I’ve a long-held fascination with late eighteenth-century hot air balloons and ballooning. In fact, I’ve even knitted an eighteenth-century balloon (in a square of our International Women’s Day blanket, which references the Montgolfier balloon that appears in the final lines of Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s brilliant poem, Washing Day)

My balloon-themed Barbauld blanket square

In the past few weeks, my historic balloon interests have been further piqued during my research about eighteenth-century Glasgow (of which more in a later post). But why on earth would I find eighteenth-century balloons – or more specifically, the balloons and balloonists of 1780s Britain – so intriguing?

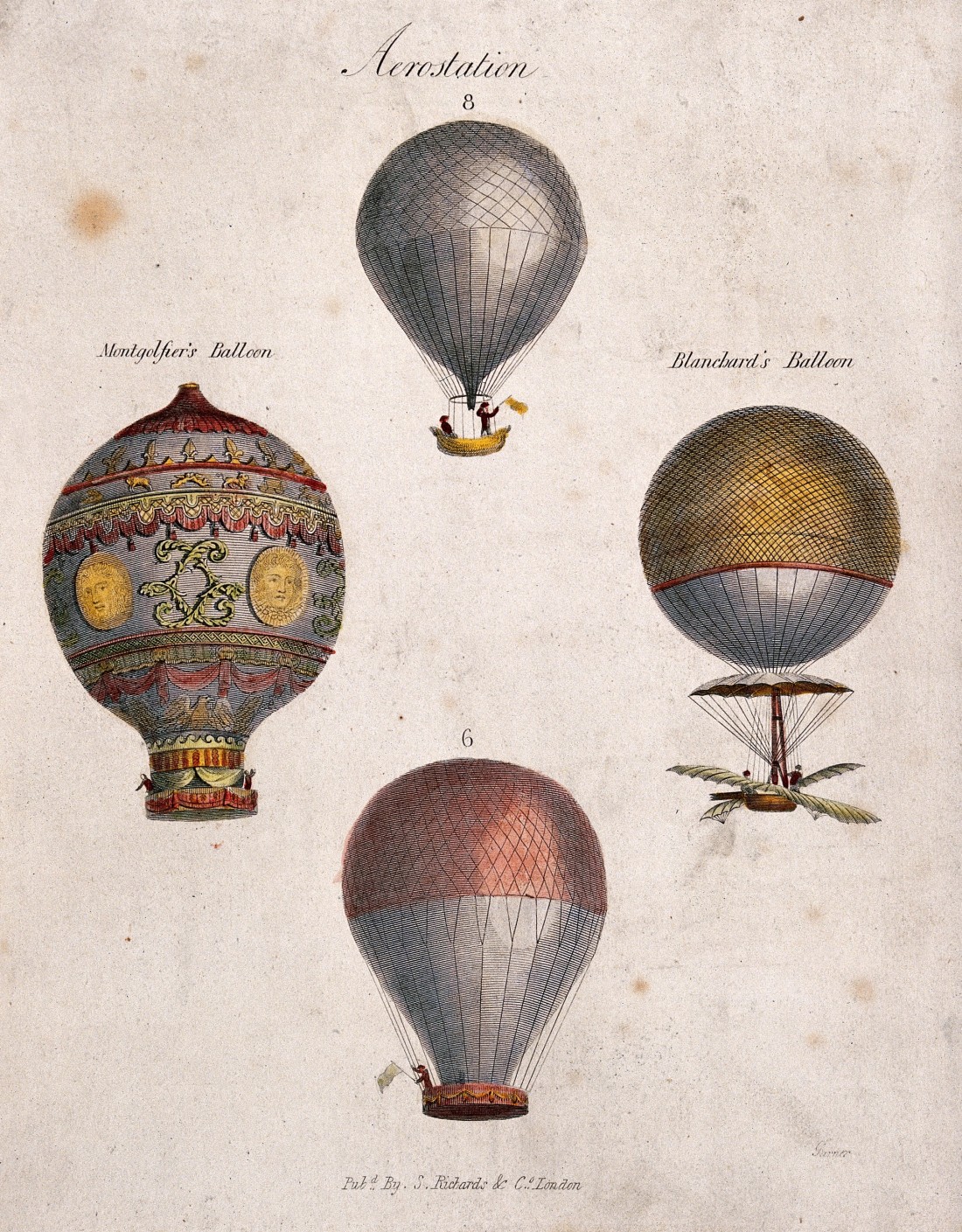

The three years between 1783 and 1786 – which witnessed the first manned (and wo-manned) British balloon flights – were an odd and interesting time. Having just lost the American War of Independence (and with it, the thirteen colonies), questions about British cultural and imperial identity –about what the empire really was or even was for — were pushed to the fore of the national consciousness with urgent debates about the actions of the East India Company and the colonial adminstration of Bengal, which were to culminate in the trial of Warren Hastings. Britain felt confused, tired and deflated. Yet, at the same time that the idea of the nation seemed to be falling apart, stuntmen were inflating gigantic balloons and taking to the air in a series of death-defying – but ultimately pointless – flights that gripped the country.

