As my business has grown over the past few years I have learned a lot about making things locally. Working with Scottish, Irish, and English producers, I’ve made my own books, and yarn, and knitwear. I’ve collaborated with many different types of manufacturers, from printers and spinners to dyers and wool producers. Being able to make things close to home is amazing, and important, and I’ve learned an enormous amount about why this is so.

I now know so much more about traditional skills and practices, and the significance of their embedding in local communities. Through designing and making different products myself, I’ve grown to understand and value creative labour and crafts(wo)manship in a completely different way than I did when such matters were, to me, purely academic. I’ve a much better knowledge of the always complicated economics of manufacturing (making stuff is really difficult, and, if you want to do it properly, expensive) and I’ve a renewed sense of respect for anyone who makes their living designing, making, and selling anything that they believe in. I’ve met many wonderful people, and my business relationships have often spawned friendships that are really important to me. As I’ve made more things, I’ve a more nuanced sense of what can be done, and the impediments to doing it. And, as time has gone on, I’ve also begun to act in an advisory capacity for other local creative enterprises. I’m finding such consultative roles really interesting and rewarding, not least because through that work I’m able to give something back to the manufacturing and business communities which have sustained my company’s own growth. All of these experiences have led me to increasingly reflect on the real meaning and value of making things “locally” or “nationally.”

I genuinely believe that making things “locally” is good, first because having personal knowledge of each link in a supply chain is probably the best way of achieving transparency in it. I think we should all know more about what’s involved in the making the things that we acquire, and — to make an old-fashioned cultural-materialist point — if commodities wear masks which disguise the means of their production, then I am all about taking those masks away. I also feel that, at its best, making things locally can act as a a straightforward way of assuring quality (in raw materials, processes, and finished goods); of valuing and celebrating the skills and jobs that have sustained communities for generations; and of taking forward important issues of sustainability and accountability in areas which range from environmental impact to fair pay.

An idea of the local is important to me, as a manufacturer, for all these reasons; an idea of the national perhaps far less so.

Indeed, there is much about the idea of the national, particularly in the current climate of doing business, that often gives me pause. How do we, as consumers, interpret the union jack when it is emblazoned upon a British product, created by an iconic British brand, whose products are actually produced half a world away from its rainy-weather and posh-boots country stereotype? (To give Hunter’s wellies their due, as a company they are laudably transparent about their supply chain and matters of corporate responsibility)

Equally how much value can there be said to be in a gold union jack emblazoned shepherd’s crook and the claim of “100% British wool” when the product with which it is associated actually contains 20% nylon? (Speaking personally, I find the new British wool licensing scheme perhaps more confusing than reassuring)

What does a British flag suggest and what might it disguise? And if “made in Britain” is meant to convey superior quality or value, what exactly is it that might make something made in Britain essentially better than another something grown in France, spun in Italy, or produced to admirably high ethical standards in Pondicherry or Peru?

We read “made in Britain” as a sign of trust and reassurance, but why should those words suggest that a manufacturer is more trustworthy, more ethical, more reliable, or operates to higher standards than one located elsewhere in the world? Often this is not the case, as I know from experience. Believe me, in the business of British yarn and textiles today there are many manufacturers whose understanding of issues of quality control and accountability range from lamentably basic to completely non-existent. Because of the poor processing and poor quality control of such suppliers, I’ve had stock completely ruined and, on top of significant (five figure) financial losses to my business, have found myself having to deal with the unapologetic behaviour of men who refuse to be held accountable for the damage they have caused. Such experiences have taught me that the ability to do things well, with care, honesty, and mutual respect, is a characteristic of much higher value in a supplier than where they happen to be located.

Perhaps I now have a very different kind of insight into the somewhat desultory methods of some British manufacturers. Perhaps, too, I’ve been forced to reflect on the conflicted ‘nationalist’ meanings of manufacturing and branding because of a spectacularly badly mismanaged experience with a high-profile marketing company and the UK department of International Trade (which I may well write about another time). And, at a historical juncture that seems riven with divisive messages about cultural and racial difference (and superiority), I’m increasingly concerned that too much “great” Britain branding speaks rather to messages of exclusion and division than it does to those notions of sustainability, or transparency with which, as a manufacturer of “British” products, I might feel proud to be associated.

