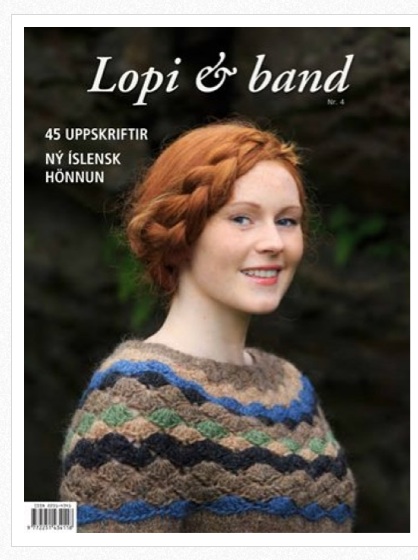

Today I want to share with you a conversation I recently had with Margret Linda Gunnlaugsdóttir and Ásdís Birgisdóttir – two of Iceland’s most important and influential designers of hand-knits. I knew of Ásdís and Linda’s work with the 1990s Icelandic magazine Lopi & Band, and was fascinated with their designs, which seemed really distinctive and innovative. I was particularly interested in Ásdís’s innovations with integrated yoke shaping (a design technique I was experimenting with at the time) and from Hélène‘s website I learned that, together with Linda, she’d recently revived the magazine. As designers working across several decades I felt that Ásdís and Linda’s perspective on hand-knitting in Iceland was sure to be incredibly interesting, so I got in touch with them while I was working on Yokes, with hope of including an interview in the book. What with one thing and another (largely my own very tight publication deadlines) we didn’t get a chance to include our conversation, but I’m really happy to be able to bring it to you here instead. For those of you who are unfamiliar with Ásdís and Linda’s work, might I suggest that you nip over to Lopi & Band (you can view the site in English, Danish or Icelandic) and then come right back here to read what they have to say.

————————

KD: Hi Ásdis and Linda! Could you start by telling us when and how you both learned to knit?

Ásdis: I learned to knit at an early age, when I was about 4 years old, with my mother and grandmother. In Iceland children generally learn to knit in school from the age of 8 but my family (mother, grandmother and aunt) are professional textile enthusiasts, so knitting, sewing, spinning and weaving were always present in my childhood.

Linda: I learned knitting techniques in school when I was 8 years old because it was mandatory for girls to learn how to knit.

(four-year-old Ásdís, learning to knit with her mother)

KD: Were the women (and men) in your family members knitters or craftspeople? Do any of your family members knit now?

Ásdis: Yes my mothers family background is farmers and craftspeople. My mother’s mother and sister (born 1898 and 1903) were a deep influence on my childhood with their handcrafts – knitting, sewing, and weaving. My maternal great-grandfather was a farmer and weaver for the farming community in the north of Iceland and his daughters (my grandmother and aunt) worked the wool, had it spun in the local spinning mill and plant-dyed it for futher use). Today I knit as well as my sister and my daughter (who is 12 years old).

Linda: My mother was an art teacher in primary school. She knew how to knit but I only remember one sweater that she knitted when she was ill and had to stay in bed for some time. My two daughters both knit quite a lot. I taught my eldest granddaughter to knit when she was 5 years old and very quickly she was able to knit with fairly complicated techniques such as double stranded and cable patterns. Today she is 13 and has taught her mother to knit, who then has then gone on to teach her friends to knit as well.

KD: Can you tell me about your education and interest in textiles, and how you both came to work in the Icelandic textile industry?

Ásdis: I studied textile art and design at the College of Arts and Crafts in Reykjavík, with a further year of project design focusing on working with Icelandic wool. Since 1991 when I graduated I started working professionally with the medium of hand-knitting. But from when I was in high school, I had hand-knitted sweaters and clothing for myself and family members, so knitting came very naturally to me as a way to express myself. The years around 1990 were difficult for the Icelandic textile industry, the export of wools had greatly decreased due to less demand from the international market. Many factories producing machine woven and machine knitted fabrics as well as carpets went bankrupt, and the machinery was sold abroad or sometimes simply sold for scrap metal. So during the ’90´s it was considered very out of date and unfashionable to work with Icelandic wool as a medium, either as an artist or designer. But in spite of this (indeed, perhaps because of it, as a form of reaction) there was a growth in the local handcrafts industry. Many rural craftspeople and galleries began making items for the tourist and travel industry, and were thankfully supported by government funding. The Handcrafts Association gained more members during this period, and The Crafts and Design Centre was also founded.

