Writing of the worn and mended Fair Isle sweater that Shetland knitter, Doris Hunter created for her fiancé, Ralph Patterson, who spent four years in a Japanese POW camp during the Second World War, editor Sarah Laurenson states: “Ralph’s sweater is much more than a physical object. It is a site of personal and political meanings containing traces of world events and the lives of individuals.” Sarah’s astute remarks on this incredible piece of knitwear speak much more broadly to the content of the wonderful book she has recently produced with the Shetland Museum and Archives. In Shetland Textiles: 800 BC to the Present we discover the intriguing stories of creative, enterprising, and brave Shetlanders like Doris and Ralph within the many cultural and economic contexts that make Shetland textiles so unique. Drawing on the knowledge of curatorial staff of the Shetland Museum, academics and researchers from several Scottish Universities, as well as a wealth of local expertise, this book is an important testimony to the significance and impact of Shetland textiles worldwide.

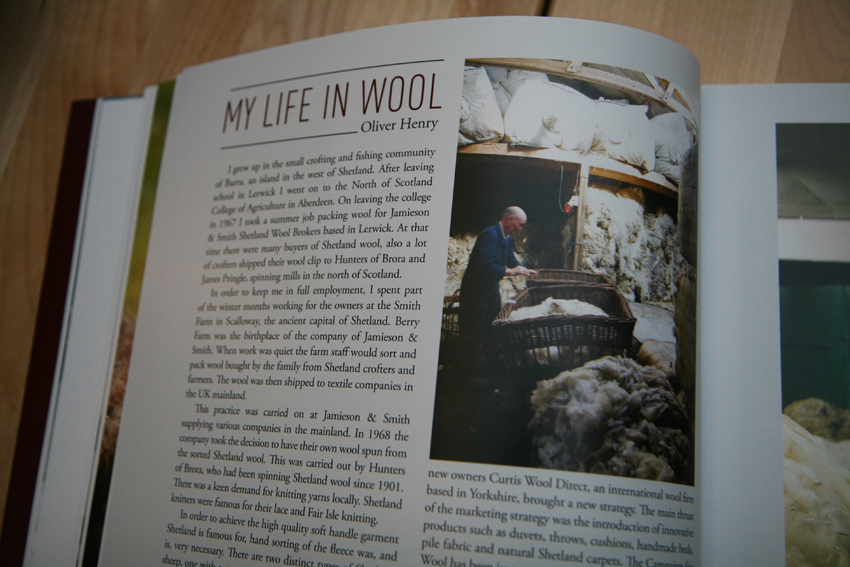

The crucial factor shaping the production of Shetland textiles from the Mesolithic to today is of course, the wool grown by its native sheep. A fabulous piece by Elizabeth Johnston introduces us to some of Shetland’s earliest examples of woollen textiles, while other sections of the book explore the the effects of the landscape on the development of the breed, alongside the realities of keeping a flock, and working with wool in Shetland.

