In the Steps of Jane Gaugain

From the quiet restraint of the Regency buildings that line Edinburgh’s George Street, you would never guess that this, a century and a half ago, was the scene of a knitting revolution. Here the ladies of the city gathered to exchange “receipts,” compare their success with the latest stitch patterns, admire vibrant new shades of yarn, or purchase pins, embellishments, and notions. These fashionable and wealthy knitters beat a path to a shop at the street’s West end, where their every knitterly want might be supplied. Here, at number 63 George Street, they found Mrs Jane Gaugain, author, designer and entrepreneur, whose Edinburgh shop was the vanguard of the Victorian knitting revolution.

Born Jane Alison, tailor’s daughter, at the turn of the nineteenth century, Jane married a merchant with property on the edge of Edinburgh’s Old Town. Capitalising on the relaxation of trade after the Napoleonic wars, Jane’s husband imported “Berlin wool, French blond lace,” and “materials for ladies fancy work” to Scotland from the continent. Jane transformed her husband’s shop into a thriving haberdashery, business boomed, and, by the mid 1830s, the couple were able to move to elegant commercial premises on Frederick Street and, later, George Street, at the heart of Edinburgh’s New Town.

Jane was not merely a vendor of goods to the city’s fashionable elite. She was a woman of shrewd business sense and literary ambition. During the decades of the mid-nineteenth century, the culture of knitting underwent a profound change, and Jane Gaugain turned this transformation to profitable advantage. While rural workers in the English North and Scottish Borders still turned out stockings for necessity (and were very poorly paid for doing so), a new generation of wealthy, urban needlewomen had begun to emerge for whom knitting was about luxury and leisure, rather than utility or labour “They have borrowed this fashionable employment,” remarked one Victorian magazine, “from the ladies of Germany,” and indeed, the Saxe-Coburg monarchy, and a royal fondness for Berlin wool, meant that continental knitting was very much a la mode. Edinburgh’s well-to-do knitters were less interested in warm, durable stockings than they were in lacy tippets and elegant muffatees. And, when they came to buy a few ounces of soft, fingering-weight Shetland or Merino from the stylish shop at 63 George Street, they also needed pattern instructions for the delicate shawl for which the yarn was intended. Jane Gaugain was there to provide all of this for them.

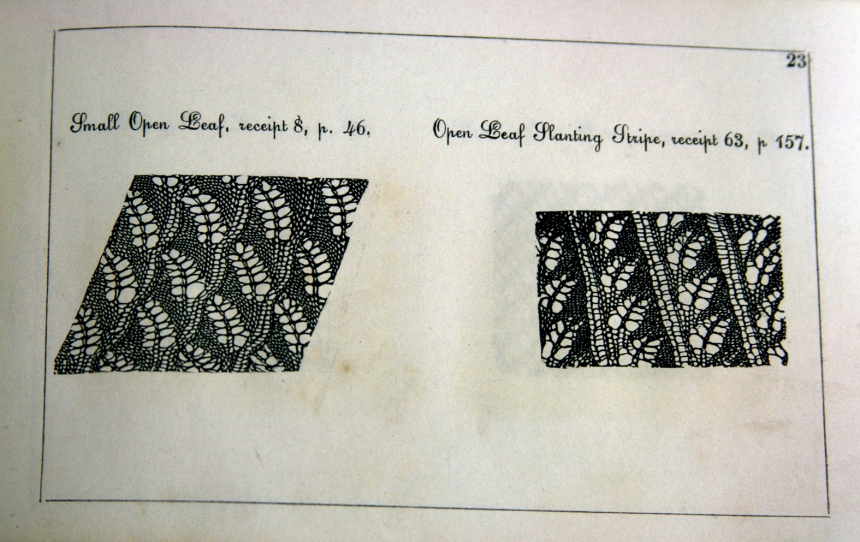

Jane had been writing and circulating patterns on request throughout the 1830s and, in 1840, published the first volume of her Lady’s Assistant in Knitting, Netting, and Crochet to immediate acclaim. The book was conveniently pocket-sized, and the patterns were written using her own unique system of pattern notation—the first to be devised and widely used in Anglo-American knitting until the “K1, P1” abbreviations still in use today. “My method of explaining the receipts, though novel, has been found to answer the purpose completely,” Gaugain wrote, “giving a simple and clear explanation by means of letters and figures, which are easily reduced to practice.” The Lady’s Assistant included patterns for shawls, caps, purses, counterpanes, and a wide range of coloured and open-work designs. The style was crisp, easy to follow, and proved wildly popular. In its first year of publication, the book’s list of eminent subscribers and patrons swelled to several hundred, and was headed by the dowager Queen Adelaide. “It affords me much pleasure,” Gaugain wrote with no small degree of pride in the preface to her fourth edition, “that the reception [the book] has met with has exceeded my most sanguine expectations.”