In the autumn of 1783, as the British evacuated their last positions in American port cities, enterprising paper-makers, the Montgolfier brothers, had begun the first hot air balloon experiments in France, while Swiss chemist, Aimé Argand, flew a small hydrogen balloon from the terrace of Windsor Castle, much to the delight of George III. Suddenly, it seemed, balloons were everywhere, and no one could talk of anything else. “We are all balloon mad,” reported one correspondent to the Morning Chronicle in December 1783, “at every whist party and tea table the conversation turns upon nothing but air balloons.”

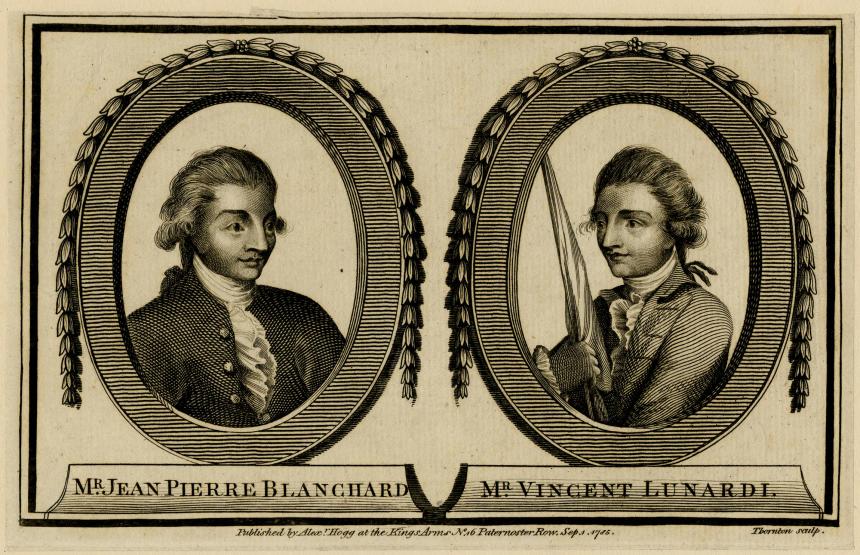

By the following year, Britain was fully in the grip of balloon-o-mania, as The Morning Post reported: “It is fashionable to speak of balloons. My lord speaks of balloons – my lady speaks of balloons – Tommy the footman, and Betty the cook speak of balloons. . . the sprightly miss talks of nothing but inflammable air.” The appeal of balloons to Britain’s “sprightly misses” was significantly enhanced by one Vincent Lunardi, clerk to the Neopolitan ambassador, daredevil showman, and Britain’s first ballooning hearthrob.

