I often receive requests for copies of features and articles I’ve published. Hard copies of individual magazines can be hard to find, and many publishers don’t make back issues readily available in digital formats. So, in the spirit of open access, I’ve decided to “reprint” some of these pieces here, where everyone can find them. This piece, originally published in Selvedge in March 2008, is one I’m asked about quite frequently. The work of Tabitha Kyoko Moses is always thoughtful, and thought provoking and she probably remains my favourite artist working with textiles in any medium. I think it is her very particular combination of precision, beauty, and discomfort that I like so much. I was very happy that Tabitha also enjoyed my piece when it was published, and I urge you to explore more of her work on her website.

========================================================================

GOODBYE, DOLLY

(Annies Room, the shrine under the streets of Edinburgh’s Old Town)

“We have naught for death but toys” W.B. Yeats

Several hundred feet beneath the streets of Edinburgh’s Old Town, a doll sits in a cold, dark room. The tattered plaid she wears is showing signs of age. Her limbs are dirty and her hair is white with dust. Gathered around her are hundreds of companions. There are Barbies and Beanie-Babies and several Raggedy-Anns. Stuffed animals jostle alongside plastic infants; painted wooden soldiers smile up at porcelain princesses. What are they, this dusty jumble of toys piled five feet high? What brought them here together? In 1992, Japanese psychic, Aiko Gibo, visited Edinburgh’s re-discovered city-beneath-the-city and reportedly felt the tugging hands of a girl abandoned there to die in a plague year. Gibo comforted the restless ghost with the tartan doll, leaving her a curiously nationalist playmate. Since then, numerous visitors to what is now known as Annie’s room in Mary King’s Close have done the same. What are we to make of this shrine, this spontaneous doll-memorial to the ghost of a girl no-one remembers? Are we moved or repelled by Annie’s room?

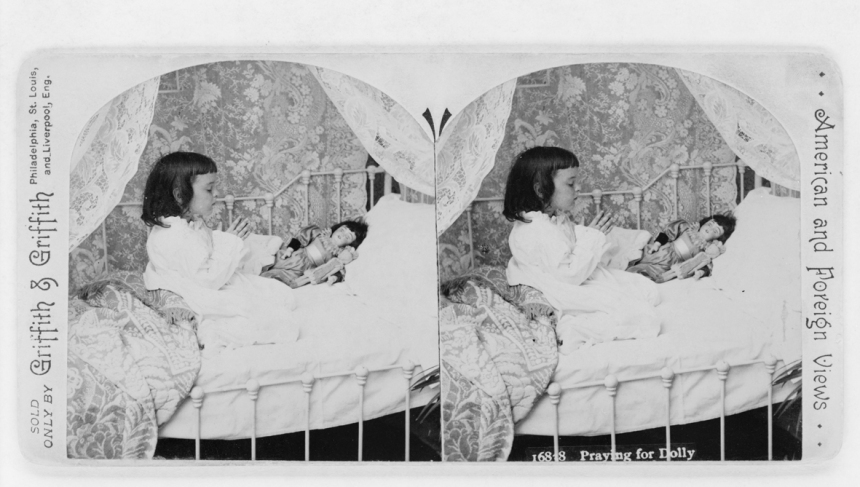

(“Praying for Dolly” c.1900-1910)

All cultures mark the boundary between life and death with imitative rituals. Dolls are familiar figures in funerals across time. The tombs of the ancient dead are filled with effigies whose assumed purpose ranges from the talismanic to the admonitory. Children use dolls to play at death, mimicking grief and burial. Dolls, indeed, look like death. It is not just that in them we find an appropriate figure for our mourning, but, in their cold imperturbability, they seem like corpses themselves. This doll-corpse association is explored in Andrew Kötting’s playful and serious project, The Wake of a DeaDad (2006). Intrigued by his reaction to his father’s corpse and memory, Kötting reinvented several imitative rituals, which included inviting responses to photographs of his dad in stages of life and death; laying himself out as mock-corpse and paternal offrendas in the Mexican Day-of-the-Dead; and creating an enormous inflatable DeaDad doll with which he lived and travelled for several months.

