I don’t know about you, but I am extremely excited about Tate Modern’s Sonia Delaunay retrospective, which opens in a couple of months. I’ve long had a thing for Delaunay’s work, but have never had the opportunity to see much of her work in person, particularly her textiles. I wrote an editorial feature about the significance of her work a couple of years ago for the Rowan Magazine, and it seemed a good moment to reproduce it here.

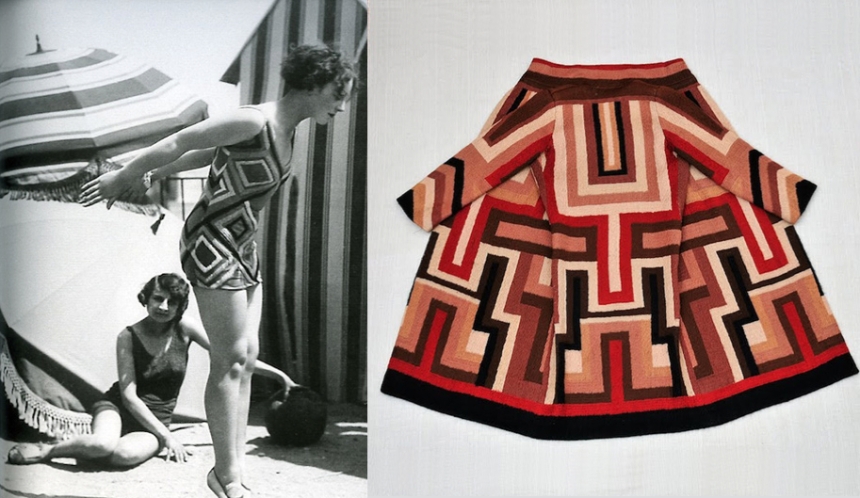

Sonia Delaunay, Swimsuits (1928)

Today, modern art and fashion seem familiarly hand-in-glove. Patricia Field uses the work of Keith Haring to define her version of New York style; Yayoi Kusama collaborates with Louis Vuitton to create novel polka-dotted accessories; Phillip Lim appropriates the art of Roy Lichtenstein to lend his latest collection graphic edge. This contemporary fashion / art symbiosis is at its most obvious — perhaps at its most simple — in Lisa Perry’s recent work. Perry is a fashionable art collector as much as a fashion designer, and in her Madison Avenue store — its bright space-age interior echoing the set-design of Kubrick’s 2001 — you’ll find sharp, neatly-cut shift dresses decorated with the work of Jeff Koons or Ellsworth Kelly. Perry treats the dress as a blank canvas upon which the work of her favourite artists might be showcased. Her work is frequently lauded as “new-mod” or “futuristic” for its minimal lines, its optimism, its bold use of colour, and, of course, for its explicit grandstanding of the works of modern art that she most admires. But Perry’s modernist dress of the future also has a past.

Rewind to 1911. A woman sits in a Paris apartment, stitching a quilt for her son. She selects disparate scraps of cloth, placing blocks and stripes and chevrons of coloured fabric in jarring, daring juxtaposition. The high-contrast result is bold and pleasing to her. She looks around at her apartment, its dark and fussy decoration, its heavy, ornate furniture. Something must be done. Little by little, she embarks upon the radical re-design of the spaces in which she lives. The walls are simply rendered, the furniture is replaced by minimal, modern pieces, and the rooms are gradually transformed into a series of blank planes that seem to wait to be enlivened. The woman continues to cut and stitch, to paint and to embroider. A set of curtains here, a pair of cushions there. Upon the wall, she daubs and hangs a canvas of interlocking discs lit up with incadescence. Turning to her own garb, she adopts loose, unstructured clothing, counteracting her garments’ economy of line with bold, swirling, surface colour. The woman’s world is now awash with dynamic hues and her lived environment — clothes, furnishings, paintings, decorative objects – have all become part of the same wild collage. This woman is Sonia Delaunay, whose distinctive aesthetic and many talents made her central to the development of modernist fashion design.

