(1. Suffragette, chained to railings.)

What a feast of images and words today! As you know, I’m a writer with a background in archival research and women’s history, and today I’ve persuaded fellow writer, and friend of KDD, Michelle Payne, to share some of her own historical research about the British women’s suffrage movement. I’m frequently inspired by the lives and work of these pioneering women – you might remember that I designed a square for Elsie Inglis (founder of the Scottish women’s hospitals) and created my Let Glasgow Flourish Blanket in celebration of the work of local feminist artist and educator, Ann Macbeth. Michelle is (of course) a fellow knitter, and I first learned more about her fascinating work through our Ravelry group – a space where interesting ideas are frequently exchanged! At the moment Michelle is working on a book about the colourful life of militant suffragette and lifelong activist, Lilian Lenton. I’m always intrigued by how writers home in on, and hone down, the focus of their research, and today I’ve persuaded Michelle to tell us a bit more about how she came to be fascinated by the indefatigable and determined Miss Lenton.

(2. Kew arson aftermath. The wreckage of the tea pavilion after Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry’s arson attack in February 1913.)

In 2007 I was an editor in the publishing department of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, working on my first big project, a scholarly account of Kew Gardens’ 250-year history. The book contained a multitude of painstakingly researched historical details, but one, mentioned fleetingly, particularly captured my attention. In February 1913 suffragettes attacked Kew. Twice. On the first occasion an orchid house was smashed and its rare and valuable flowers destroyed. On the second, its tea pavilion was burnt to the ground.

(3. View of Prison to citizenship pageant in the Women’s Coronation Procession, London June 17th, 1911.)

(3. View of Prison to citizenship pageant in the Women’s Coronation Procession, London June 17th, 1911.)

These incidents filled me with questions. The impression of suffragettes I’d gained at school was of well-to-do ladies signing petitions and participating in processions through London dressed in white, holding aloft intricately designed banners. I dimly recalled that suffragettes chained themselves to the railings at Downing Street, and knew some were imprisoned and went on hunger strike – yet even this I somehow imagined to be a passive, suffering form of protest, rather than active rebellion. I had no idea by 1913 the battle for the parliamentary franchise had become so embittered that a small core of activists had resorted to protest through arson and bombs.

(4. Aerial view of the ‘Prison to Citizenship’ pageant in the Women’s Coronation Procession in London.)

Aside from my misconceptions about the movement, and how broad a spectrum of beliefs and views it encompassed, I found the attacks on Kew Gardens personally perplexing. That the beautiful gardens I cherished and walked through almost daily, camera in hand, had been chosen as a site of violent political protest was something difficult to comprehend. Why would suffragettes attack somewhere as benign and tranquil as Kew?

(5. Photographs of militant suffragettes circulated by the Criminal Record Office to police forces and public institutions such as art galleries and museums. Lilian Lenton is number 12. Her photo was taken covertly using a telescopic lens, as she exercised in a prison yard.)

Around this time I read Ali Smith’s novel, Girl Meets Boy. Its opening pages feature a highly imaginative and mythologised retelling of a suffragette’s story, recounted by a grandfather to his two young granddaughters. Ali Smith’s ‘Burning Lily’ is a captivating young woman devoted to the cause. She broke windows, set fire to empty buildings and over and over again slipped through the authorities’ fingers through a series of ingenious escapes. Reading Girl Meets Boy I didn’t question whether the tale of Burning Lily was pure imagination or based on historical fact, I was too busy revelling in the impish, masquerading suffragette who, dressed up as an errand boy and eating an apple, strolled straight past the noses of police-detectives. Historical veracity seemed far from the point. But the book’s acknowledgements explained that the Burning Lily story was adapted from Jill Liddington’s Rebel Girls, a history of some of the youngest votes for women campaigners, so I bought a copy and skipped to the relevant chapters. There I learnt that Smith’s account is largely based on historical record – more importantly, I discovered that Lilian Lenton was the suffragette who reduced Kew’s tea pavilion to ashes.