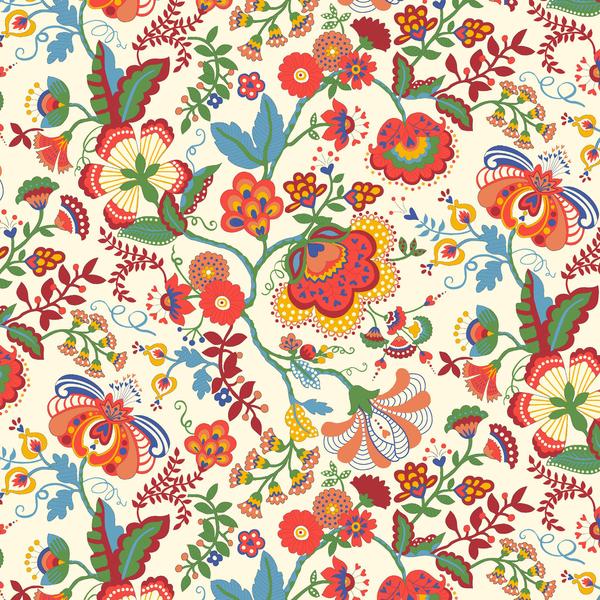

The assumption, for example, that goods made in the far east, or the Indian subcontinent, are inevitably cheap or of poor quality is a misleading falsehood that’s underwritten by our own sense of cultural superiority and the racist legacy of empire. In this country, since the early decades of the nineteenth century, we’ve happily reassured ourselves with the foolish privilege of thinking that textiles made in Britain are somehow better than those made in the countries we colonised and exploited. Yet hidden in such assumptions is the obvious fact that so many products we think of as quintessentially British – from Liberty Tana Lawn, to the aforementioned Hunter boots – are created and produced elsewhere. And at the heart of our tendency toward blithely nationalist branding is a bigger, more uncomfortable truth: that the skills, ethics, and accountable business practices of countless manufacturers elsewhere in the world often leave those of Britain far behind.

(Liberty “Tana” lawn, Indian-inspired design, printed in Italy on cotton grown in Egypt and woven in a range of European locations)

To believe that “made in Britain” means “made better” is parochial and narrow-minded at best, and culturally imperialistic at worst. And if making things “locally” is at its heart about issues of transparency, quality, sustainability and accountability, why on earth should this principle exclude working with skilled communities and manufacturers located elsewhere in the world? I like producing things “locally” because I like to know as much as I can about the materials and processes involved in what I make. I’m interested in local production because I feel it is important for me to be able to see every link in the supply chain, and for me to be able to communicate the story of that chain accurately to my customers. I like producing things locally because I want to work with people who I like and trust, who take pride in what they do, and who treat those who work for them fairly. All of these aspects of local production are important to me – wherever in the world they might occur.

And, as I’ve been thinking about issues of the local and the national, and the the complex matters that can be involved in making supply chains and manufacturing more accountable and transparent, I’ve been working on several different projects. I’m making socks with wonderful yarn spun at a mill close to where I live, which we are having knitted up across the Irish sea, in Donegal. I’m making some fabulous garments with some equally fabulous yarn which, from sheep to finished skein, was produced within a fully traceable 50 mile radius in the north of England. I’ve also produced some project bags with a superb Chennai-based company, whose supply chain ethics and labour practices are of a standard that matches the high quality of the things that they produce. I’ve designed and commissioned some beautiful new lambswool accessories to be produced in a historic mill in the Scottish Borders. All of our books are produced by a printer right here in Glasgow, but we’re also about to produce different kind of print product with a German company, whose manufacturing operation is China based. I’ve been working with a British business I like and trust to develop a top-quality yarn for hand-knitting together with a family-run enterprise in Peru. And I’ve been working with a Yorkshire company to develop another unique yarn combining British and Falkland Island fleeces. All of these projects are “local” in the way that I’ve described and all of the manufacturers and suppliers involved have this in common: they do what they do with genuine thought and care; they are happy to account for where what they makes comes from and exactly how it is made; they treat those who work for them well, and they deal with me, as their customer, with an honesty and respect that’s much appreciated.