Born in Ukraine, and educated in St Petersburg, Sonia Stern’s background was privileged, and her education wide-ranging. She excelled in mathematics, needlework and painting, debuting her talents in the latter with a solo show in Paris in 1908. It was in Paris that she met Robert Delaunay — one of the early Cubist group of artists interested in transforming contemporary theories of colour. While Robert’s canvases explored new ways of making colour itself the subject of art, Sonia brought her own sense of colour to life in a perhaps far bolder and more extensive way, moving beyond fine art to household textiles, theatre, poetry, film, print, interior design, commercial illustration and, of course, fashion.

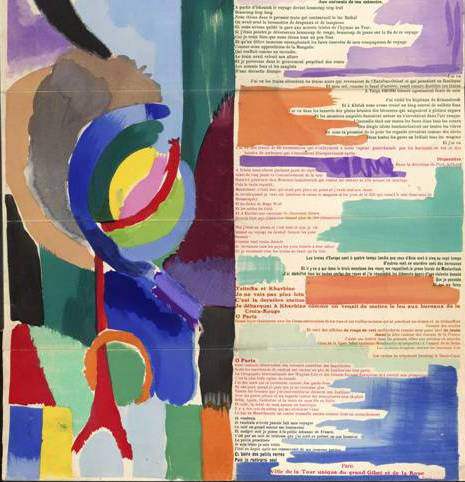

Delaunay’s La Prose du Transsibérien (1913)

Delaunay’s early approach to colour was exemplified in La Prose du Transsibérien, a 1913 collaboration with Swiss poet, Blaise Cendrars. Over the unfolding pages of this spectacular book-object, (published at some considerable expense by Cendrars himself) text and colour were brought together in a unique relationship. Cendrars’ words, and Delaunay’s colours intermingle, collide, wrap around each other. Delaunay was not merely illustrating Cendrars’ text, nor was she developing what might be regarded as a simple dialogue between text and image. Rather, her contribution to La Prose du Transsibérien was to enable colour to become a creative participant in the poetry itself. Delaunay’s rhythmic swirls and splotches produce alternate dissonance and harmony, dynamism and movement, traveling across and around, up and down the page, as Cendrars’ narrator takes an uneasy journey through the conflict and chaos of revolutionary Russia. In the final section, text and image are jointly illuminated with energy as the narrator arrives in Paris, with its bustling streets, new technologies, and iconic constructs — most notably the Eiffel Tower, which announces itself joyously in Delaunay’s brilliant blocks of colour. Each printed copy of La Prose du Transsibérien was contained in a wrapper declaring itself to be “the first simultaneous book,” neither text nor artwork, but an object that demanded to be seen and read at the same time. Cendrars and Delaunay had together painted a picture of words, and written a poetry of colour.