(6. Linen, lace edged tablecloth created by Winifred Roberts. Emmeline Pankhurst’s signature is embroidered in the the centre, with the signatures of other suffragettes, including Lilian, embroidered in white around the edges.)

A few years later my role at Kew had expanded and I was writing a book about Victorian traveller and artist, Marianne North. In my free time I was studying creative writing and scribbling fictionalised scenes inspired by the fascinating histories in Rebel Girls. I went on to take a Master’s degree, working on a novel featuring a suffragette character inspired by Lilian’s life story. I researched the suffragette movement at large, but for Lilian’s story relied mostly on Liddington’s work and my own imagination.

(7. Detail of Winifred Roberts’ linen tablecloth, showing Lilian’s embroidered signature.)

Eventually, after moving to self-employment, I began more serious research. I started with books and newspapers. Newspaper articles were plentiful, sometimes even featuring Lilian on the front page, but I quickly discovered the classic standard histories of the movement don’t mention her, or do so only in passing. She does not feature in Emmeline Pankhust’s My Own Story. Christabel Pankhurst’s Unshackled gives just one sentence, and that’s an aside. Sylvia Pankhust’s The Suffragette Movement offers a few lines more, mostly in a footnote.

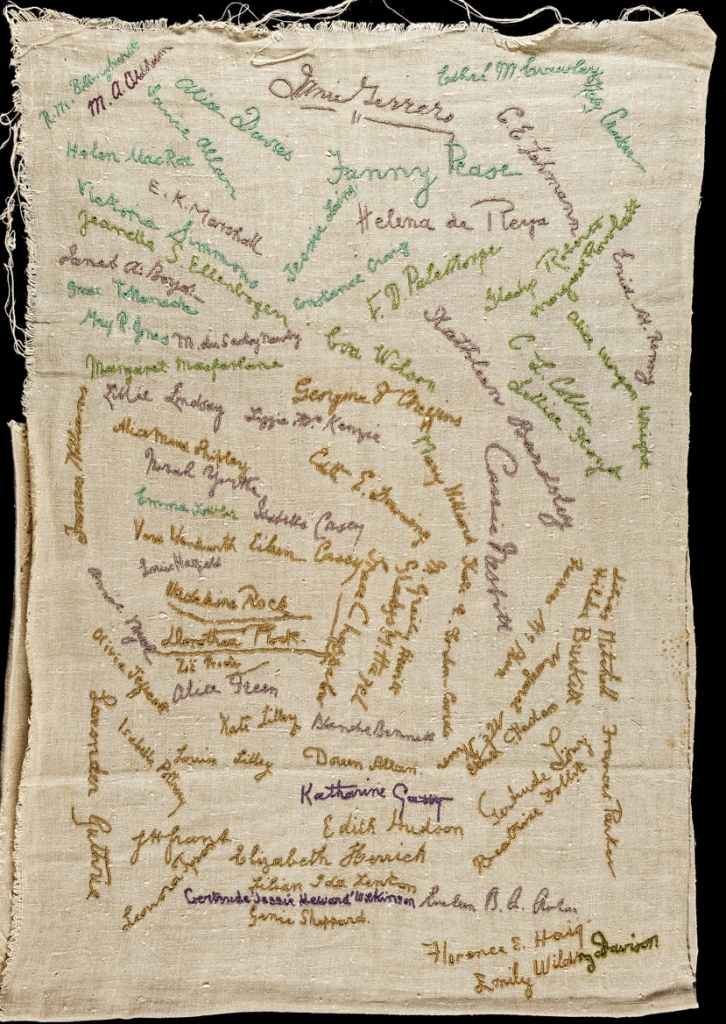

(8. Cloth signed by many suffragettes, including Lilian, while imprisoned in Holloway for window breaking in March 1912. Signed by individuals, over-stitched in purple and green thread by one hand in narrow padded satin stitch.)