(Andrew Kötting The Wake of a DeaDad (2006)

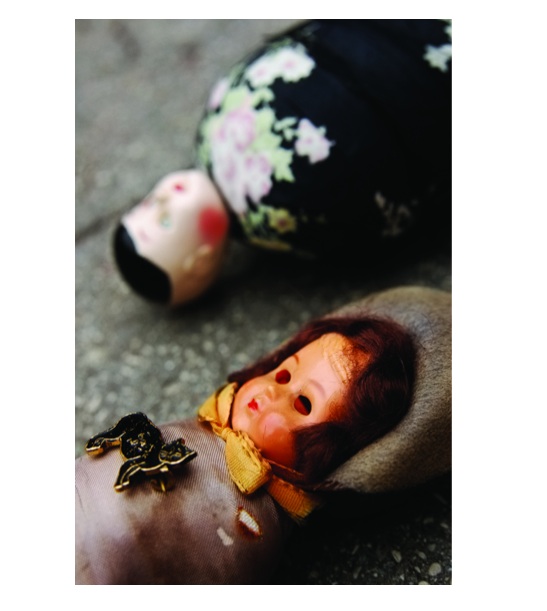

With a different sort of wit and tenderness, Tabitha Kyoko Moses also explores the humanity and deathliness of dolls. Over the past few years, Moses has amassed an eclectic assortment of doll-objects from charity shops and jumble sales “I wasn’t interested in a particular genre of doll,” she says, “or in creating a collection or a history. But suddenly I discovered I had a lot of them. It was almost as if they found me.” The dolls that “found” Moses are those that are most “lost”: blemished or dismembered, loved or tortured to the point of collapse. Inspired by a mummified girl she encountered during a residence at Bolton Museum, Moses initially began to re-fashion the dolls as consolatory gifts for this long-dead and lonely child. But, perhaps like the toys in Annie’s room—gathering dust and becoming, together, something more than themselves—her dolls began to take on a material life of their own. In a process of wrapping and nurturing she compares to “laying out a dead body” Moses swaddles her dolls in lagging, plastic, printed cotton lawn, stiff leather, string, and human hair. A doll whose jolly bonnet and rosy cheeks form a startling contrast to her eye’s bald sockets is fondly adorned with a manx-cat brooch, suggesting both completion and absence. Some of the dolls have the cosy air of children sleeping. Others appear to be slightly disgruntled, uselessly struggling against the fabric bundles in which they find themselves enclosed.

(Tabitha Kyoko Moses, “The Dolls” (2004) dolls, fabric, plastic, thread, human hair, bits and bobs. Photography by Harriet Hall and Alexandra Wolkowicz).

(Tabitha Kyoko Moses, “The Dolls” (2004) dolls, fabric, plastic, thread, human hair, bits and bobs. Photography by Harriet Hall and Alexandra Wolkowicz).

The fabric wrappings are crucial to the new life that Moses lends her dolls. These textiles are both ornament and container: the dolls’ soft coffin and their decorative memorial. Moses binds a startled bride wearing full wedding regalia in dark linen.

(Tabitha Kyoko Moses, “The Dolls” (2004) dolls, fabric, plastic, thread, human hair, bits and bobs. Photography by Ben Blackall)

In her black shroud she becomes a figure of arrested potential, conveying the ritual proximity of marriage and death. Moses further excavates the deathliness of her dolls with the use of x-ray photography.

(Tabitha Kyoko Moses, The Dolls. X-Ray (2007))

. . . A light-box image of the bride reveals her to be pierced with several pins. She now resonates with murderous curiosity, internal anguish, guilt, and fascination. For who, in moments of dark childhood fantasy, has not killed their dolls?