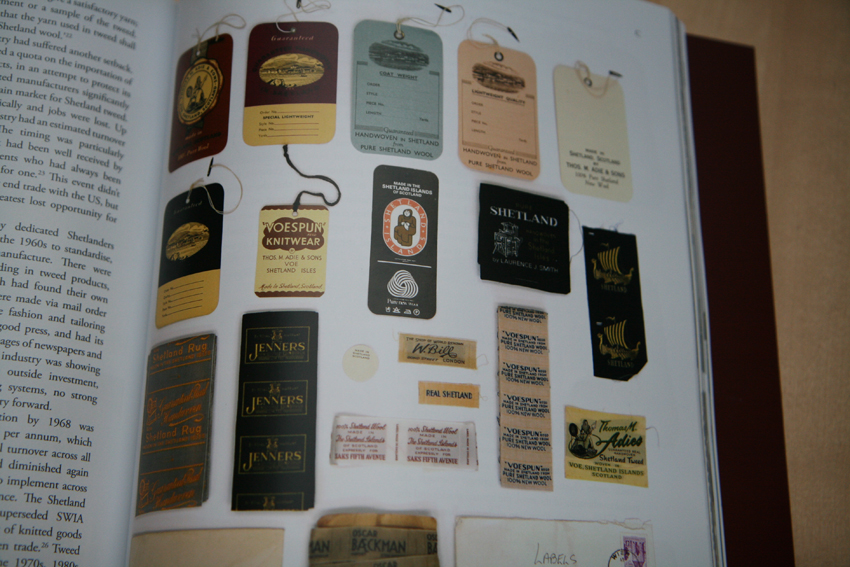

We learn that there are 57 names in Norn “specific to colours and patterns in sheep,” and gain insights into what makes Shetland “oo”, as a fibre, so very distinctive. Other things make “Shetland” distinctive too. Unlike, say, “Harris” tweed, (which refers to cloth woven on the island of Harris, but whose provenance is yarn spun from the fleeces of many different breeds and crosses, who may be raised in many different locales), “Shetland” is unique in its breadth of reference: to a particular group of islands; to the name of a particular breed of sheep; to the fibre those sheep produce; to the yarn spun from that fibre; and to the cloth, knitwear, and other manufactured products that are created from that yarn. Unlike “Harris” (an island ‘brand’ now famously trademarked and protected by national regulatory bodies), the broader resonances of “Shetland” ironically meant that it failed to gain the same protection. According to Sarah Dearlove in her important chapter on Shetland tweed, “the word “Shetland” and its use in the woollen industry in general has been the islands’ achillles heel.”

And yet, although the cachet of terms such as “Shetland” and “Fair Isle” means that they are frequently exploited, in some senses that very exploitation has also ensured their continued prominence and visibility within the textile industry. As Sarah Laurenson puts it: “histories of Fair Isle knitwear have to a large extent been shaped by marketing stories which do not necessarily fit with with the ideas and identities of people in Fair Isle and throughout Shetland. However, these stories have driven the commercial success of the style. Without them, there would be no Fair Isle knitwear.”

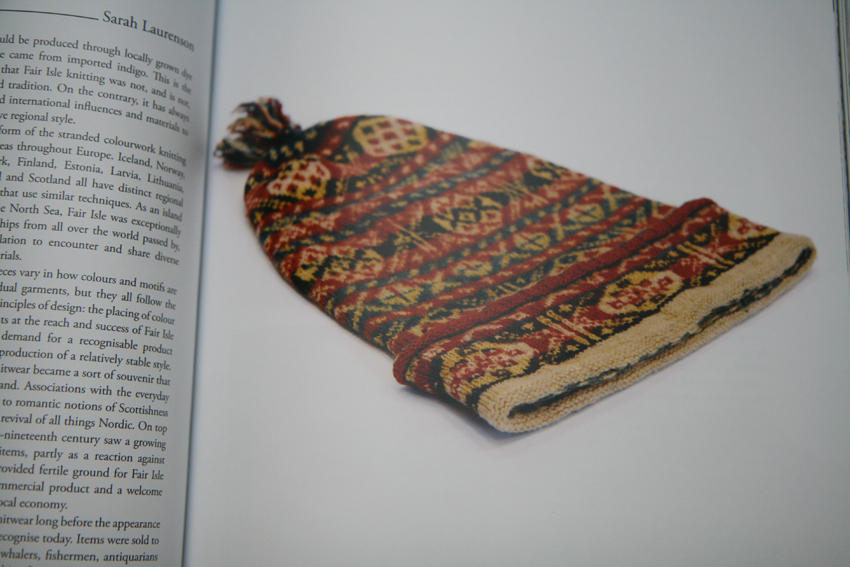

(early Fair Isle kep. Shetland Museum and Archives)

Shetland textiles are truly spectacular, and the book includes discussion of many important pieces, now housed in the collections of the Shetland Museum and Archives. There’s a great discussion of the incredible lace garments created by enterprising Lerwick hairdresser, Ethel Brown, and anyone who has seen Jeannie Jarmson’s prize-winning rayon tank top (depicted above on the book’s front cover) will not be surprised to learn that she hurt her hands in its making. Yet though these showstoppers are breathtaking examples of what makes Shetland textiles so special, it is also refreshing to read chapters focusing on the everyday. This is the forté of Carol Christiansen (curator of textiles at the Shetland Museum and Archives) and her sections in the book are genuinely illuminating. You’ll learn about the careful reconstruction of the woollen garments worn by the “Gunnister Man” by Carol and her team, revealling “crucial evidence for how early modern clothing was made, worn, and mended.” And while we are all familiar with the beauty of Shetland lace and colourwork, few are perhaps aware of the unique graphic appeal of the “taatit rugs”, which Shetlanders created as bedcovers and wedding gifts from the Eighteenth-Century onwards.