I’d heard that nothing brings history alive like archival research, so I turned to this. What I found humbled me. Because – there she was. There was Lilian’s voice, lively and irrepressible while speaking at length in audio interviews. There was her signature, on a linen she and others imprisoned in Holloway in 1912 signed, their signatures later carefully stitched over in purple and green thread. And there was the slant of her hand, in a letter written to a friend in 1968, a revealing account she describes as “a private effort” to describe force feeding, the one thing she despised talking about. Over 50 years later her trauma is perceptible – yet she uses the letter to argue against suffragettes being depicted as suffering martyrs.

(9. Detail of Holloway prisoners’ cloth, showing Lilian’s signature.)

Related pieces of suffrage history, such as the secret prison diaries of Olive Wharry (Lilian’s accomplice in the Kew arson) and Katie Gliddon (imprisoned alongside Lilian in Holloway’s Wing E in 1912), revealed the reality of suffragettes’ prison treatment at this late point of the campaign. In a different vein, reminiscences captured in the mid-1970s for an important oral history of the movement offered fascinating glimpses of Lilian from the varied perspectives of those who knew her at different points in her life.

(10. Katie Gliddon’s drawing of her Holloway cell.)

Lilian’s Home Office files included documents declassified as recently as 2014, and taught me that a document collection, read as one, can be more than the sum of its parts. Piles of internal minutes, prison and medical reports, and correspondences lay bare the authorities attempts to control the narrative surrounding Lilian’s botched force feeding and near death inside Holloway days after the Kew arson, causing ongoing scandal and embarrassment for the government. Notes and handwritten annotations reveal their awareness that Lilian’s humorous and successful escapes damaged the police by exposing them to public ridicule.

(11. Katie Gliddon’s prison diary, secretly kept in the margins of her copy of Shelley’s Poetical Works.)

There is much that isn’t known – and is, in fact, unknowable – when writing from life, but archival objects and materials can be enormously helpful guides. Researching in archives gave me deeper knowledge, and a stronger connection with Lilian, as well as prompting me to reconsider whether a freely fictitious approach was appropriate for my work-in-progress. Whatever the final form my portrayal of her and other less well-known suffragettes takes, I aim to do justice to their complex characters and lives.

(12. The Women’s March, Edinburgh to London, October to November 1912. Mary Lowndes’s banner for Edinburgh, originally designed for the NUWSS procession on 13 June 1908, is seen here.)

Image attributions

2. Library of Congress, Bain collection (out of copyright)

1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. LSE Library, Women’s Library collection (out of copyright)

5. Criminal Record Office bromide print mounted onto identification sheet, 1914 NPG x132847 © National Portrait Gallery, London (use permitted under cc license)

Thanks so much for sharing your work, Michelle! We’ve a lot to talk about – and I’m looking forward to future posts from you!

Hi Michelle! I am way behind on everything but, caught up now on this fine, fine post. I can’t wait to get the book itself. Seems like forever ago that I first read about your desire to write this book and now we are on the eve, so to speak, of its publication. So inspiring! And, I love your new profile pic (also Ravatar).

LikeLike

Thanks so much to everyone who has left a comment – I really appreciate them and have enjoyed reading, replying and ‘liking’!

LikeLike

Hi

There is a recording of Lilian from 1960 in the BBC archive. You can google it. It is a talk she gave about her escapades.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Liam, thanks for this. Yes, I know the recording you’re thinking of. Actually there are two in the BBC archives (or at least there used to be). I took transcriptions plus copies of the links a few years ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s hugely important that these stories are kept alive so that future generations of women understand what others endured so that all women might begin to enjoy equal rights with men. It’s actually not that long ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was quite a tidal wave of information. Things are never what they seem, eh? Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for sharing this!!! I am embarrassed by how little I know about this, and feel especially well suited, given the current situation, to learn more. I really appreciate the included images and captioning, both for the sense of history brought to life that they bring to an excellently told story; and the grace with which they weave in fiber and the way it is used to serve the dual needs of function and art in our lives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am really interested to read this post. My Great Aunt was a Suffragette and went to Holloway Prison on two occasions. One of these was as a result of throwing a brick through a police station window. Her daughter told me that the warders in the prison had been kind to her mother- contrary to what we often hear about imprisonment of Suffragettes.