There are many knotty and tricky issues involved with manufacturing – waste, sustainability, product miles. I certainly don’t have all the answers. Indeed, I often experience my own internationalism (global digital interconnection is at the heart of what I do) and localism (mine is a small Scottish business, with small Scottish parameters) as a conflict. I love Scotland. I feel very proud to live and work here, and as a designer and manufacturer as much as an (English) Scot, I do feel there is something inherently valuable in working with other nearby producers and in making things, as far as it is possible, close to home. But in an often disturbingly insular and narrow-minded world, I also sense the importance of developing a greatly expanded notion of the local — one that perhaps concerns values and practices more than it does immediate location — an international localism, perhaps, which is able to prioritise some of the ideas I’ve begun to explore in this piece.

All of which is meant as a very roundabout preface to a soon-to-be released new “local” product: yoked sweaters, developed by me, spun and produced from Scottish yarn, in a Scottish mill, into whose stitches have been knitted several generations of history and expertise. I’ll tell you more about these garments in a couple of days time.

I bought the grey and yellow yoked jumper featured in this post. I get so many compliments when I wear it and I am able to tell people you designed it and it was made by Harley of Scotland. As a knitters myself I like to be able to tell people the provenance of my wool and how I made their item.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am rather late commenting, but thank you so much Kate and to everyone else for their comments on this extremely thought provoking and excellently written article. My thoughts have been on these topics for some considerable time, but I could never have put them into words so eloquently.

I despair at the whole mass market ethos in the UK these days; the ‘jingoism’ which has been resurrected (or did it never really go away?) etc. etc., but try to take comfort from the fact that there are many people like yourselves out there who do care.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for writing this, and I hope you will keep exploring this theme! Over the past few years, as these topics have gained greater currency in Knitlandia, I have often thought of your historian’s perspective and your incisive and deeply ethical writing as I was frustrated with a conversation elsewhere — like, “I wish I could teleport Kate Davies into this discussion, I want to know what she’d say!” It has been so fascinating watching you become a manufacturer, and I feel so grateful for what I’ve learned as you’ve shared that journey here.

Lots of passages in the above post had me nodding along, but this most of all:

> “The assumption, for example, that goods made in the far east, or the Indian subcontinent, are inevitably cheap or of poor quality is a misleading falsehood that’s underwritten by our own sense of cultural superiority and the racist legacy of empire.”

My husband’s grandmother was born in China, in the early 1920s, and grew up in New York City. At one point in her life, she was the proprietress of a shop specializing in Chinese decorative arts and antiques. A few precious (and gorgeous!) legacies of that shop still furnish her apartment in the assisted living center where she now lives. When she was more mobile than she is now, she used to enjoy perusing the wares in the center’s jumble shop — I think it took her back to her days as an expert scout of the Tri-State Area’s flea markets and estate sales. She would crow with especial pride when she found some cast-off oddment from a resident who had recently moved in (or recently passed on) that was marked “Made in China”. Of course, we in the younger generations would cringe at this. How could she not know? But then, I started thinking — how could *we* not know? How could we not unpack our unthinking prejudice and ahistorical attitude of superiority? How could we let the banality of the “Made in China” insult colonize our minds?

There’s so much buried in that story, and in all of this — too much for this blog comment! So I’ll stop there and thank you again for everything this blog and your writing is and has been (I think this may be only the second time I’ve ever commented here, but I’ve been reading for just about forever).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Another interesting, thought-provoking and insightful post. I always look forward to your writing and wonder if it is possible to love someone you’ve never met! Thank you Kate.

LikeLike

Kate, your posts are always intelligent, informative and thought provoking. I am especially heartened to know that there are other people like myself who value integrity and ethics. We all need to keep reminding each other that these are important qualities which we need to continue to recognize and appreciate. You are amazing with all the various and different things that you do. You are far more than just a knitwear designer. Thanks for all that you have given me. Susan

LikeLike

I have a shepherdess in Vermont who I recently started following. I even was ble to travel to her farm and meet the well loved flock and buy some of her yarn. I was willing to pay a premium for her yarn since I know it is processed at a mill in Vermont that is over a century old and worth every penny. I have recently bought some of your yarn as well and absolutely loved the Milarrochy Tweed I was impressed by how beautifully it knit up and blocked and would buy from you again in a heartbeat. I remember learning in my MBA class about globalization and competitive advantage. Products were being made all across the globe driven by efficiencies and costs. I choose to support you and Tammy White because I admire what you are doing and to me it is not just about what is the cheapest, but how the animals are treats and the workers as well. People need to be willing to pay more to get the get the products made in the proper way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thankyou, Rosemary. You (and others like you) are what make producers like Tammy and myself keep going.