(“Private Investigations lead to . . .” (1907))

In their lovely, yet deeply disturbing ordinariness, Moses’ dolls and textiles recall the partially-covered corpse in Wallace Stevens’ poem The Emperor of Ice-Cream:

Take from the dresser of deal,

Lacking the three glass knobs, that sheet

On which she embroidered fantails once

And spread it so as to cover her face.

If her horny feet protrude, they come

To show how cold she is, and dumb.

(Wallace Stevens, “The Emperor of Ice-Cream”. Harmonium (1922) )

Stevens’ corpse is an object of the everyday. In her cold immobility she reminds us of death’s easy finality. Yet, like Moses’ cared-for dolls, she also suggests the mute compassion of the world of things. We feel the careless weight of her hands on the well-worn dresser; her fingers’ quick movement through the stitches of the modest cloth that now decorates her countenance. The dead woman cannot speak, and yet the meanings of her selfhood are silently carried to us in that fantail-embroidered sheet.

(Tabitha Kyoko Moses, Untitled (2006). cotton fabric, sawdust, human humerus bone, various threads, hand embroidery. Photography Ben Blackall.)

In Untitled (2006) Moses uses stitch as a communicative medium between life and death. These dismembered limbs, with their immaculate embroidery, are textiles of breathtaking beauty. Yet out of the gorgeous doll-things protrude human bones. Doll and corpse become one in objects that are both compelling and repellent. Moses’ embroidered calico, fashioned with such skill and care, lends respect and tenderness to the bone, and the bone in turn enhances the meanings of the fabric with its own brand of the grotesque. In complete contrast to Cindy Sherman’s doll-art which, in the public glare of her camera, strives unsuccessfully to be poignant as well as disgusting, Moses’s dolls achieve this by expressing themselves intimately, stitching their audience up with whispers.

So, to return to where we began, perhaps Tabitha Moses’ dolls tell us something abut how to feel in Annie’s room. What’s interesting when one begins to look closely at the piled-up array of gifts in that dark tenement is their different associations. Some have been left with evident care (a pricey bébé) others with apparent thoughtlessness (a screen wipe). So many of Annie’s toys seem just misplaced or random: plastic binoculars, a Westlife CD, an enormous grinning bear. Together, though, these things have transformed a space that is supposed to be terribly spooky and lent it a spectacular ordinariness. Annie’s room has a stark materiality in which there is a pathos that exceeds, or defies, the uncanny. Like Tabitha Moses’ dolls, Annie’s too are part of the kindly world of things.

©Kate Davies

Grateful thanks to Tabitha Kyoko Moses, and to Lisa Helsby of Mary Kings Close.

Originally published in Selvedge March 2008. Revised February 2014.

I actually found this article very thought provoking. After much thought, I have decided that art can be very much more disturbing than death in it’s macabreness.

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading this, it reminded me of my own childhood.

I actually have a photo of myself as a child, pretending to be an evil witch and killing the babies (dolls). I also once ripped the head off my sister’s favorite Barbie doll in a “murderous” rage ;) We sometimes pretended our Barbie dolls were having sex, and once we cut a doll’s hair off and painted her green to pretend she was an alien from outer space.

But I never did anything “mean” to my favorite dolls.

LikeLike

I have. And you have freed me from 54 years of feeling that it was only me. Thank you.

LikeLike

Art comes from the soul, often unbidden and automatic, often reflecting the dark inner places that need expression. I was immediately reminded of my favorite artist, Frida Kahlo, whose painful life and difficult relationship with her less talented husband, Diego Rivera, produced evocative paintings, which only after her death people are understanding. “X ray” in particular, reminded me of Frida’s representations of the sugar skulls and skeletons of “Dia de los Muertos.” “Untitled” immediately brought my mind to Frida’s “My Birth,” with Frida’s head hanging askew as she births herself. Death is a part of life.

(Do watch Amy Stechler Burns’ “The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo” if you have not already).