Thankyou for this posting

Eileen

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

How interesting to have a suffragette in your family! There is one who shares my surname, but so far as I know that’s coincidence rather than a family connection.

I’ve come across quite a lot of first-hand accounts where suffragettes talk positively (sometimes very much so) about individual warders – kindness is actually mentioned fairly frequently. But also lots of harrowing incidents, particularly with prison doctors and warders involved in force feeding.

Prison treatment and conditions is quite a complex area. It varied depending on what prison they were in, and to what division they’d been sentenced. It also varied enormously depending on the year they were imprisoned. In the early years the prison regime was very tough – unless you were of sufficient social standing to be sentenced to the first division (which in itself says a lot about the system back then).

In 1910 a regulation was introduced (Rule 243A, generally known as the ‘Churchill provisions’) which relaxed the conditions of 2nd class imprisonment. It was a kind of compromise between the suffragettes – who always petitioned for the status of political prisoners – and the government who categorised them as criminal prisoners. Its aim was to stop the hunger strike and political prisoner status petitions. Accounts from women sent to Holloway for window smashing in November 1911, when this rule was in operation, show a relaxed prison regime and much mingling between prisoners and warders. But the rule was defined as a privilege granted to prisoners, not a right they were entitled to, so as a way to end the hunger strike it was bound to fail. In March 1912 the rule was withheld from the over 200 women imprisoned for window breaking – and also their sentences were much longer than those given out the previous November. By late April the hunger strike was back, along with force feeding (albeit a fairly short one – a longer and more gruelling one occurred that summer). Looking at accounts from those imprisoned in both November and the following March, you can see how the conditions varied even when only looking at Holloway (although treatment was still more liberal than it’d been for suffragettes imprisoned in the early years). Accounts from 1912 imprisonments also show how much treatment varied by area – i.e. depending on the exact prison the suffragette was held in. Treatment in Holloway at that time was not the same as Aylesbury, which was not the same as in Winson Green and so on.

Treatment also differed when a great number of suffragettes were in prison at the same time, and when they were in prison in small numbers or alone, as tended to be the case with those caught for the more serious offences. Another factor was whether they were in prison on remand (awaiting trial) or to serve their sentence (after trial). So … as I started out saying, it all gets rather complicated and depends greatly on the specific details.

LikeLike

Thank you so much Kate and Michelle for this amazing article! The photos of the Women’s Coronation Procession, the burnt-out Kew Tea House and the Holloway prisoners’ cloth were stunning to see. Lilian Lenton lived until 1972, yet I had never known her name.

Cheers from Galiano.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Looking forward to the book!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Will the book be published by you?

LikeLike

So interesting, thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really looking forward to the book. As someone else wrote especially the reasons behind the attacks (were those places known to be male dominated/ men only etc.?).

(Already tried to still my thirst by reading a bit more on the internet, but it‘s not the same 😉)

LikeLiked by 2 people

It wasn’t that Kew was seen as male-dominated (although, like other public institutions, it was); it was more that Kew was seen as a function of the state and government. (The land belongs to the Crown, but responsibility for its funding and running transferred from the royals to government in 1840). Although private property was damaged from 1912 onwards, it was really the government who they saw as their opponent, and so Kew would have been considered a legitimate target in that sense.