Vincent Lunardi by Bartolozzi after Richard Cosway. In this fashionable mezzotint, with his natural hair and fine features, Lunardi is portrayed as a hero of modern sensibility as well as of ballooning.

©The Trustees of the Science Museum

On September 15th, 1784, Lunardi took to the air from the grounds of the Honourable Artillery Company in London, and touched down in Hertfordshire a few hours later.

©The Trustees of the British Museum

Lunardi’s first flight drew huge London crowds, with estimates of those to witness his ascent ranging in contemporary accounts from 150,000 to 300,000. Everyone knew that they’d seen something extraordinary, breathtaking and spectacular, but quite what it represented no-one was really sure. Commentators began to speculate about the science of balloon flight, and its possible utility, but the more they speculated, the less certainty there seemed to be about the purpose of balloons. Samuel Johnson told Hester Thrale that he had no idea “what balloons were for” and, wearied by endlessly enthusiastic accounts of the spectacle of Lunardi’s ascent from his correspondents, suggested to Joshua Reynolds that he could talk about whatever he liked in his letters as long as he did “not write about the balloon.” But it seemed everyone else did want to talk about it: The Gentleman’s Magazine established a special section for “balloon intelligence” and, in the year that followed Lunardi’s first flight, over 180 British balloon ascents were attempted.

Balloons became high fashion. The Prince of Wales appeared at court in a balloon-adorned outfit and fashionable young women could choose a Lunardi garter or a Lunardi bonnet (as memorably noted by Robert Burns’ in his poem, To a Louse)

Balloon ephemera proliferated. The enterprising Lunardi was very canny at marketing himself: he and his balloon rapidly appeared on tokens and medals, snuff boxes and umbrella tops, plates and ribbons.

Pewter medal commemorating Lunardi’s first flight. The Latin inscription translates as: and forthwith the aerial way led to the stars ©Trustees of the British Museum

And if balloons became high fashion, then they, of course were ripe for satire too. Countless ribald prints appeared in which predictable parts of the human anatomy were subject to inflation or deflation

Love in a Balloon. Rambler Magazine, October 1784

If you enjoy eighteenth-century humour, then a lot of these balloon images are certainly very funny. There’s an awful lot you can do, satirically, with an empty vessel and some gas – and that’s precisely why the balloons of the 1780s fascinate me so much.

In early 1780s Britain, balloons are a rich symbol of a particular place, a particular moment wrestling with itself.

The Original balloon An American balloon ascends, accompanied by key figures of the American revolutionary conflict: Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, John the painter, and a two-faced George Washington . In her notes on this print, M. Dorothy George notes that this print is: “the only unfavourable representation of Washington in the collection, and one of the few satires hostile to the Americans.” ©Trustees of the British Museum

What might a balloon represent? A nation whose sense of its imperial self had been so grotesquely over-inflated, that it now failed to recognise the hollow emptiness at its own heart?

A nation whose capacity for theatrical self-delusion knew no bounds?

A nation whose civic culture was now utterly debased by scams, frauds and endemic corruption, but which merely continued to enjoy the spectacular novelty of its own demise?

A nation in whose inflated boosterism was found the recipe for its own self-implosion? whose imminent deflation might be just as extraordinary as its earlier expansion?

In his “English Balloon”, Paul Sandby commemorates John Sheldon and Allen Keegan’s spectacular failed ascent in the autumn of 1784 of a gigantic balloon that was reportedly three times the size of Lunardi’s. The explosion was witnessed by Sandby’s friend, Charles Francis Greville, who produced the mezzotint / aquatint upon which Sandby based his own satiric depiction of the “English balloon” as a gigantic exploding arse, accompanied by an inscription from Horace: ‘In our foolishness, we reach for the sky itself’. Both images ©Trustees of the British Museum

In the balloon ascents of the early 1780s, Britain saw something that seemed simultaneously completely miraculous, and entirely inconsequential. And it saw exactly the same things as it gazed upon itself.