Textiles, from the silk gowns of the past, to the lowly sock knitted from necessity, (in contrast to valued paintings and other art forms), do not stand the test of time, but are nevertheless valued pieces of art. Adding a face to a three dimensional object that will have its end when tossed in the trash eventually (think “The Velveteen Rabbit) makes the demise pretty eerie.

Thank you, Kate, and how nice that “Selvedge” does not have a copyright that disallows you from publishing this fascinating piece on your blog!

LikeLike

Great essay.

It’s thrilling to see the surface ‘prettiness’ and ‘cuteness’ of dolls blown open for deeper investigation, and your writing and the work of Tabitha Moses offer a rich guide to our complex relationship with these objects. I love how you connect textiles and everyday objects with feelings and ideas around death and ritual, and propose so many thoughtful reasons why we might find dolls both attractive and repellent. I also love the broad scope of your discussion, and the connections you’ve made between the collective creation of “Annie’s Room” and works by Andrew Kötting and Tabitha Moses. What I love most of all is the strong thread of materiality that runs through this piece, starting with a textural description of Annie’s room and ending up with “the kindly world of things”. The same fascination with textures and materials which runs through this writing seems to me to feed into all your own work with textiles, enriching how we can think about them as specific sites of meaning, history and resonance.

I’d not seen Tabitha’s work before, but her doll series is amazing! The textiles and wrapping techniques used evoke ancient practices of embalming, and the figures of mummies or effigies – an idea emphasised by their placement in museum cases. Yet the doll faces – especially the arrested bride – seem strangely contemporary. It is a tantalising mix which makes the spectre of death more threatening and imminent.

I love that it is only through the X-ray process that hidden darknesses are revealed, including even the notion of pins being pushed into voodoo dolls in private moments of malice. Doll-play is a powerful place to explore relationships and feelings and to practice behaviour; including violent behaviour. But the fact that the violence in this case is hidden inside the linen wraps speaks also of the shame and taboo which surrounds such ‘child’s play’.

An aside – I recently came across some extraordinary photos of an abandoned doll factory in Spain:

http://scribol.com/urban-exploration/news-incredible-images-abandoned-doll-factory

it strikes me that your piece gives an extra level of thinking to the contemplation of these images which are again very eerie and textural, and which we cannot but connect the scattered broken doll parts with the spectre of our own inevitable, physical demise.

LikeLike

I had never made the connection between dolls and death before but as soon as you say it, it is obvious. A few years ago I unexpectedly came across the phenomenon of ‘reborn’ dolls. These are dolls that are sculpted and modelled to look exactly like real babies. You can send a photo of your baby to the artist who will replicate their features precisely. Sometimes people do this to remember what their children looked like as babies. Often, it’s done as a memorial to a child who died. I found it disturbing and freakish. Somehow Moses’s dolls in their shrouds feel like the appropriate antithesis.

LikeLike

Brilliant post. Thank you. Makes me think I should read my back copies of Selvedge more closely. Also highly pertinent to creative work I’ve been engaging in recently.

Am reminded of Margaret O’Brien’s character in “Meet Me in St Louis” burying her dolls in the yard after they’d died of terrible diseases.

Also someone recommended to me the novels of Sylvia Waugh, concerning the lives of “The Mennyms”; a family of life-sized rag dolls inhabiting a large house. Although aimed at older children, I’m totally enjoying the tale of their struggle to survive in our world whilst engaged to varying extents in the process of pretending to be human.

Interestingly the grandmother manages to contribute to the family finances by hand knitting garments exclusively for Harrods!

LikeLike

Fascinating, thought provoking piece, Kate. And this aspect of your blog … that which displays your intellect and unabashed curiosity, are why you are a “bookmark” on my desktop. Thank you for sharing it and for the links, particularly to Moses.

LikeLike

To each his/her own, I suppose. “For who, in moments of dark childhood fantasy, has not killed their dolls?” Not I.

LikeLike

Absolutely! Me neither. I really can’t understand this notion.