Building on the book’s wealth of original research is Ros Chapman’s piece about Shetland Lace. Her chapter effortlessly mingles intriguing documentary evidence with tantalising anecdote: “there was even an exhibition of Shetland knitting held in a Philadelphia department store containing a reconstructed croft around which knitters, ponies and sheep exhibited their uniqueness.” Ros’s lively chapter is merely the tip of the iceberg of a wonderfully thorough research project into the history, significance, and practice of Shetland Lace knitting. She is clearly going to produce an important book which I’m already looking forward to reading.

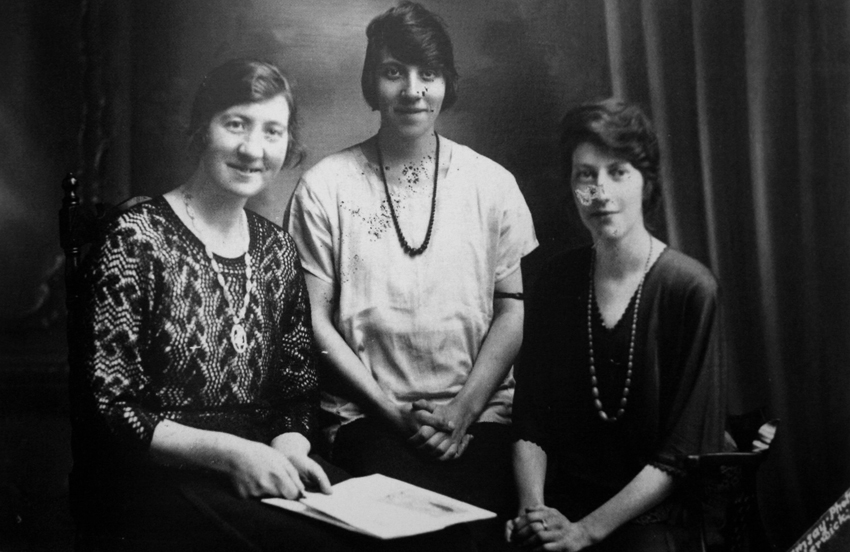

(Teenie Williamson (left) in a hand-knitted print o’da wave jumper)

Shetland’s knitters are, of course, at the heart of this book, and form the focus of Brian Smith’s and Lynn Abram’s contributions.

As Brian Smith puts it:

“It is important to remember, and easy to forget, that the people who knitted those tens of thousands of stockings and mittens, as well as performing other chores in and out of the home were Shetland women. It was an “honest man’s daughter” who came to Bressay Sound in 1613 with her knitting and got assaulted in the process; it was women who knitted the “Zetland hose and night caps” that Dutchmen were still buying there two centuries later; Shetland’s land rent was being paid from the women’s hosiery in 1797; they created the stockings and gloves presented to the Queen and Duchess of Kent in 1837; the “hose, half hose, gloves, mittens, under waistcoats, drawers, petticoats, night caps, shawls &c &c” in Standen’s Shetland and Scotch warehouse in 1847; and the Shetland goods on show in the Great Exhibition in 1851. And little cash they got for their pains.”

(Sketch of a Shetland knitter by Samuel Hibbert (1818)

Brian and Lynn’s chapters unfold carefully researched, well-written, and nuanced narratives about the economic realities of Shetland women’s lives, and the part that knitting has played in shaping them. All of us who enjoy our knitting as a stimulating or relaxing leisure pastime should read these chapters to gain insight into what it really meant to be a knitter in Shetland.

Brian’s chapters unpack the truck system (by which Shetland knitters were paid in goods rather than cash), which lingered on in Shetland well into the twentieth century. His account of the effect of collective action by the Shetland Hand Knitters Association, which was developed under the same post-war influences as the British Welfare State, is particularly interesting (and heartening).

Lynn’s piece reveals the wide variety of ways in which Shetland knitters used their own enterprise to support their families in response to extremely challenging social and economic conditions. “We were more or less financially secure” recalled crofter Agnes Leask after purchasing a knitting machine in the early 1960s, “as long as I could churn out about a dozen jumpers a week.” Lynn’s chapter (as much of her work) is extremely important in the way that it suggests the public and social resonances of a craft which is too often regarded in narrowly private contexts. “Hand knitting,” writes Lynn “was far from a domestic activity undertaken by women in the privacy of their own homes. In fact Shetland knitting created social networks and . . . relationships which aided women’s survival in the face of economic crises, personal loss, and the vagaries of living in these islands.”

