There have been some interesting questions in the comments on my previous posts about the Great Scottish Tapestry. Elaine and Deborah asked what materials had been used in the creation of the tapestry – well, the stitchers used Peter Grieg linen and Appletons crewel wool throughout. Terry asked why it was called a tapestry at all, given that strictly speaking it isn’t, which is an interesting question. I couldn’t find a direct answer to this, but speaking personally, my sense of it is that for the majority of folk who are not involved in craft, design, or the fibre arts, the word tapestry immediately suggests the Bayeux Tapestry, which is not woven either, but is similarly embroidered, from similar materials, in a similarly collaborative fashion. Perhaps its the public, narrative connotations of the word “tapestry”, derived from its associations with Bayeux, that have lead the project to be so described? Those who have been directly involved might like to add their thoughts in the comments below. And yes, I am aware of the Prestonpans and Diaspora projects, and am very much looking forward to seeing them both.

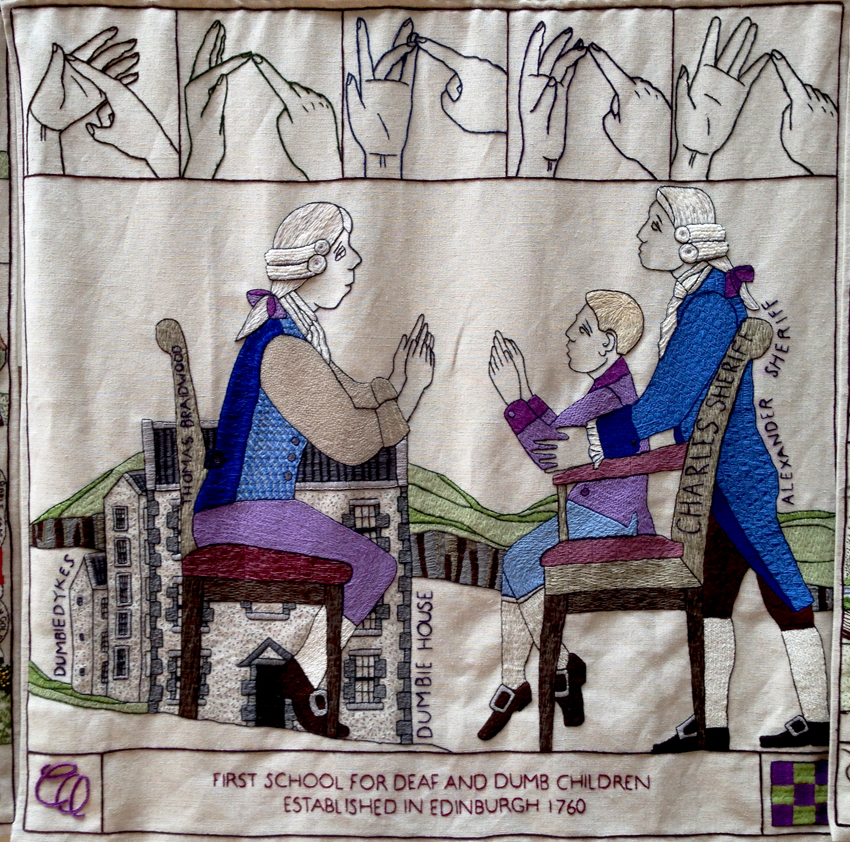

As I continue through my photographs of the tapestry, I find myself vaguely frustrated that there are things that I missed, or failed to record with a photograph, particularly in the eighteenth-century sections. . . but I suppose the tapestry’s richness, its inexhaustive nature, is one of the most wonderful things about it. Plus, I fully intend to spend time with it again when it comes to New Lanark in October. Regarding panel 64, which you can see at the top of this post, one of my academic interests many moons ago was the development of what we now know as sign language out of the “natural” philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment. I was particularly pleased to see a panel recording the pioneering work of Thomas Braidwood, who established the first school for signing in Edinburgh in 1760.

So here are some more tapestry highlights . . from my favourite period in Scottish history.

Panel 65: James Small and the invention of the swing plough. Love the neeps and kale. “The swing plough changed cultivation radically and by doing that it changed the world”

Panel 67: Edinburgh’s New Town. Auld Reekie’s familiar Enlightenment geography

Panel 70: Adam Smith Delighted to see Smith’s invisible hand . . . made visible!

Panel 73: Weaving and Spinning Loved this panel, stitched by Frances Gardner and Jacqueline Walters. The details of the lace shawl particularly killed me.

Panel 74: James Hutton’s theory of the earth the birth of modern geology.

Panel 75: Smoked fish I love how the figure of the fisher lass merges in with the landscape in this panel – that’s her striped skirt you can see in the photo. Finnan Haddies, Arbroath Smokies . . . nom.