But not everyone in Edinburgh was excited by the fashionable knitting revolution. Just as Jane Gaugain’s Lady’s Assistant was published, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine declared itself entirely scornful of new books that were:

written solely to instruct ladies in the pretty make believe industry, or elaborate idleness, of knitting all sorts of things in all sorts of crinkum-crankum ways. . . We deny any woman engaged in these knitting processes which must require constant counting of stitches and un-distracted attention, to enjoy her own quiet thoughts. The honeycomb stitch, the ladder stitch, the diamond knitting, the porcupine boa, and the double eyelet knitting are surely enough to drive any woman mad.

But despite Tait’s predictable Victorian suspicion of the effects of complicated knitting on women’s minds, the “madness” for Gaugain’s patterns appeared to be endemic. Throughout the 1840s and 50s, she published numerous additional volumes; updated her shawls to accommodate the “Maltese” and “Swiss” patterns then in vogue; and produced several beautifully illustrated appendices to her Lady’s Assistant. By request, she began to include charted paper and instructions for the enterprising knitter to work out their own designs, and added a mail-order service to her Edinburgh shop to meet demand. “The materials requisite for the various receipts in Mrs G’s works can be forwarded by post to any part of the Kingdom,” one advertisement announced. In Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford (1853), the village ladies (all keen knitters) take advantage of such offers, and are encouraged to buy Shetland wool by post from Edinburgh. Miss Matty and Miss Pole might well have been buying Gaugain’s yarn, and they would almost certainly have seen her Lady’s Assistant. It was the best-selling knitting book of the era, reaching a huge audience on both sides of the Atlantic, and finally running to an impressive twenty-two editions.

Yet despite the immense popularity of Jane’s books, her life was not particularly rosy. Her marriage was evidently unhappy, and by 1851, she and her husband lived apart. Only one of her six children (a daughter) survived to adulthood, and Jane suffered for many years from tuberculosis, from which she finally died in 1860. Coloured by deep private suffering and sad deaths, her story perhaps seems a familiar nineteenth-century one. But far less familiar is the tale of a girl from humble beginnings who built a successful business in Scotland’s first city; who popularised knitting for Edinburgh’s fashionable classes; and whose innovatory method of pattern-writing secured her international renown. Jane’s books remain important documents of Scottish textile history, and continue to inspire contemporary designs—from intricate lace shawls to fabulous knitted pineapples. She is buried in Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery, near to the picturesque waters of Leith, whose steady flow once turned the wheels of the woollen mills that stood beside the river.

Acknowledgments:

Thanks to Ruth Churchman and to Naomi Tarrant, for generously sharing her work on Jane Gaugain.

Edited to add: you can read more about Gaugain in Naomi Tarrant’s recent article: ‘Mrs Jane Gaugain, Edinburgh’s Celebrated Author of Knitting Manuals’ in The Scottish Genealogist, journal of the Scottish Genealogy Society, vol.LXIII, pp3-12, March 2016.

Just glanced at her book. It took a bit to decipher but,after a bit you can see where she is going.I love the Plain ,and Pearl!

So amazing to see how it was done,and how much the words and letters have changed. Very interesting history.

LikeLike

Interesting article. I was interested in the use of the word ‘receipt’ for pattern and why we now use this word, as a keen, albeit amateur, linguist. In Spanish, the word ‘receta’ is used for a knitting pattern (and is the same word for recipe, which I guess a knitting pattern is when you think about it). I first came across Jane Gaugain in Jane Sowerby’s book on Victorian lace a few years back.

LikeLike

Kate, this is just to update the story of Jane Gaugain. I’ve done some more research on her family and it’s published as ‘Mrs Jane Gaugain, Edinburgh’s Celebrated Author of Knitting Manuals’ in The Scottish Genealogist, journal of the Scottish Genealogy Society, vol.LXIII, pp3-12, March 2016. It’s an expanded version of the talk I gave to the Society last October.

Naomi Tarrant

LikeLike

thankyou, Naomi! I will track down a copy immediately and add this information to the post above.

LikeLike

Ah to always learn and enjoy!! thank you for your wonderful perspective on our crinkum crankum avocation!!!!

LikeLike

Wonderful to learn about this woman. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

Thank you so much Kate. I’m obsessed with anything to do with social history and your post was a wonderful read. I had heard of JG (of course) but didn’t know much about her so it was good to have the gaps filled in! xxx

LikeLike

So interesting, and I just had a conversation with a young Italian exchange student who used the pronunciation of “receipt” for a recipe at a dinner at which I met him, and sadly, I corrected him. If only I had seen this first! Thank you always for teaching me something!

