I am in complete agreement about the usage of the word wool. It should be used for wool and not yarn and not garments pretending to be wool.

LikeLike

Very interesting post, thank you. Especially the last paragraph, which is absolutely correct!

LikeLike

Most people don’t really know the difference between different fibres. My other half assumes that all wool is scratchy thanks to his childhood and many assume the word wool to mean thick and warm and are surprised when you point out that the expensive wool suit that is actually fine and cool is indeed made of wool. These industry brand names just add to the confusion – who can possibly keep up? Far easier to throw your hands in the air and call everything by a generic term, which is what the word wool has sadly come to mean. Since learning to knit only a couple of months ago I’ve noticed that I’ve pretty much dropped the word wool from my vocab – it’s now more likely to be “merino” or “mink-cashmere blend” than something as simple and non-understood as “wool”.

Growing up in Australia, the world wool always meant quality. And it also meant sheep. You’ve touched on the Woolmark issue before – I’m wondering if there isn’t a need for a new brand that does what the Woolmark started to do before it got misappropriated. And since the Woolmark brand was always associated with “Pure New Wool”, perhaps we need something that works for blends too. Something along the lines of what they do on shoes where the little symbols show you instantly which part of the product is man-made and which part leather…

OK, rambling now so time to go

LikeLike

Actually, the Woolmark brand had variations for blends. It was to do with the inversion of the colours on the logo, or something, I think.

LikeLike

Here in Canada I find it is also common for people to say “wool” when they actually mean “knitting yarn” in the generic sense. Even more interesting, I have met people from Newfoundland who take it a step further and say “homespun” when they mean “knitting yarn”. Confused the girl from Ontario for a bit, they did.

I enjoy the content on this blog immensely, by the way. Very thought provoking, with lovely photography to boot.

LikeLike

You are right and you open my eyes. The main retailer here is “Planète Laine” whereas I suppose it should be “Planète fil”… Nevertheless, I thank God it exists !

LikeLike

Now I know why I was always getting such strange looks! I’m an American ex-pat living in Scotland and a fairly new knitter. A friend of mine was visiting from the States and taught me the basics. I used to always say ‘yarn’ but have slowly started saying ‘wool’ to avoid strange looks. Well now it’s back to ‘yarn’ full time, unless of course what I mean is ‘wool’!

LikeLike

My wife who lived in England as a child and later as an adult calls all yarn wool. I’m the primary knitter and must do some things in acrylic yarns was they have to be machine washable for charity. I, in the US would never call cotton or acrylic wool and at first was schocked that my wife did. I’ve gotten used to it.

LikeLike