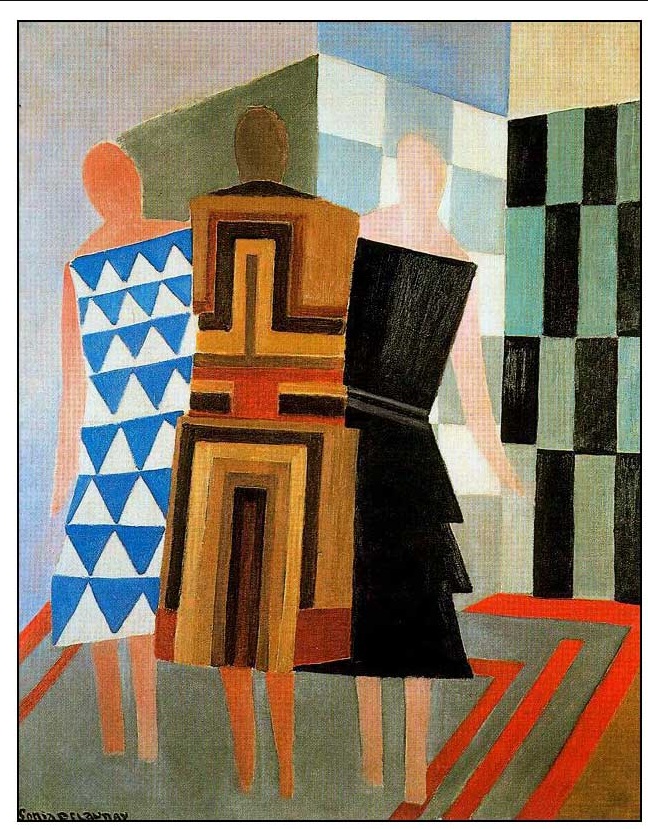

Delaunay Three women dressed simultaneously (1920s)

“Simultaneous” was a word that Delaunay applied to much of her work — paintings, illustrations, printed textiles, and embroideries. The word “simultaneous” referred primarily to her particular take on hue (in which contrasts co-exist, lending images and fabrics movement and multiplicity), but extended beyond this to describe her collaborative and often multidisciplinary methods of working. Delaunay’s exuberant idea of the “simultaneous” meant that she might regard the making of a dress, a dance, a poem, a painting, a hat, a melody, a film, a building or a bookbinding — as part of the same energetic creative process. While other artists of her generation struggled with disciplinary boundaries, she happily ignored the distinctions that were assumed to exist between fine and applied art, or indeed between art, craft, and commercial design. Certainly, her distinctive brio as artist and designer derives from her confident handling of so many different media. “For me” she wrote:

“there was no gap between my painting and what is called my decorative work . . . I never considered the ‘minor arts’ to be artistically frustrating: on the contrary, it was an extension of my art, it showed me new ways while using the same method.”

After the dark days of the First World War (which the Delaunays spent in exile in Portugal and Spain), Paris began to reinvent itself anew as the quintessential modernist city. The world seemed to suddenly spring to life with energy and rhythm: electricity, mass production, jazz. Delaunay’s work chimed with the moment, its new sense of optimism, its dynamism, its bright variety and contrast. She began a series of productive collaborations with like-minded artists in a wide range of fields. She was commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev to create costumes for the Ballets Russes, produced robes poemes with Tristan Tszara, and worked with film makers Rene le Somptier and Marcel L’Herbier on costume and set design. Delaunay developed a particular interest in dance, becoming fascinated by the relationship between the body and the textiles that clothed it. For someone who regarded “colour as the skin of the world” it seemed obvious that dress might become a sort of mobile, dynamic tattoo. Delaunay’s friend Blaise Cendrars, celebrated the effect of her clothing in his famous poem On her Dress she has a Body, and Delaunay herself regarded the wearing of “simultaneous” clothing as a sort of physical performance. She and Robert sported her brilliant simultaneous outfits at Parisian balls and cultural events, attracting considerable attention from their contemporaries. This idea of dress as performative, wearable art, resonated with many modernist movements, including the constructivists, surrealists, and of course the futurists (who made clothing central to their manifestos).

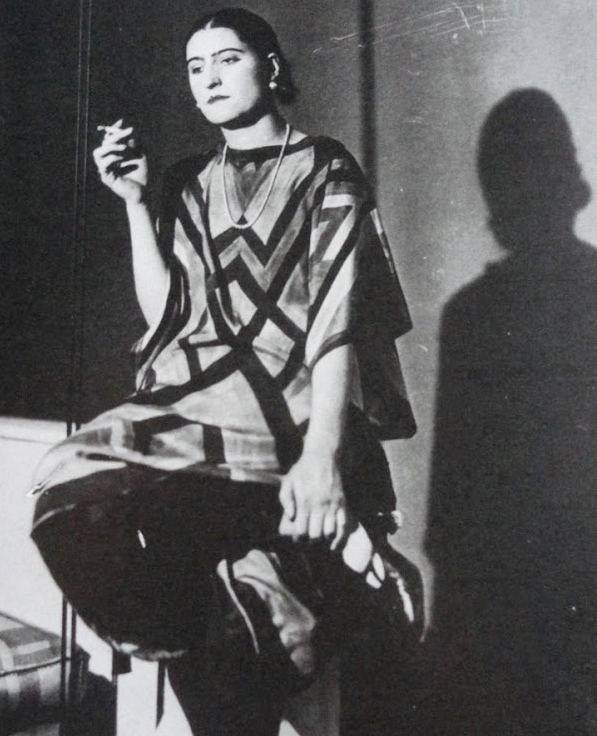

Delaunay, in garments of her own design.