So, then I started designing on a regular basis but began as a freelance designer only. At the same time I began working for the Handcrafts Association as general manager of both the Association and its shop. There I worked from 1994-2008, managing the association (which is primarily a voluntary and amateur organisation founded on the goal of preserving old traditional Icelandic handcrafts and techniques and lending them a modern context). After a period of 14 years I was offered the position of manager for the Icelandic Textile Centre where I stayed for 3 years, working on many projects involving textile art and design. During this time I was also president of the Icelandic Textile Guild. Therefore my main work during these years was a managerial and organisational role within the field of Icelandic textiles, generating connections and projects with other Nordic countries. On the side, I worked as a freelance designer, creating small exclusive projects for magazines, private individuals and exhibitions.

Linda: In primrary school we were supposed to knit specific things with specific colours. I didn’t enjoy that, so I always got a bad grade in textile classes. But when I was a teenager in high school, I drew a pattern on grid paper in a maths class and showed it to my textile teacher who allowed me to knit a baby sweater with my pattern, and I haven’t stopped since. I then went on to study textile art and design at the College of Arts and Crafts in Reykjavík. At first I only designed items for my family. A yarn store owner saw a sweater I made from the yarn she had imported and insisted on getting the pattern to publish in a magazine. The woman who started Lopi & Band saw that issue and contacted me and asked me to design/work for her magazine, which I then did for many years to come.

(Ásdis and Linda!)

KD: I think the period when you both worked together in the magazine Lopi & Band – saw some very interesting changes in Icelandic knitting and design. I wonder if you could reflect on how you fee hand-knitting and design shifted in Iceland during this period? And how it has once again changed today, enabling the revival of your wonderful magazine and designs?

Ásdis: There have been highs and lows in the interest for knitting in Iceland. The years from 1980 to 1990 were a general low despite a certain interest in local hand-knitting (as we explained above). The magazine Lopi & Band was in many ways a optimistic project started by a local lady who was interested in knitting. Initially, the magazine was not particularly successful, and went between a number of editors, until it was finally bought by a small printer. The owner of the company hired Linda who quite successfully edited the magazine with mainly her own and some other designs (mine included). We became friends in 1994 when I began designing for her on a regular basis. By that time, the magazine had become quite popular, with some editions even selling out and being reprinted. Despite the flood of fleece materials and synthetic sweaters on the market, there was a sudden revival in hand-knitting. The patterns we produced in Lopi & Band were diverse and colorful, with fresh approaches to traditional sweater design. Unfortunately in 1997 the owner of the printing press died, his company was liquidated, and at that time Lopi & Band ceased production as well.

The revival of hand-knitting in Iceland is due in a large way to the economic crash in early October 2008. One consequence of the feeling of national tension and hopelessness was that that many people turned to knitting. I believe it was a form of self-help and self-sufficiency – a return to something real, in reaction to the artificial nature of the predicament we were in. It was also a way of expressing a certain kind of nationalism, an attachment to things that are distinctively Icelandic. For example an affluent lawyer friend of mine that had not touched her needles since high school, was suddenly maniacally knitting all her Christmas presents in 2008! Many others looked inwards towards our culture and heritage, which has affected so many things in our society since. Today, people are much more active in exploring Iceland, hiking and traveling inside the country than before. Also, textile artists and designers, such as Farmer’s Market and 66North, are using our heritage as inspiration for fashion and design .

From that time there has been a huge revival in knitting. I believe it has panned out a bit now, but is certainly still more apparent than it was pre- 2008 and is hopefully here to stay.

From 2009 on, there has been an increase in the market of knitting patterns and books in Icelandic, many are translated but a large number are Icelandic designs. Unfortunately the quality is in general not very good, as there is no distinction made by publishers between those that are producing designs and have a background in textiles and those that are hobby-ists which in my opinion directly reflects on the quality of the design work. There are just a few designers working in the field of hand-knitting that have such training, but fortunately Istex employed (c. 2000 – 2012) a very good designer (Vedis Jonsdottir) that took responsibility for their knitting patterns and colour palettes so the range of available knitting patterns and shades was at least above average.

We decided to jump in with so many others in 2011, and try our hand at marketing our own knitting magazine with the revival of Lopi & Band. The magazine has been very well received but unfortunately the market is rather small so we can not rely on it as a main source of income. But we do at least have an outlet for our passion for knitting design and have a measure of creative freedom and control over what designs we produce.

(Hringana – a design by Linda)

KD: My particular interest is yoked sweaters, and I’m fascinated in how they have been regarded, designed and marketed in Iceland, and how perceptions of them have changed. How do you think Icelandic perceptions of yoked sweaters have shifted over time?

Ásdis: The Icelandic traditional yoked sweater was designed for the market in the 1950´s. During that time my aforementioned grandmother was working for Íslensk Ull, a wholesale company that was working on promoting Icelandic Woollens. She was one of the individuals that developed and designed hand-knitted items for the commercial market, both for tourists in Iceland, and for Icelanders themselves.