LikeLike

I have. Barbie dolls are not just for dressing up!

To ungracefully summarize Stephen King, for the same reasons we need fairy tales (the original, unsanitized versions), and horror movies – they provide a catharsis, so that we don’t need to turn our dark fantasies into reality.

LikeLike

prowling off with my whiskers and tail drooping…how can anyone abandon a bear? :(

LikeLike

“how can anyone abandon a bear?” – perhaps they weren’t abandoning it, they were giving it. Say, to a dead child, or the memory of one. Perhaps that was just what the giver needed to effect closure after bereavement.

Or perhaps they preferred to put the bear among friends to leaving it collecting dust alone on a top shelf or giving it away all by itself to a charity shop. You can’t tell.

That’s sort of what this kind of art is about, isn’t it? One bear can carry so many possible human stories, and wondering about them makes you think about your fellow human beings and what might be going in in their minds in a different way. It brings me back to one of my favourite sayings, “Be kinder than necessary because everyone you meet is fighting some kind of battle.” Surely that’s a good effect of art?

LikeLike

YIPES……….

LikeLike

An insightful and evocative article that hones in the artist’s ability to provoke thought by turning a familiar, comforting object into one that jolts one out of a one sided complacent view of the world.

While it may not fit everyone’s taste, it’s important, I think, not to overlook the embroidery in Moses’ piece “Untitled.” It is exquisite to the extreme.

LikeLike

Let be be finale of seem (seam?), indeed. Thank you so much for sharing this piece with us, Kate, and for the introduction to Annie’s Room, Mary King’s Close, and Tabitha Kyoko Moses’ brilliant work.

LikeLike

This is really creepy and fascinating. A bit uncomfortable, because it raises so many questions about our creativity and the power of it combined with our “imagination.” Thanks for the post.

LikeLike

What a wonderful article! Thanks so much for making it available to all of us. I found the not deliberate art as interesting as the intentionally made art.

LikeLike

Wow, this post is sudden & unexpected, bold & fresh and rather blew my socks off. Fascinating !

LikeLike

I thought it was fascinating. It reminded me of the memorials on the gate of the Cross Bones burial ground in Southwark: home to thousands of burials of the ‘outcast dead’ – local prostitutes who were buried in unconsecrated ground. It’s now a derelict car park with not a single marker to show that it was ever a cemetery, and yet over the years people have covered its gate with hundreds of home-made tributes – cds, flowers, poems etc – and made of it a shrine to all those unremembered women. Annie’s room seems to serve much the same purpose; a spontaneous remembrance for the unremembered. It’s both moving and creepy, in an awesome way, and so are the fantastic dolls. Thanks for the introduction to Ms Moses’ work! I shall enjoy looking at her website.

LikeLike

I love this post! I happen to still have 3 or 4 of my dolls that I cherished as a girl. I remember sucking my thumb and grabbing a dollie, feeling so comforted. I also have the doll my mum had made with a replica of her wedding dress. It was very common in the 50’s and before, to have one made for yourself.

Thank you for a very educational and lovely post.

Sheila

http://sheilazachariae.blogspot.com/2014/02/bonfire-wedding-blanket.html

LikeLike

I also find this depressing. These women seem to have some issues that need/needed working out. I’m sorry for them and don’t see why this even deserves an article; the women need counseling. I also don’t see what this has to do with knitting or textiles. I otherwise really enjoy your blog and love your designs. But this just doesn’t seem to belong. Then again, it’s your blog and you are free to write what you want.

LikeLike

I find this very depressing. Wouldn’t the poor broken dolls be better served if they were rejuvenated and donated to agencies who could pass them out to children with no toys?

LikeLike

Powerful stuff, thank you for sharing. Half way through reading this I thought ‘what would Truds think of this?’……my sister-in-law died four years ago. It was a spontaneous and ordinary thought. An affirmation of the connection to the great unknown. I love it when Art touches me in this way.

LikeLike