An exact representation of Mr Lunardi’s New balloon. Coloured Mezzotint. ©Trustees of the British Museum

The first balloon flights happened at a moment of particular British cultural uncertainty: a moment in which everyone seemed to be continually striving for some meaning and some clarity, only to discover that all that was out there was a whole load of hot air.

In this attack on the Fox-North coaltion government, (sometimes attributed to Gillray) Charles James Fox, as Milton’s Belial rests atop the inevitably deflating balloon of public faith. The image clearly echoes Fuseli’s famous 1781 Nightmare) ©Trustees of the British Museum

I’m fascinated by the balloons of the 1780s because of what they carry along with them in their extraordinary flights: because of their particular capacity for gathering together all of Britain’s anxieties, blowing them up, and happily popping them like a bubble. I love how balloons can act simultaneously as a celebration and castigation of British popular culture; how they encapsulate the nation’s uncertain sense of itself and the distinctively weird creative energy of a moment in which a man might fly beyond the clouds — to no purpose whatsoever. I love how discussions of balloons can combine faith in human progress with fears of humanity’s imminent collapse or bring together an incipient critique of the eighteenth-century society of the spectacle, with the idea that the spectacle might also be an end in itself. And it is these particular contradictions that I also love so much about the balloon-themed conclusion of Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s Washing Day. I have often thought that her transition between the image of the soap bubble, blown by the bored child on a busy washing day, and Montgolfier’s hot air balloon, moving “buoyant through the clouds” is truly one of the most audacious images in eighteenth-century poetry, which Barbauld, with typical poetic adroitness, also somehow manages to make spectacularly self-deflationary:

sometimes through hollow hole

Of pipe amused we blew, and sent aloft

The floating bubbles; little dreaming then

To see, Montgolfier, thy silken ball

Ride buoyant through the clouds, so near approach

The sports of children and the toils of men.

Earth, air, and sky, and ocean hath its bubbles,

And verse is one of them — this most of all.

I do hope you don’t mind my indulging my eighteenth-century balloon-o-mania, especially as further flights follow in a subsequent post!

If you’d like to read more about eighteenth-century balloons and ballooning, there’s a short chapter in Richard Holmes Age of Wonder (Harper Collins, 2008), or a longer and more thorough discussion written by my old friend Paul Keen in his Literature, Commerce and the Spectacle of Modernity, 1750-1800 (Cambridge University Press, 2012). I’m also indebted to volume 6 of M. Dorothy George’s wonderful Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the British Museum (1938). With the rest of London in 1784, Barbauld paid a shilling to visit Lunardi’s balloon, suspended from the ceiling of the Pantheon, writing to her brother John Aitkin that “the sight of friends excepted. . . nothing, has given us so much pleasure as the balloon.”

Thank you for another interesting article. Kate !

Some of the contemporary images remind me of Brighton Pavilion – the same band of lozenges around the widest part. I wonder if it was a deliberate reference ? I have tried to make a link –

The Royal Pavilion at Brighton, by John Nash

John Nash’s Royal Pavilion at Brighton

View images from this item (2)

LikeLike

I wonder if you know about James Tytler? He was born in Fern , then Forfarshire, now Angus. The son of the minister – he led a very colourful life. He flew in a balloon in Edinburgh a month before the Lunardi flight!

LikeLike

indeed I do – Tytler somewhat overshadowed by the glamorous Lunardi, but his ballooning was just as colourful!

LikeLike

Completely fascinating story of the balloon, thank you for sharing all these finds! As a Pakistani-American, I always knew the British fetishised quite a bit of our culture…but it seems even the hot air balloon advertisements you show here even fall into that category! I, too, have always been fascinated by the balloon. Now I wonder why that is. :D

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Oxford, we had James Sadler too. It seems not many people remembered him. Here is the story.

James Sadler: The Oxford balloon man history forgot http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-28094742

LikeLike

Loved it!