I think there are other likely contributory factors. They wanted to attract maximum publicity – attacking a cherished and famous public garden would certainly do that. With the fire, they wanted somewhere they knew would be empty – it was burnt while closed for winter and at night. They also would have wanted something easy to burn – and the tea pavilion was a wooden structure. The successful (in that no one got caught) attack on the orchid house a couple of weeks earlier may also have been a factor in choosing Kew as an arson target.

Other refreshment pavilions – in Regents Park, for example – were also targeted but generated very little press compared with the Kew fire, perhaps because their locations weren’t as high-profile as Kew, but I suspect also in no small part because no one was caught.

LikeLike

That was superb, fascinating food for thought. So very much appreciate this dip into our history. Thank you Kate and Michelle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to reading your insights each morning. I have more leisure to ponder these days. I’m struck by how much we owe to those brave women of the past.

Luckily, I can ponder and knit!

LikeLiked by 1 person

After some pretty difficult times early this year, I have been working with a counsellor who has been reminding me of the importance of “pondering”: in all sorts of circumstances. It’s a great word and a great thing to do, especially when knitting!

LikeLike

although i condemn all terroristic attackes as burning a teahouse or destroying a greenhouse, it is interesting and important to recall what really happened by whome, and what for, and why she did this.

if this historical research leads to a book, i will probably buy it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is important history. It’s also sometimes, particularly in non-scholarly contexts, misleadingly over-simplified or told in ways that focus more on sensationalism rather than the myriad of factors that influenced the escalation of militant action within the WSPU.

Black Friday (in November 1910) and Churchill’s subsequent refusal of an enquiry into police brutality was one turning point. Over and over again suffragettes cite that day as the cause for their increased anger, frustration and feeling of being engaged in a ‘battle’ against an intransigent state. A truce held for much of 1911 while a Bill (the Conciliation Bill) passed through parliament. When it stalled and failed the window breaking of November 1911, and mass window breaking March 1912, followed. In my opinion, if Black Friday hadn’t have happened, these escalations and the greater property damage of 1913/14 may never have happened either.

A later turning point was the government’s shock decision, in January 1913, to withdraw at the last minute a Franchise Bill that was, with good reason, widely anticipated would be amended to include provision for women’s suffrage. This was when the arsons and other serious damage to property really started (there had been a few isolated instances the previous year but these were individual acts rather than WSPU policy).

These destructive types of militancy (opposed to the original forms of militancy such as asking difficult questions and/or interrupting political meetings, and marching to parliament) were always extremely divisive even within the WSPU. The Union’s joint leaders (the Pethick-Lawrences) were expelled in the autumn1912 because they disagreed with Christabel Pankhurst’s policy of increased attacks on property. Sylvia Pankhurst and her union also split from the WSPU later on, for the same reasons. And many individual supporters of the WSPU did not support the attacks. The exact number of women actively involved in arson and other serious crimes isn’t known for certain, but is thought to be small.

There were also countless suffrage supporters outside of the WSPU who supported the cause of votes for women but did not support militancy. The WFL, for example, supported only non-violent forms of protest such as refusing to pay taxes and the 1911 census boycott, while the NUWSS opposed all forms of direct protest and relied solely on peaceful, non-confrontational, and constitutional methods of agitating for the vote.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the absolutely fascinating info you are giving us, I’m looking forward to the book being published. As an Aussie I’m especially proud of our record in granting women the vote. I am a whole lot less proud in our record of universal suffrage: our First Nations people were only able to vote in 1962. A shameful part of our history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This post was absolutely fascinating. I loved learning about Lilian Lenton and hearing about the research and discovery process.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That was really interesting. I’d love to know the reasoning behind the attacks on Kew Gardens!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! I’ve just posted a few of my thoughts on why Kew was targeted in reply to Stef’s comment – a bit further up the page.

LikeLike

Fascinating essay, and wonderful photographs. Thanks for giving us an insight into your work Michelle. (I can’t wait to read your book!)

LikeLiked by 2 people

This has been totally fascinating , thank you for this insight into a history we very rarely hear .

LikeLiked by 2 people