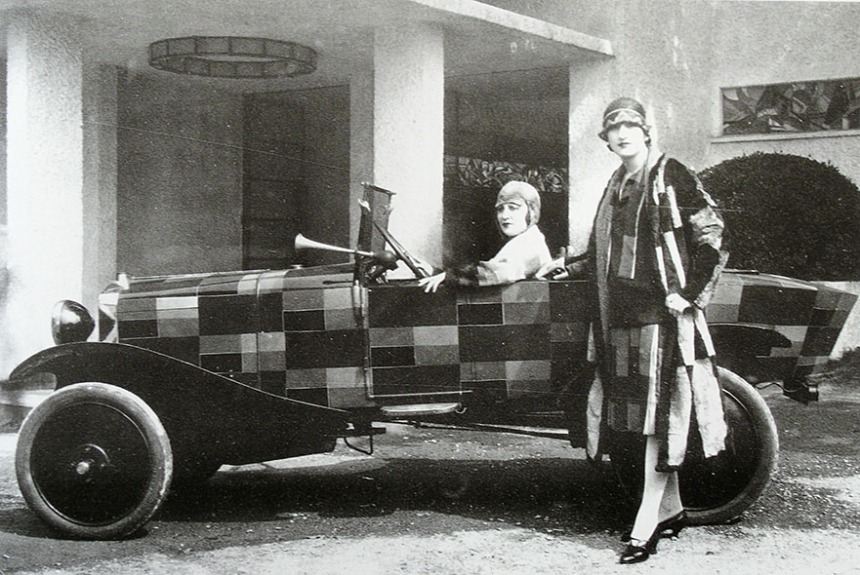

Delaunay began to receive commissions, and swiftly rose to prominence as a commercial textile designer. She was just as confident in the world of fashion as she was in that of fine art, declaring herself incredibly frustrated with the trends that had dominated the 1910s, condemning the hobble skirt (“the skirt is not adapted to walking, but walking to the skirt, which is nonsense”) and what she saw as the pointless “multiplied refinements” of Art Nouveau. Like Chanel, she favoured a total economy of line and garments in which form clearly followed function. “Dress,” wrote Delaunay, “must be adapted to the necessities of daily life, to the movements which it dictates.” Her modern customers were clearly in agreement. In Paris, Baudelaire’s male flaneur had transformed into the female flapper: women were cutting their hair, wearing dresses they could dance in, and adopting the mode garçonne. Delaunay was keen to design modern clothes for modern women, clothes with a purpose and function to the fore. Her simultaneous fashions were meant to move with the body that moved in them. She designed hats to drive in; skirts to dance in; swimsuits to swim in; thick coats and wraps in which to swathe the body during a brisk Winter’s walk. Her bold garments, in which the female body was animated by the colours and rhythms of the modern city, had found their moment, and were the surprise hit of the 1925 Paris exposition.

“How natural it will be,” Robert Delaunay enthused of Sonia’s newly popular designs:

“to see a woman get out of a sleek new car, her appearance answering to the modernised interior of her home, which is also shaking off its old, dusty cornices to rediscover simple, pure lines. [Sonia Delaunay’s simultaneous fashions] are responsive to the painting, to the architecture of modern life, to the bodies of cars, to the beautiful and original forms of airplanes — in short, to the aspirations of this active, modern age which has forged a style intimately related to its incredibly fast and intense life. [Sonia Delaunay] creates fabrics that are oriented to an era yet to come.”

Delaunay suddenly found her talents in great demand, and was celebrated everywhere by fashion writers and cultural commentators as the designer of the “dress of the future.”