LikeLike

Loved this post, if i could travel back in time it would be so I could watch the Montgolfier brothers first balloon have lift off. I’ve always been fascinated by firsts when it comes to flight and I wish now I had spoken to my nan who was 10 when the Wright brothers made their first flight, I would love to know if she heard about it, what she thought about it, and were people really excited about it. All of these first led to the first moon landings, and I watched then with her, a precious memory. Aside for my love of all things flight related, I really enjoyed the political satire, which I will go back to and I’m sure it will give much food for thought.

LikeLike

I love these posts! Fascinating history, great pictures, a real ‘lift’!

Have you come across the podcast, 99% invisible? A similar eclectic mix of the weird and wonderful.

LikeLike

What an interesting post – it was indeed a very weird time, and quite distinct with the thoughts and actions of those few years.

And yes, there is a definite analogy with what’s going on at the moment. I shall re-read with more time and attention later.

LikeLike

Wow excited to read this!

Our local nursing home in Cupar, Fife is named after Lunardi. He landed the first Scottish balloon flight just outside of Ceres, and there is a little plaque commemorating the occasion there.

He has been a favourite zoom quiz question for us in recent times.

I hadn’t realised he was a “pin up”, I’m now imagining him as blackadder’s Lord Flashheart….

LikeLike

Lord Flashheart is, I think, a very good comparison, Anne Marie!

LikeLike

Thank you, Kate! What a joy to read about these spectacular fin de empire balloons at such a critical stage in British colonial history. I can’t wait for the next in this series,

Emilia

LikeLike

Thank you Kate, this is simply magnificent!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved these images. I, too, find old balloons fascinating (though I don’t necessarily read quite as much into their symbolism). But a fascinating thing, indeed. Andree’s arctic attempt with a hot air balloon is perhaps one of the most amazing (and foolish?) acts of pushing boundaries ever….

Glorious imagery, and astonishing acts of bravado…what a time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely fascinating, Kate. Your interests are so eclectic, beautifully researched and written about. I love not knowing what you will write about next.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely post, as usual. If I may offer another period source for amazing balloon images, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (easily searchable collections on their website) has a collection of 18th century beaded object, made in a very specific technique, called “sablé”. A lot of the sablé beaded purses/boxes/perfume bottles etc have ballooning imaging on them. They are a little known art object, but one I am particularly found of!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love this, Kate – playing right into my fascination with such things ethereal, and my general uneducatedness (up till now) in History beyond Bonnie Prince C. , at which point I dropped History at school (in favour of Music and Biology and Latin and Chemistry, with their own augmentations and proliferations and inflammatories).

I’ve always had a particular distaste for 18th-19th century satire – again up till now. Perhaps I am now ready to let its humour act as a release valve for some of the Hot and Horrid Air of History (and its Causalities and Casualties), which Haunt us to this day.

And in connecting all this to Washing Day … well , here again you have played into my court, my home ground, my internal story … once again you are opening a door into the Magical Land of Dreamscape for my Muse to refresh herself in. I am fascinated by laundries, lavender and la lessive.

Thank you so much. You are quite, quite extraordinary, Kate! May all your hot-air travels bring you safely home x

LikeLike

I love all this new information about early balloons. Last autumn at a history village restored to the 1790s-1840s era, there was an awesome balloon lift, perhaps a balloon too small to carry much of anything. But it was a grand occasion attracting lots of attention. I have a wee video of the event that I cherish.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a very interesting post Kate. I think a simple answer to the fascination is the possibility of escaping gravity, of emulating birds. I suspect that humans have always looked at the soaring and wheeling of birds and envied them. It was pointless with our hindsight but there is a similar fascination for me in the variety of responses to the speed and freedom of the railway- Cranford and Middlemarch! I read somewhere that women were specifically cautioned against going so fast as it would addle their insides and render them barren!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s amazing how eclectic this blog is. I learn so much here. Fascinating, as always! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people