As well as providing a rich overview of Shetland textiles and the history of their production, the book also introduces us to some of Shetland’s most talented contemporary makers and artists – Hazel Tindall, Emma Blain, Ella Gordon, and Donna Smith – all of whom are experts in their fields. These interviews suggest how Shetland textiles not only have an inspiring present, but a very bright future, a fact celebrated by Jimmy Moncrieff in his foreword to the volume.

I suppose I should mention by way of a disclaimer that the people mentioned in this post, who created and contributed to this wonderful book, are my good friends, colleagues and acquaintances. You would perhaps be very surprised if I didn’t like this book. But then I would be very surprised if you didn’t like it either.

If you buy one book about textiles this year, make it this one.

Sarah Laurenson, ed., Shetland Textiles: 800 BC to the Present (Lerwick: Shetland Heritage Publications, 2013)

ISBN 978-0-9572031-3-6

All images in this post are the copyrighted property of the Shetland Museum and Archives and are reproduced with their permission.

Wouldnt it be nice if it was taught in the schools too. History of textiles should not be limited to just a few people. Art History tells so much about people and there resilance in hard times and how they handed down patterns from one generation to another says much about how we must preserve these talents. thanks for history lesson.

LikeLike

If knitting was taught at school I feel this book would be on the reading list. It sounds wonderful. Now to make some room on the shelves to buy it.

LikeLike

Kate, your book reviews are always so great! I, too, ordered one and am eagerly awaiting its arrival for a good winter’s read. Thanks again for sharing such wonderful books.

LikeLike

Kate, thank you so much for sharing all the interesting information that you so often do. I love knitting and reading about its history. Your blog is my favorite, you are so knowledgable in your craft area and your love for it it contagious.

Sincerely, Lynn

LikeLike

My kind niece gave me this for Christmas, a beautiful book. One of the Shetland lace designs is the pattern one of my daughters knitted for her exhibition piece as a textile conservator. Stunning, so delicate and perfect.

LikeLike

Your review has done justice to this beautiful and interesting book. It’s one I will value forever and read many times. I look forward to Ros’ history book also!

LikeLike

Yup, over the edge :) I just ordered it………..din’t even think about it, just ordered it! Should have done so sooner but there you are! Thank you.

LikeLike

I carried mine home with me after Shetland Wool Week (I think it was the heaviest single thing in my luggage!). I haven’t had time to sit down and start reading it, but your review makes me want to make the time!

LikeLike

Your post has put me over the edge also, way over here in Ithaca, New York. Thank you!

LikeLike

I have been thinking about ordering this ever since it came out. Your post has pushed me over the edge. :-)

LikeLike

I love the vest/sleeveless top on the cover of the book.

LikeLike

Teenie Williamson’s sweater is WONDERFUL.I love it, and I was surprised to see the stitch pattern; I just knit a stole with it and had no idea it was a Shetland lace pattern! I suppose not all patterns can include historical notes, but a girl knitter can dream…

LikeLike

Great post. Ordered my copy late last night. This morning, my grandson appeared wearing the Fair Isle cardigan that his father wore, knitted by my husband’s mother about 30 years ago. This is the 5th child in our family to wear it. She was not a Shetlander, but used the proper wool from Jamieson and Smith. Also today my 5 year old granddaughter knitted her first 3 rows–she is a natural, unsurprisingly.

LikeLike

Thank you for the rewiew. I really want to read this book and have to order it now.

The grass looks always greener on the other side of the sea. Ulrika from Göteborg, Sweden.

LikeLike

Such an interesting post, Kate.

LikeLike

What an amazing post….thank you, Kate. It strikes me so often, the story that is contained in a hand-crafted piece. I know my very DNA is ingrained in everything I make….along with that of the sheep/caterpillar/farmer/spinner/etc.. It is all there and it imbues the FO…

Your perspective and your beautifully crafted posts are such a pleasure. Many thanks!