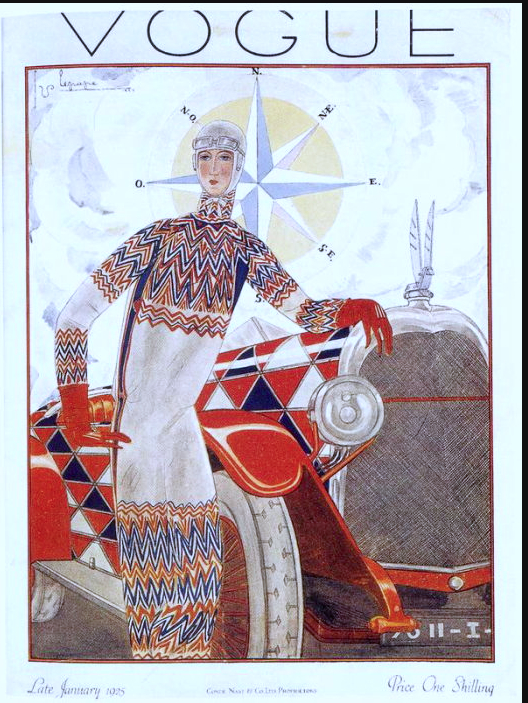

Delaunay’s simultaneous fashions on the cover of Vogue (January, 1925)

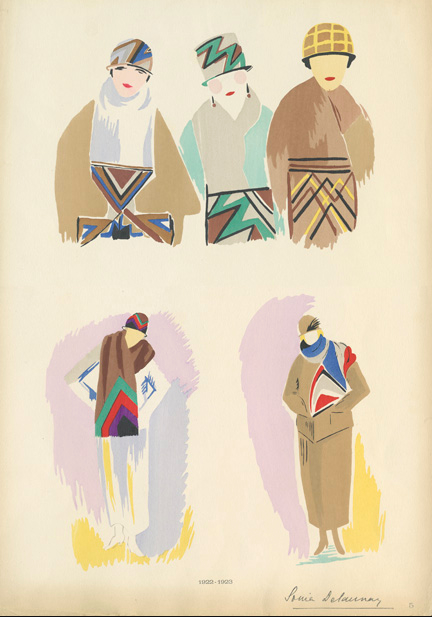

What was it about Delaunay’s simultaneous fashions that made them feel so modern, so very future-oriented, in the 1920s? First, of course, is her particular use of colour. At a first glance, her palettes seem to be almost abandoned, alive with multiple, wild hues, but on closer examination one sees that they are in fact almost minimalist — generally limited to three or four shades plus neutrals. She tends to use vivid contrasts, and a little tonal shading, in signature arrangements of chevrons and swirling discs. In Delaunay’s “simultaneous” outfits, it is these chevrons and zig-zags — sometimes printed, sometimes rendered in dense, embroidered satin stitch — that are key to creating the undulating, almost prismatic effect of movement from her carefully-chosen palettes. Her shapes have rhythm, but they are also freed by a lack of strict regularity (Delaunay often became irritated with those who suggested her designs were ‘geometric’ as she felt this reduced their vitality and individuality to a sort of painting-by-numbers.)

But Delaunay’s simultaneous fashions were also modern, and modernist, in their use of fabric as a plane. Among her contemporaries in couture, her designs were perhaps definitively planar, two-dimensional, in their treatment of material. While other designers (Fortuny; Vionnet) were exploring innovative three-dimensional sculptural techniques of pleating and cutting, Delaunay saw her simply-shaped designs as flat surfaces waiting to be animated by rhythm and colour. (She later described herself as “incapable of sculpting”). The straight-up-and-down shift dress was, then, her ideal blank canvas, and its simple, unobtrusive lines perfectly suited to being transformed by her into a walking work of art. In this sense, her work has much in common with the Bauhaus treatment of planes and surfaces (indeed Walter Gropius was a friend of Delaunay’s, and a great admirer of her interiors).