Panel 77: Scotland and the drive for Empire I liked how this panel carefully represented the Atlantic Triangle as a commercial, profit-driven enterprise, with hideous human costs.

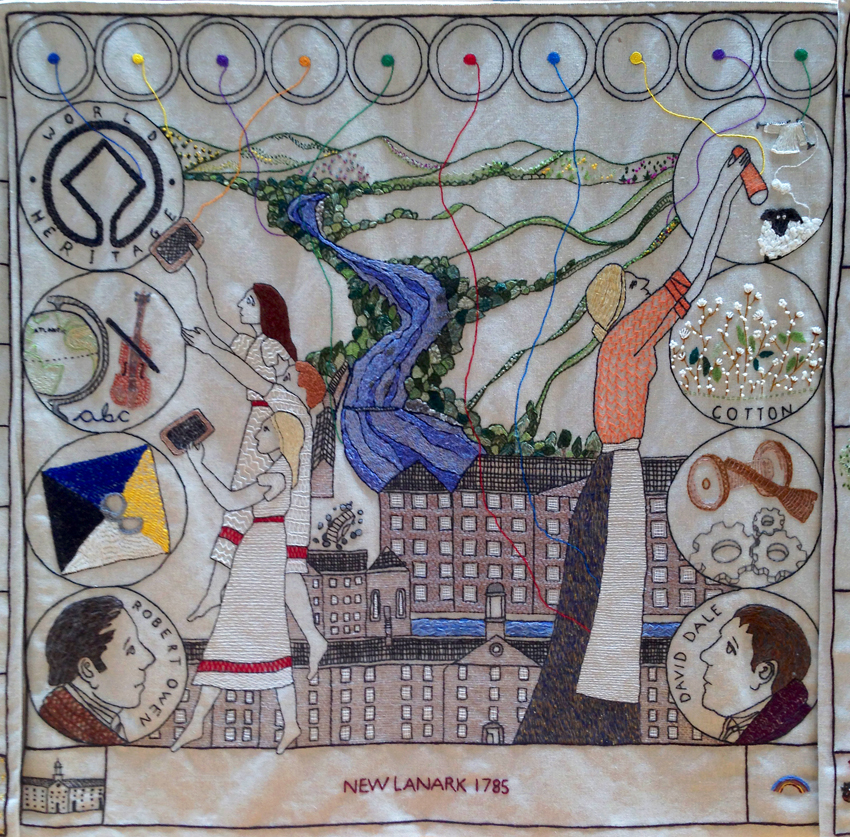

Panel 78: New Lanark Loved the Falls of Clyde, the silent monitor (I have one on my desk) and the way the figures of the dancing children echo their depiction in contemporary prints of the period. (In the eighteenth-century panels, I often noticed Crummy’s designs directly referencing contemporary prints and paintings.)

Panel 87: The Growth of Glasgow A truly wonderful panel, stitched by the Glasgow Society of Women Artists

Panel 90: Kirkpatrick Macmillan celebrating the modern bicycle’s 1839 wooden prototype

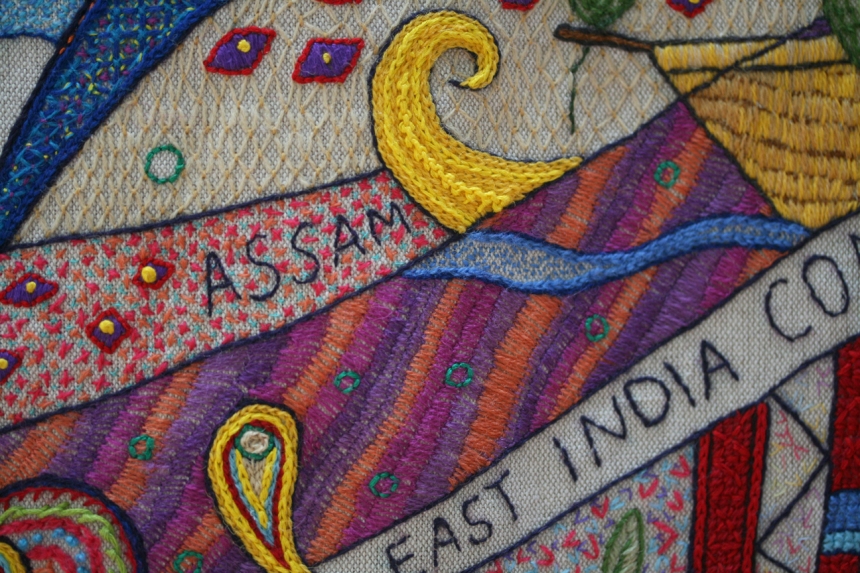

Panel 92: The Scots in India this richly coloured and beautifully detailed panel, stitched by Edinburgh’s Wardie Church stitchers, is truly a work of art.