LikeLike

A very interesting and thought provoking article that deconstructs the notion of “local” and “British made” I’ve long wondered how we can expand the concept of community to be other than a community of localism to a community of interests and your commentary adds to current themes. Well done Kate

LikeLike

Greetings, Kate –

I apologize for asking this here, but I couldn’t find another way to reach you.

You’ve blocked me on twitter, I believe by accident, since in the years I’ve read your blog, bought your patterns, etc., I have never thought or said a negative thing about you. It may seem silly, but it makes me feel sad when I start seeing “tweet is unavailable” on RTs from many fiber-friends on twitter, whenever you’ve published something new.

Thanks for your consideration – I won’t mention it again.

Quinn (@QuinnPiper on twitter)

LikeLike

not sure what has happened here, Quinn – certainly not intentional. I’ll check my twitter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Kate :)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting and insightful read. I have worked retail for years and I certainly understand selling quality items (bikes, skis, outdoor gear). Since becoming a knitter and watching knitting develop and move forward to this more popular trend of “local” I find all of the production fascinating. I want to know where everything comes from and the process from creation to finished good. I want to give credit to all the hands that helped produce an item. All of this cost money. I firmly believe it is time for us all to slow down purchase the quality you can afford and keep all our wants simple! Thanks for the great read and helping to educate us all!

LikeLike

Funny story – I was in Portland, Oregon and (as usual) looking for some souvenir yarn. We stopped at an alpaca farm out in the country that had beautiful, undyed yarn – with the alpacas’ names on it! You could meet them. In talking to the owner, he told me that they send their fleeces to a place in OHIO (where I’m from) for cleaning and processing, then back to Oregon for spinning. So, despite my best efforts, the “local” souvenir yarn had actually traveled as much as me. We are a global society now, whether we like it or not, and I believe that if every person acted as citizens of the Earth first, we would all be so much better off. How do our actions affect all Earth’s inhabitants, not just those in our immediate locale? I think the best we can do is to try to purchase items that are manufactured in a way that protects our environment and those who produce the items no matter where they are from.

LikeLike

As a former Icelandic sheep shepherd, I can speak to this. I was raising Icelandics shortly after Stefania brought them to Canada. Because of the staple length, the only way for me to process my fibre was to send them a considerable distance. Eventually a mill closer to me had “long staple days” but sometimes my fleece waited for a year or more to be processed because there was such demand (long staple days included fibre like alpaca). The processing results, because they were experts at short staple, high grease fibres, varied which is very problematic when you’re selling the fibres. I understand this to have been the case for camelid producers as well. So likely, the mill they used was the one that understands their fibre and gets it done in a timely fashion because I can tell you, it costs a bundle to ship fleece any distance. And, with it remaining in North America, you can be relatively sure that there is less chance of labour and ecological exploitation. That’s part of why California Cloth Foundry and other such companies are keeping their products totally “on shore”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love how makers so often want to get past the surface to truly understand “How is it made?” From a technical standpoint all the way through to the social and economic factors, I really appreciate how you (and others) take away the smooth deceptive mask that covers many of the things we buy.

I have also felt the discouragement and exhaustion from trying to understand all the complexities. But talking about it with other makers (who start to understand the efforts of making something well because of their own physical experience and curiosity) gives me new energy and also the calm assurance that little changes are better than nothing. And although we can’t change everything we can all change something. Thank you for all your work and integrity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

In the late 1960s my birthday treat was to go to London for the day. On one of these trips I bought an alarm clock with a Union Jack face and the popular slogan ‘I’m Backing Britain’ across it in large 60s style black capital letters. It caused considerable amusement when the rest of my family noticed on the train home that the smaller black letters around the edge of the face said ‘made in West Germany’. The more things change, the more they stay the same?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am reminded of how we here in Downunder have almost completely lost our wool industry. Almost all wool grown here is now sent overseas – mostly to China or Turkey, although the very best quality still goes to Japan or, in limited quantities, Europe. One big wool broking company is in trouble in China – not because of any wrong doing but simply because they refused to pay the “extra” being demanded at more than one level. The political situation in Turkey makes doing business there a nightmare.