LikeLike

This phrase from the Edinburgh Magazine has my mind reeling…”We deny any woman engaged in these knitting processes… to enjoy her own quiet thoughts”. As one still entrenched in an academic environment and the educator of future health care professionals in a predominantly female profession, I am saddened that so many have lost sight of the way the world used to be for women. We have come so far in a relatively short period of time yet our accomplishments can be so easily reversed if the history is lost. Thank you for keeping history alive!

LikeLike

Makes me want to visit there more than ever.

LikeLike

So interesting, Kate-thanks for the information.

LikeLike

What a wonderful post. I’ve knitted for years but never really read much about the history of it. Thank you for your research and writing about the wonderfully addictive hobby. Our LYS in the Midwest USA is run and owned by a beautiful Scot whom teaches us all her love of the craft all while introducing us to many lovely yarns from across the pond.

LikeLike

“Elaborate idleness”, well that’s given me something to think about…

LikeLike

A coffee, and reading your blog on a Saturday morning, perfect!

LikeLike

I watched the study day sessions live while knitting, of course, and your essay is a great follow up. Thank you!

LikeLike

I love how you teach us the history of knitting. I enjoy your beautiful photis that help tell the story as well. You are truly gifted and I for one am so happy you chose this to be your life and allow us to view it!

LikeLike

I just love working in a “crinkum-crankum” way myself. When I’m not knitting and reading at the same time, that is. Too fun! Thanks as always for your great writing, Kate!

LikeLike

Your information is fascinating! I really enjoy your research and pictures of Scotland.

LikeLike

Ah, the ‘madness’ of Gaugain’s patterns. Oh that I would have been knitting when I lived in Edinburgh.

thank you for the history. Edinburgh remains my most favourite city!

LikeLike

Fabulous – thanks for the link to the Shetland videos! I loved the comments about how the real shawls had many patterns in them, many more than the printed patterns from Jane Gaugain and the others. I’ve always loved the Icelandic lace shawl book and have made several of the shawls, but how does one go from following those patterns to creating new ones? With multiple patterns… I’d have to quit my day job. ;)

LikeLike

All this wonderful crinkum-crankum we’re engaged in! Not only is my female brain well-equipped to handle such intricacies, it is those very challenges that keep me sane. Thank you for the glimpse of another age.

LikeLike

Loved, loved this post Kate. So inspiring. The photos make Gaugain’s story come alive for me. I have already watched the lecture on Unst Lace and gobbled it up. I can’t wait to see the other videos this weekend. Thanks so much for sharing this material.

LikeLike

Thank you Kate – I am full of admiration and fondness for Jane and her remarkable story.

How idiotic and dangerous for women the Victorian concentration on female wellness seems today. JG was a heroine, an inspiration and saviour for so very many repressed women. Providing a means of excercising their imagination, intelligence and skill. Vale!

LikeLike

As always your writing is a joy to read. Acedemia’s loss is our gain.

LikeLike

I love that we learn so much from your blog, and from those who also read it and comment. Thank you so much for sharing, long may it continue😀

LikeLike

Free digitized copies of The Lady’s Assistant are available online. The Antique Pattern Library has a PDF version dated 1840 , and the Internet Archive’s Text collection has three volumes of the 1846 edition, downloadable in several e-book formats.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Kate, for the wonderful look back at Jane’s love of receipts & their knitters. (Reading that Edinburgh Magazine review made my mind shout: “Release the crinkum-crankum!” 😊 )

LikeLike

As a linguistic note: I enjoy seeing the use of the word ‘receipt’ to refer to the set of written or charted instructions, since here in Norway they likewise use the word for ‘recipe’ when referring to knitting patterns (‘oppskrifter’). The literal translation of ‘pattern’ is ‘mønster’, which in Norwegian refers to particular motifs and designs that could be used in any number of knitted items (as in Annichen Sibbern Bøhn’s ‘Norske Strikkemønstre’).

LikeLike

Another wonderful, interesting lesson from Kate University. You make the era come alive and make us think. Thank you.

LikeLike

This is why I love your blog!!!! Where else would I have ever learned this info? I think people were so much more clever than we are today. Would I have knit if patterns were not spelled out for me – if I had to do the charting myself? It would have had to be the wealthier folk who would have had the time. Although she worked and raised 6 children. Amazing.

LikeLike

Fascinating, thank you. This is exactly why I so enjoy reading your blogand your books and knitting your designs.

LikeLike

Very interesting – thank you!

LikeLike