Swimsuits (1929) Coat (designed for Gloria Swanson) (1923)

Delaunay had her own vision for fashion’s new direction. Designers should not be tempted, she wrote, to take “inspiration derived from the past” but must instead “grapp[le] with the subject as if everything begins anew each day.” The work of artists would achieve popular currency, and be properly valued; collaborations with technologists would make beautiful, quality design accessible, affordable and wearable by all, and through improved mass production, fashion would at last “democratise itself, and this democratisation can only be beneficial since it will raise the general standards of the industry.” “The future of fashion is very clear to me,” she wrote with characteristic confidence.

Beachwear, fabric design, dress (1920s)

Delaunay was speaking, of course, with the familiar optimism of the 1920s. Her perspective (as much as her bold aesthetic) is recognisably modernist in its faith in new technology, its wonder at the potential of mass production, and its belief in a better future. Things appeared rather less bright and hopeful over the next few decades, as the world was shaken by economic collapse, horrific war, and its grim aftermath. Delaunay closed the fashion end of her business, continued to paint, and worked closely with the Amsterdam firm, Metz & Co producing innovative surface designs for textiles. She began to explore the potential of the square, and professed admiration for the work of Piet Mondrian.

Not until the 1960s did Western culture feel an optimism, an energy, a hope for the future comparable with that of the milieu Delaunay had inhabited forty years previously. And how did fashion mark this moment? With a straight up-and-down shift dress whose simple lines were enlivened with a bright and striking work of modern art.

Yves Saint Laurent’s Mondrian dress (1965)

By the late 1950s, mod girls, frustrated with the era’s fashions, began to stitch up their own simple shift dresses — dresses in which they could dance to the rhythms of jazz and soul. Designers such as André Courrèges took their cue from the street — raising hems, and radically simplifying the line with the elimination of bust and waist in a manner obviously reminiscent of the 1920s. The season following the first appearance of Courrèges’ angular mini dresses, Yves Saint Laurent debuted a collection whose show-stopping garment was a shift dress boldy emblazoned with a painting he identified as Piet Mondrian’s number 81. Yves Saint Laurent famously declared himself as “a failed painter,” but like much of his work, this dress was certainly suggestive of aesthetic innovation rather than deficiency. Situated at the intersections of art, fashion, and popular culture, it spoke powerfully to the moment. By 1965, largely because of photographic reproductions, the work of Mondrian was so instantly recognisable that it had become iconic. In a canny move, YSL, in effect appropriated that iconic status for his dress which, when it appeared on the cover of Vogue in 1965, created an international sensation. It was hailed by Harper’s Bazaar as “the dress of tomorrow” and within weeks, printers and cutters were hard at work creating copycat Mondrian shift dresses for everyone, at every price point. The YSL ‘originals’ cost around £1800, and were fashioned from high-quality wool jersey. Each coloured block and line was painstakingly cut and individually stitched to create a bold streamlined patchwork. But by 1966, cotton or rayon dresses featuring a Mondrian-esque design printed directly onto the fabric were circulating on the streets of London for between £37 and £60. Then, in a shift that anticipates some of the complexities of the art-fashion nexus today, the popular currency of the YSL dress began to reflect back on the commercial value of the work that had inspired it. As iconic fashion borrowed from iconic art, so art capitalised on fashion as Mondrian’s work began to circulate for astronomical sums on the US art market.

In a way, YSL’s Mondrian dress achieved Sonia Delaunay’s modernist vision of the popularisation of art, and the democratisation of fashion (though Delaunay would have probably preferred it if this had been accomplished through high-end mass production techniques rather than copies of ever-diminishing quality). The Mondrian dress also carried clear echoes of Delaunay’s work in its sharp cut, its simple lines, its striking use of colour, and, of course, in the treatment of the garment as canvas. In an interview of 1968, Delaunay dismissed YSL’s Mondrian dress as “society entertainment, circus, promotion,” but also grumpily conceded its evident debt to her work “clever people have made hundreds of millions from my idea.” So was Sonia Delaunay, 1920s designer of the colourful, radical “dress of the future,” the first mod? We might certainly remember her vim and originality when contemplating the rather more obvious — some might even say calculated — work of contemporary designers like Lisa Perry.