It would be so much easier to do it all here – but nobody will pay the price that would have to be asked .

LikeLike

So very well put. Clear and precise and experienced. Thank you for bringing up this topic.

It’s a tricky one, isn’t it, because at the end of the day, even locally produced goods often travel the globe.

I am knitting with your wool over here on the continent for example!

You have brought up a question which I have been meaning to ask: Why do you use nylon in your socks?

Cheers!

Jo

LikeLike

The mohair socks we currently sell are designed specifically for heavy-duty walking: nylon is useful in this case to ensure the socks wear and wash well. The socks we are producing later this year are 100% wool, however.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for taking the time to reply.

I understand.

The 100% wool socks shall most certainly land on my feet!

LikeLike

Well and comprehensively put, Kate. Those “significant (five figure) financial losses to my business . . . [and] having to deal with the unapologetic behaviour of men who refuse to be held accountable for the damage they have caused” are tough, aren’t they? Been there, done that, more than once, unfortunately. With no recourse. It does give one a deep appreciation for those who communicate well and do good work, wherever they are.

LikeLike

As in your writings on disability, choices to mother or not, perspectives on personal style in fashion… you have again taken a subject and turned a wide variety of facets to the light. So much appreciated! Wishing you well in the newest business endeavor!

Have you considered setting up a self-guided local supply-chain tour for visitors to your part of Scotland? Maybe an illustrated guidebook that customers could purchase both as a work of art in itself and use as passport for admission to sites where various suppliers might be willing to make some areas available for viewing on specified days/times.

LikeLike

Thoughtful piece that looks at the complex issue from many angles. Thank you.

LikeLike

Great piece. Really made me think, thank you.

LikeLike

Well said indeed- and very timely.

LikeLike

Great piece. I have to know what that sweater pattern is though.

LikeLike

It’s enlightening to read that another country is promoting nationally – made products. I should have realized that it isn’t just a U.S. issue. Tariffs are further complicating the issue. Here in the U.S., where many would like to encourage nationally – made, the primary reason given for outsourcing parts or materials internationally is price. Manufacturers assume they won’t be able to sell a more locally sourced product at a higher price. Certainly price is a factor in basic goods, but what about luxury items? Should it matter if the goal is to avoid the costs and politics of acquiring goods from other nations? Just pay whatever it takes, and feel secure that you aren’t contributing to the negative aspects of global trade. Or do without if your budget prohibits the purchase. Hmm?

In reality, price is a big factor. We operate in a global economy. There’s no going back now.

LikeLike

Extremely well stated, Kate, and very timely.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing about this Kate. I’ve long been thinking about some of the issues you address – cultural imperialism, implicit nationalism – from the perspective of the consumer. There’s a lot of problems with the (implicit) messages that are being send, especially in today’s world were we seem to be living in the absolute daftest time-line possible. I’m glad you’ve also shed some light to a producer’s side on this issue. A lot of problematic aspects that get rather explicit in the “Made in Great Britain”-campaigns are implied in a more subtle ways in more localized versions as well, but in your opening you explained well why the ‘buy local’-ethos does have merit, in the accountability of the supply chain. I’m glad you’ve written a post about this. It’s a complicated issue, so much so that I’m still trying to find out my position in relation to all this, but I do feel our community does well to start discussing this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This gets to the heart of so many complex issues brilliantly. Your knitting popped up in my Instagram feed and I started following you for your lovely designs…and I didn’t expect you to be such a thoughtful and kind (to people, to the environment, to yourself) person.

I read this while calming our 5 day old baby and it not only calmed me (Thank You!) but gave me a lot to think about.

LikeLike

I can see how your experience as a “producer” has brought a much more nuanced perspective to the idea of local production. Thanks for taking the time to explain your thoughts so clearly.

LikeLike

So looking forward to you selling jumpers. Desperate for one.

LikeLike

Very interesting discussion. Looking forward to finding out more about that sweater too

LikeLike

” . . . a greatly expanded notion of the local — one that perhaps concerns values and practices more than it does immediate location” – I’m glad that you’ve put this so well. This is something I’ll be discussing at home here in California and with friends across the country and abroad.

LikeLike

Wonderful thoughtful piece. Thank you!