LikeLike

This is indeed a fabulous book and was a perfect Christmas present for me. We got our copy for £20, with very reasonable postage, from the Shetland Times. I highly recommend both the book and the bookshop.

LikeLike

I agree Polly, I also received my own copy at Christmas highly recommend this book, and the shop as well .

LikeLike

Wonder what garments lasted all those hundreds and hundreds of years, and how? Felt 1000s years old was discovered in the Altai mountains but only survived because frozen in permafrost. Love that textiles are transitory in their lasting on the planet, and the dust returns back to the earth. Tantalising review btw :)

LikeLike

Kate – this looks fascinating – but, now you must make us a design to match the fantastic fairisle tank/T on the front cover!

LikeLike

I have just submitted my order to the museum and will be biting my nails until the package makes it across the Atlantic! Does anyone know if the book contains information about the wonderful knitter, Annabel Brey (possibly Bray)? I met her in Shetland in 1985 and have a staggeringly beautiful sweater than she knit.She worked in a beauty parlor at the time.

LikeLike

Quite a number of people are conspicuous by their absence, but I guess it was impossible to include everyone. Annabel Bray truly was an inspirational Fair Isle knitter whose work I greatly admired.

LikeLike

Hazel – Thank you for responding! If you’d like to see a pic of the sweater with its partnering cap, I’ll gladly send you one. Mrs. Bray repeated a lovely “K” in the borders of both, which was a sweet surprise!

LikeLike

Kerry, it would be lovely to see a photo. Annabel was a member of Shetland Guild of Spinners, Weavers & Dyers (before I joined unfortunately) so I am sure they would be interested to know the story of one of her pieces of knitting.

LikeLike

Hello Hazel – Yes, I’ll send you some photos of the sweater and hat, inside and out. If you send me an email message at kjtucker1@gmail.com, I can attach them to a response message. All the best.

LikeLike

I got my copy on its release when I was in Shetland, and got to arrange a brief acquaintance before I needed to ship it home (my luggage being at risk of overweight). It just arrived here last week, and I look forward to being past the current spate of deadlines so I can become better acquainted. Thanks for your overview, Kate.

LikeLike

Nice. I had to go buy it. My pay pal account is very tired.

LikeLike

I received this book as a gift from my partner for Christmas. I agree with what you say: this is a great book. It contains a huge wealth of information, and it is possibly the best book in my collection. If only there would be a book like this about every aspect of knitting & textile heritage… *gasp*

LikeLike

I have loved reading and rereading parts of this book.

LikeLike

How interesting…I love the history of textiles and I just ordered a book on the history of felt and the felt industry. These stories are so important for us to know about.

sounds like those women were slaves to the knitting needles for a long time.

A DOZEN jumpers a week? Wow! Even on a machine that seems like a lot!

I will definitely look into this to have in my library. Cheers!

LikeLike

I got the book the day it came out. Around $80 to the US. The pictures, quality and information made this well worth with the cost.it is a serious textile book and absolutely beautiful. I am not sure if this was addressed in the book, but do present day Fair Isle designers use computer programs to manipulate patters, color and designs.?

LikeLike

It looks like an well-researched, informative book that encompasses an astounding history. Definitely a special book to add to the library.

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks for the review! I’m not just a knitter; I’m also a librarian. This would be a good addition to our collection…available in the US? In the future?

LikeLike

I purchased the book in November 2013 & i find it a great read. It did cost me $93.00 cad with the exchange but still well worth it with beautiful pictures & text.

I must say though, Its interesting how Shetlanders don’t like the rest of the world using the name/term ”Shetland wool for our yarns & knitwear” that we produce here in North America but they were quite willing to take the money from Exporting the said named pure bred sheep to North America….you Scots can’t have it both ways you !

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the lesson. Wonderful information and I now have the book at the top of my list!

Best,

Sheila

http://sheilazachariae.blogspot.com/2014/01/diy-shawl-pin-with-buttons.html

LikeLike

Oh my goodness, this looks fascinating. Thanks for the comprehensive review!

LikeLike

Very strangely there is no mention of Margaret Stuart who took care of her knitting company, wrote books and also took care of the Shetland Museum.

LikeLike

This has been on my list (the last time I was in Shetland I stayed with someone who made taatit rugs – fascinating). Now I know I have to do something about getting it off the list and onto the great heap of books by my bed. Thanks for posting – it really does look irresistible!

LikeLike