The traditional yoked sweater gained immediate popularity as it has the very direct reference to Nordic patterns and designs as well as being extremely easy to make. When the final stitch is cast off you basically have a finished item. Quite early on, the yoke became a symbol of Icelandic woollen work and was quickly internationally know as such. Over the past few decades, countless catwalk collections have made reference to the Icelandic yoke sweater, either directly or indirectly.

The yoke sweater became one of the most important sales items in the Icelandic Handcrafts Centre from the time it opened in the 1960´s until it closed in 1997. Then, in the late ’90s, following the crash of the woollen market, it became very unfashionable amongst the general public in Iceland. But in recent years it has certainly become much more popular, partly because of some young designers, that have featured it in their collections, with their own modern twist. From the traditional rather bulky Lopapeysa (3 ply Lopi or Alafoss Lopi) yoke sweaters are now made of 2 or 1 ply Lett Lopi or Lopi Light and have become very fashionable among Icelanders of all ages.

In its early years of development in the 1950s, the yokes were mainly designed in natural colors and those shades still remain the most popular. But during the early 2000´s yokes began to appear in many different shades that had been dyed specifically for the Icelandic market and yokes are always popular with tourists in a range of pinks and light blues.

So the yoked sweater remains the most popular ‘Icelandic’ design, and we’ve certainly come across this in our design practice. We are often asked if we will design more of the “traditional” sort of yoke, but we find that the market has plenty of those and we prefer to show the consumer that it is also possible to make sweaters of traditional wool, with traditional colours, but in a variety of patterns and forms.

(Dagrenning – a design by Linda)

KD: Could you tell me more about how you feel the unique Icelandic landscape, with its equally unique history of wool and textiles, inspires you and your work?

Ásdis: The nature and the history of textiles in Iceland do inspire our work to a great extent. The ever-changing weather and the extreme versatility of the landscape offer endless means of inspiration. The exceptional colors of the Icelandic landscape are perhaps the most inspirational of all! Icelandic textile history, and particularly weaving and embroidery patterns, have inspired designs for both of us. Local techniques such as Icelandic intarsia knitting – which is knitted back and forth in garter stitch – has been an inspiration in one of my favorite designs.

(Barðaprjónspeysa – a design by Ásdis)

Icelandic costume history, especially from the middle ages, has inspired me with both techniques and shaping. A exhibition I did played on designs and coloring from that period, the shaping nodded to medieval clothing while the wool was plant dyed either before or after the garment had been knitted up. My design Valkyrja draws on this inspiration.

(Valkyrja – a design by Ásdis)

Linda: When I quit as editor of the magazine Lopi & Band in 1997 I was part of a group that participated in a research project on Icelandic clothing from the period 1750-1850. The costumes we researched are part of the collection of the National museum of Iceland. During that period I made 4 costumes, replicating national costumes from the era. Through this I became interested in the life people lead so long ago. I then studied folklore at the University of Iceland and graduated with a BA degree. Of course the research and my studies appear in my designs to a degree.

(Peysufatapeysa – a design by Linda )

One of the replicas I made was of an old costume called Peysuföt (peysa = sweater, föt = clothing). Traditionally the sweater part of the costume was knitted on 1.5 mm needles and then felted! The sweater I made was a modernized replica of this original, but on 5mm needles. Since then I have used various inspirations such as turf walls and traditional embroidery patterns.

(Turf sweaters – designed by Linda )

Our most famous painter, Kjarval (1885-1972) has also inspired my designs.

(Linda’s Kjarval-inspired sweaters, including Fornar Slóðir )

. . . and I very much enjoy experimenting with shapes and patterns other than those of the traditional yoke.

(Hum – a design by Linda)

KD: What I find most interesting about your design work is how incredibly innovative it is, with beautiful, and sometimes unexpected uses of texture and shaping. I particularly admire your yoke designs – such as Fletta – in which the shaping does not interrupt the pattern, but remains continuous and integral to it. These continuous yokes are one of the real signatures of your work and to my mind are one of the most significant developments in yoke design over the past few decades. Can you tell me more about your development of these beautiful integrated patterns and how they came about?

Ásdis: When I started designing shortly after finishing the College of Arts and Crafts, my background in the handcrafts tradition ispired me to continue working with the yoke concept that had been so characteristic of the Icelandic woollen sweater. I wanted to do yoke patterns that had a different concept – the continuous pattern but not bands of pattern intercepted with single colored rows. The single colored rows have the function of incorporating the decreases in the yoke necessary for the shaping. I wanted to go the more difficult way … incorporating the decreases into the design for the pattern to flow from beginning to end. This means of course a greater challenge in the design with intricate math and drawing for the pattern to be continuous. The Fletta was one of my first designs and probably the most successful so far. I looked to the traditional Icelandic woodcarvings with their flow of latticework for inspiration.