LikeLike

Kate, I would believe that everything you said really resonates with us fiber folk in the US and I know my small circle in the Midwest is saying “Yay…Thank you for saying this for us!!” With the exception of yarn I’ve purchased from you (Clubs) and Justyna (2 orders of Foula),

most of my wool is my own handspun purchased from shepherdesses that I know or wish I knew. I have pictures of the lovely sheep who provided me with a gorgeous fleece as well as their name and other information. Some are out East, some out West and some here in the Midwest.

I really appreciate all the time you take to research all your information and it saddens me that you were skinned by unscrupulous persons involved in your wool work. I’m really looking forward to more exciting work from your hands!!

LikeLike

Thank you Kate for this well researched and presented paper.

Knowing the provenance of the things I purchase is key

to my life. I look forward to seeing your sweater project.

Kristin Freeman

LikeLike

Miss your natural color hair; love the sweater

LikeLike

well, that’s not me in the photo! You’ll see me (and my hair) with another sweater shortly

LikeLiked by 1 person

The yoked sweater looks beautiful – can’t wait to see more! Some of what you’ve said definitely resonates with me. The ‘Great’ in Britain has become something of a problem recently, when conveying a sense of superiority – rather than just a description of the largest island. The advertising, and indeed many TV programmes over recent years have fed into this.

A definite yes though to understanding provenance, and knowing that methods of production match our values.

LikeLike

Absolutely excellent work, Kate, as ever. Thank you so much.

LikeLike

Kate – a well taken and a well written article on this very important issue. Thought provoking and thoughtful review, which can only further this discussion. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very thoughtful piece, Kate. Thank you.

LikeLike

I agree with everything you said. Things being as they are internationally, this is probably just a marketeers “trouvaille” that they thought would sell better.

LikeLike

I agree with you Kate and also I can sleep at night knowing my yarn from farm to fleece to needle never left the 500 mile and now I have a nearer mill it is less.

Proud to be British but equally proud to make my products by my hands too.

LikeLike

A very good read, Kate. Appreciate the time and effort you have put into this research as well as your own business. That’s a lovely sweater, coming close to the iconic Marius pattern from Norway. <3

LikeLike

So very delighted I saw you did a Ted Talk off to look and bookmark…………..

LikeLike

What about Wales?

LikeLike

Fantastic post. I love that you are unpacking some of these slogans and encouraging critical thinking about these very complicated and important issues. xo

LikeLiked by 3 people

Excellent outline of what is so hard about making and buying locally, buying ethically and paying a fair price for quality and the craftsmanship involved. Glad that you are wrestling with all this as a maker – I try and do the same when buying but it’s not always easy! Keep going…

LikeLiked by 2 people

All great points, but to me the concept of made “locally” verses “globally” goes to a more romantic sense where slight imperfections are understood and accepted (sounds like you, however, as a business person have faced unacceptable local imperfections, so I understand). Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe Kate makes quite clear that the ‘slight imperfections’ were neither slight nor was her concern so much about the quality of the product itself (which clearly wasn’t good) as about the way the manufacturer treated their clear mistake, and dealt with Kate as the client. It’s not so much a business decision, which makes it sound cold and calculated instead of ‘romantic’, but a human decision not to deal with people who don’t treat each other with respect.

LikeLike

There must be a more befitting word for Kate’s concept of “local” here. Peru, no matter how one rationalizes it, is not local. In political circles, the. Description clearly is “globalism.”

LikeLike

It’s about a community of shares interests … not sure that’s at all the same as globalism

LikeLike

What a mind you have… and, the writing skills to share with your audience (me) the values we care about today. Thank you for caring so much.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Too right!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kudos, Ms. Davies. While am I am half a world away in rural Central Oregon in the US your words resonate. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So thoroughly interesting…as always. I’m not a knitter but have longed for a yoke sweater or cardigan so I’m very interested in your new garment venture. Please keep my little voice in the back of your mind…”size 20, big boobs” sending love xxx

LikeLiked by 2 people

GREAT post, Kate! all about things important to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An eloquent presentation of what should be commonly understood but rarely is… bravo Kate!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kate – my admiration for you – your ethic, your sense of purpose, your commitment – knows no bounds. Always looking forward to your next adventure!

Cheers,

Helen

LikeLiked by 2 people