This piece was first published as an editorial feature in Rowan Magazine 53 (2013)

Further Reading:

Shari Benstock, Women of the Left Bank (1986)

Jacques Demase, Sonia Delaunay: Fashion and Fabrics (1976)

Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas, eds, Fashion and Art (2012)

Matilda McQuaid and Susan Brown, eds, Colour Moves: Art and Fashion by Sonia Delaunay (2011)

Christopher Wilk, ed., Modernism: Designing a New World (2006).

Reblogged this on Breezy Boho and commented:

Beautiful article. So informative! I love reading up on the history of fashion.

LikeLike

Great article.

LikeLike

Interesting article, you have made sense of her cannon of work. I would be interested to know what you thought of the exhibition, how you would compare her talents to Robert’s and if you think the blanket for Charles was groundbreaking.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for this wonderful article on this gifted artist. I am obsessed with her now!

LikeLike

very beautiful

relooking and redecover Sonia Delaunay, I feel most hapiness this evening, thank you for your page.

LikeLike

unmistakable – even in black and white!

http://www.vam.ac.uk/users/node/6568

LikeLike

Just back from visiting the exhibition in Paris, a few days before closure. A magnificent, vibrant flow of colors went though me, pushing the cloudy parisian sky away…

Beyond the sheer beauty and liveliness of her art, what strikes me is the strength of her creative power, which makes no difference between daily life objects and paintings – all are means for self expression and art performance. Also, the boldness and entrepreneurship she developed over the years are very impressive. What a woman!

LikeLike

My daughter has been to Paris this week and visited the Sonia Delaunay exhibition there and really loved it. She has bought the book too. Very excited to see it all at the Tate Modern this year.

Jacqui

LikeLike

Gorgeous post. She was an inspiration and so are you!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the envigorating read. I had to wait a long 24 hours to read it. I teach art history and in my History of Modern Art a year ago one of my students, inspired by Sonia Delauney, designed two dresses. She did an amazing job in a short quarter length class. What was more impressive was the presentation she gave to the class about what she learned about color, line and form as it applies to the body. Sonia’s production over her career has so many could lessons. I wish we had the quote you give from Sonia that her designs were like performance art -lovely. She merged the imposed divide between craft and fine arts with joyous aplomb.

LikeLike

I wanted a Mondrian dress when I was a child and still have a fondness of the shape and design of those dresses. I enjoyed your previous post about Sonia Delaunay. How fortunate to see her work. I look forward to hearing about the exhibit.

LikeLike

My best friend had a Mondrian dress her mother had made (mid 60s). I was so envious of that dress I still remember it. Thanks for this history lesson Kate.

LikeLike

The freaky thing is, when I first looked at the photo titled “simultaneous fabric” – the close up with the car – I thought it was you dressed up!

LikeLike

Sonia Delaunay has long been one of my favourite artists. Your article was a delightful refresher on her life.

LikeLike

Have you read ‘Fashion is Spinach’ by Elizabeth Hawes? Written in the 1940s, I think; there’s fascinating stuff in it about trying to produce good quality ready-to-wear clothes in the USA, as well as accounts of working for knock-off houses in Paris in the 1920s.

LikeLike

that sounds fascinating, Jesse – I’ll look out a copy

LikeLike

ooh I might learn to drive if I could get a Sonia Delaunay decorated car!

LikeLike

LOVE IT! Thank you.

LikeLike

I absolutely love Delaunay’s work, and have been dreaming of knitting a jacket or pullover-jacket with bold colours and graphic lines as an hommage to her.