With Fletta (a braid or “intertwining“) a lattice of pattern is on a background of the base colors of the sweater. With another design – Myrarfletta (bog braid) – the lattice itself becomes the multicolored surface for the play of colours (depicting the bright yellow and green mosses in the Icelandic interior growing around the small streams in the desert).

KD: I wonder if you could tell me about one of your favourite yoke designs, and why you feel it is special / important?

Ásdis: Fletta is my favorite design. I think it is one of the best results I had with the lattice work design, simple yet intricate and very eye catching. It offers a variety of possibilities with color combinations which makes it a very fluid design. I have had it made up to suit individuals coloring (often earthy natural colors), also in graphic color combinations and even bright colorful combinations. All seem to work and provide very different effects.

Linda: My favourite yoke design is the one I made from the Kjarval painting Fornar slóðir because it was challenging to capture the mood of the painting and transfer it to a pattern. And also because no one has done it before as far as I know.

KD: Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts, Ásdis and Linda!

You can find out more about Lopi & Band here.

(Stallar – a design by Ásdis)

I love the Stallar sweater, do you know if there’s an English Pattern available anywhere please?

LikeLike

Hi Kate: The ‘turf’ sweaters are beautiful, simple and useful. Do you know where the pattern is published? Thanks.

LikeLike

Hi Kate, I thought you might like to see this icelandic knitting/yoke: https://38.media.tumblr.com/69b54d6b2cea94fc37cf6835296c9ccc/tumblr_na9gbuZQne1s3n41po1_500.jpg

LikeLike

really beautiful!

LikeLike

My book arrived two days ago. I have been reading and enjoying it immensely. Thank you so much for writing it. Love this new interview too!

LikeLike

Fascinating reading! Thanks for sharing this interview :)

LikeLike

Thank you for the interview. I was wondering whether you knew the pattern name and magazine issue number of the sweater in the very first picture (red haired model with braided hair). I did some research on the designer’s website and ravelry but was unsuccessful in finding the pattern…

Thanks

LikeLike

It’s only a printed magazine in Icelandic – I don’t know that they have any plan of making it as a single pattern, or in English.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing, Kate! My favorite is “Stallar” sweater, amazing colors and texture.

LikeLike

So interesting and inspiring!

I was looking at a deck of cards with Breton costumes thus summer and thinking what a great sweater or fashion collection they would make, similarly the costumes and/or traditional crafts here in Switzerland…. hmmm….

LikeLike

Really interesting, thank you. I’ve been thinking the same as spintounwind!

LikeLike

Thank you so muuch for such an interesting post.

I LOVE all three examples of Fletta; where can I purchase the pattern, I just HAVE to knit it! (probably several times!)

LikeLike

You can purchase the Flétta pattern on http://icelandicknitter.com/en/models/fletta/

LikeLike

Love the Hum sweater, would love to purchase that pattern.

LikeLike

Me too! Is it available anywhere?

LikeLike

Thank you! I really enjoy your articles on the craft and the people involved in this craft. And please oh please tell me the pattern for Hringana is available somewhere. I didn’t find it on Lopi & Band website or elsewhere in my first quick search.

LikeLike

Amazing article..of cource well written..love the history..love the passion of the designers to create, and their commitment to their countries traditions…good for you kate to bring this forward for us to see and learn…pat j

LikeLike

Fascinating interview. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you for the interview. I am waiting expectantly for my book which I am sure I am going to love. I always regret not travelling to Iceland. I got as far as the Faro Islands and bought some beautiful wool from there. My friend, who loves Iceland, has been there several times and always brings me back wonderful knitting books. I know, it’s a bit strange for someone who lives on a tropical island in Australia but then if you love knitting it doesn’t matter where you live.

LikeLike

Wonderful and instructional interview! Enjoyed learning about the country and some of their customs, I went to their web site looking for some of the patterns featured in your article and couldn’t find them, Is there some place to order them?

LikeLike

You can find Flétta from Asdis and Peysufatapeysa from Linda on my website icelandicknitter.com : http://icelandicknitter.com/en/models/fletta/ and http://icelandicknitter.com/en/models/fletta/

LikeLike

Oups, I had the Peysufatapeysa link wrong, here it is: http://icelandicknitter.com/en/models/peysufatapeysa/

LikeLike

oooh. Love their stuff! Is there a pattern for that “Valkyrja” tunic somewhere????

LikeLike

What g great post and great innovative designers/knitters. That last picture really caught my eye, adult and child sweaters…and leggings for the wee one. Thank you for all the history, LOVE it!

LikeLike

Your ability to find such great historical references to all the places you visit and all the work you do continue to cheer me on and inspire me. Thanks for such great postings!!

LikeLike

Many thanks for this introduction to two fine designers!

LikeLike

Hello Karen,

Received your book in good order. Very nice knitting. What Dutch song did you sing?

LikeLike