Beautiful! and thank you for the photos so that I can admire this from across the ocean. Regarding the tapestry/embroidery question, I think that calling it the Great Tapestry of Scotland allows one to use the word ‘tapestry’ in its broader sense: that is, a work of art depicting all of the details, great and small, of Scottish life. As in “the tapestry of life.”

LikeLike

Wow!! This is Amazing!!!!

-Gertrude + Sly

http://GertrudeAndSly.com

LikeLike

Verdaderamente hermoso y un gran trabajo. Me ha gustado conocerlo

LikeLike

And by the way Kate Davies I have just spent rather a lot of money on the book which goes with the tapestry. You do realise that it is all your fault?!

LikeLike

Magnificent – the “lace shawl”! There is so much history in there.

LikeLike

speechless. the work, the preservation, appreciation, meanings, it’s all just beyond the beyond.

LikeLike

Thank you for the info on linen and thread! I am loving these posts, and look forward to seeing the tapestry in person in the coming year.

LikeLike

Thank you for your beautiful photography and for sharing this with those of us who can’t see it in person. The work is just stunning.

LikeLike

This is truly glorious to behold. I wish I could see it in person, but your sharing with us is wonderful!

LikeLike

Really beautiful tapestry!

LikeLike

These are just so amazing. Breathtaking.

LikeLike

Kate, your photography does you credit capturing this beautiful work. I love the detail and we can consider it more, perhaps than in person. However, I think to actually see it must be breathtaking, to appreciate the enormity of the project and to consider the contributors who must be, and rightly so, very proud of their work. Thank you for giving us an opportunity to have an insight to this beautiful piece. The invisible hand made me smile, but it is all very emotive, in some shape or form. Thank you.

LikeLike

Extraordinary. One could spend days staring at the detail. Thank you so much for sharing it.

LikeLike

Thank you so much Kate for sharing this absolutely wonderful art work! I am so impressed with each piece you are posting. Each sample is wonderful and full of rich colorful detail.

LikeLike

Kate, hope you don’t mind me suggesting here that for anyone interested in a discussion about when is a tapestry not a tapestry they might be interested in the following blog: http://dizziebhooked.wordpress.com/2014/06/02/week-13-when-is-a-tapestry-a-tapestry/#comments

Loving your photos of the Great Scottish tapestry, and can’t wait until I have a chance to see it in the flesh.

LikeLike

Oh my . This is so beautiful. I , like everyone else, would love to see it in person. Thanks for the fabulous pictures.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing and in so doing help “shrink” the world

LikeLike

I love the Hudon’s Bay square. I’m from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada where we just celebrated a major anniversary of the tough Scots who settled here. I really admire the workmanship that has gone into this project.

LikeLike

Thank you again, Kate. These have been my all-time favorite blog posts …. on any blog, anywhere! I am sharing them with my knitting group here in Virginia, and we are all enraptured. Such an effort, so beautiful and such a rare treat.

LikeLike

What a glorious treat! Thank you so much for sharing this! I have one question, though, what is “the silent monitor”?

LikeLike

It’s the four colored thing in one of the left rondels. It was something that was used to indicate how hard someone was working in the mill. (Kate please correct me if I have misstated this!) Here’s where I found out about it:

http://www.newlanark.org/kids/index2.html

What that doesn’t say is how the side was chosen. By an overseer or foreman? Can anyone clarify for us? Thanks!

LikeLike

I would have missed the connection and detail about Thomas Braidwood and the signing connection had you not highlighted the panel.

My grandfather, Edward Robert Abernathy,(scottish) was the superintendent of the Ohio School for the Deaf for 41 yrs. My father grew up there as well as my 3 aunts. I *wonder* if there was a connection, even just a small influence from such a history?

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing all these pictures and informations with us. It is definitely a masterpiece – all those details!! It is always a pleasure to visit your homepage.

LikeLike

Oh I love the Hudson’s Bay Company panel…I can see my neck of the woods!

LikeLike

oh you had fun!!

thanks for taking us with you

x-x-x-x-x-teri

LikeLike

Such gorgeous pieces

LikeLike

I recommend the Quaker tapestry in Kendal. Similarly beautiful work done by meeting houses over the uk and it even bore a new stitch, the Quaker stitch (I would have preferred something slightly more imaginative, but there you go). My favourite thing about it is that they chose to embroider onto wool instead of linen because it’s more forgiving of mistakes, which encompasses the Quaker ethic, for me.

LikeLike

How beautiful! I really love the detail of the spinner and the weaving. Thank you for sharing these photos!

LikeLike

These are s beautiful (including the last two posts) they truly bring tears to my eyes. How I wish I could see them in person. Thank you so much for these posts.

LikeLike