LikeLike

Thanks a mill for sharing this article :-)

You are certainly a very inspiring and informing designer to follow :-)

LikeLike

Wonderful post. Thank you for sharing your thoughts and insights. Looking forward to the exhibition.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading it, thank you for sharing. I remember when I was just starting to knit, I was fascinated by the opportunities of knitting/crochet to create the fabric itself. Endless possibilities! Ironically I had a dress in my wardrobe that is very similar to YSL’s Modrian dress and I was so inspired to play with the blocks of color in my knitting. I tried my first knitting piece – a dress with color blocking, it turned out horrible. This dress is stuck somewhere in the darkness of a closet, covered in shame and dust. :) But I still feel excited about creating the fabric, playing around with color and texture. There is so much to try and so much to learn!

LikeLike

Fascinating! Although I know the work of Coco Chanel, I had never heard of Delauney. Thank you for sharing this piece.

LikeLike

the exhibition in in Paris for the time being. You just made me regret not going to see it last week end when I was there…

LikeLike

Have also been to the exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne. Came out of there on a cloud and intend to return. The amazing textiles were an unexpected surprise for me as I only knew her as a painter. Not to be missed!

LikeLike

I have seen the exhibit in Paris, it was absolutely beautiful, and a lot of designs and textiles were there to be seen, even her own dresses. You will certainly like it.

LikeLike

It was a remarkable time for women following the first world war, old constraints had been shaken up and birth control increasingly available at least for the educated. It is extraordinary to see clothing designs that embody all these historical changes and that also envisage so much more. Delaunay’s work might be the zeitgeist of this era. What a fascinating read.

LikeLike

I have just seen this exhibition in Paris, and it is even better than I expected: it is very well curated and you will enjoy the fabric section very much I think. She is such a fantastic artist, designer and woman, it is time that her work is shown and praised. I think that seeing the ‘Bal Boulier’ will be one of my highlights of this year..

LikeLike

Thank you for reprinting this! Delaunay’s work has always attracted me. That Vogue cover – inspiration for a knitted handknit yoke dress . . .

LikeLike

Oh, can we anticipate some Delaunay inspired knitwear? please, oh please

LikeLike

I so hope I’m in London for the Delaunay, thank you for this post.

LikeLike

A revelation of colour, though I’m not sure the style is very me, it’s still fascinating textile history and would have been very exotic at the time.

My mother had a Mondrian-style dress when I was about a year old (so yes, 1965/66) and looks very smart on the old photos!

That 1925 Vogue cover looks very knittable…

LikeLike

It’s great to reread this. Such exciting work and use of color. Once again, thanks for sharing!!

LikeLike

Bravo! What A beautifully written and informative feature.

Thank you for sharing…

LikeLike

What’s old is new again! Wish I had saved my Sixties dresses. Thanks again, Kate, for a very interesting history lesson.

LikeLike

Do I see a reference to Delaunay in your Puffins sweater? It certainly has the same lovely graphic quality!

LikeLike

Wish we could see more art in women’s clothing. This is inspiring.

LikeLike

This colorful piece was such a welcome sight after waking to yet another snowy, snowy day in Boston, MA. Thank you for sharing it. Will you be using her design inspiration in the future? I love her scarfs!

Stay Warm

Nina

LikeLike

I didn’t even know she was having a Tate exhibition – I would love to go to that!

LikeLike

What a wonderful piece of writing, I am really energised by this overview. I love the sense of continuity and history in your account as you join the dots between the works of Delaunay, Yves Saint Laurent and Lisa Perry…

HURRAH FOR SONIA DELAUNAY AND HER AMAZEBALLS COLOURS AND STYLE.

LikeLike

This work might inspire a great sweater or shawl. Might we hope you will do one, Kate?

LikeLike

always loved delauney’s use of color and style!

LikeLike

What fun to wake up to this blast of colour! many thanks.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for sharing this. And there´s another reason for visiting London this spring…

LikeLike

Thank you for your excellent synopsis of her work and influences. We are seeing a resurgence of her themes in fashion, knitting and quilting today–what a debt we have for her innovations in line and color. Her attitude toward the symbiosis of fine and applied art has forecast today’s gallery scene.

LikeLike

Always learning from you. Thanks.

LikeLike